Current Situation

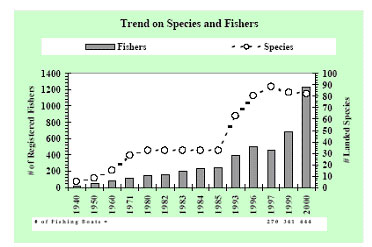

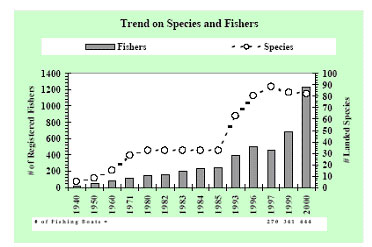

Fishing activities contribute 8% of Galapagos' GDP (Taylor et al, 2002*) and represent the second most important economic activity following tourism (Bensted-Smith, 2002*). The number of registered fishermen on the Islands has increased over the years from 156 in 1971 to 956 in 2002.

More fishermen are however monitored than are registered with fishing cooperatives; for example in the case of lobster fisheries, 1183 fishermen were monitored during the 2000 fishing period compared to the 682 fishermen registered. This indicates a problem of illegal fishing whose cause lies mainly in the lucrative trade possibilities of some target species such as the sea cucumber. The fishing population is diverse and includes long-term local fishermen, part-time fishermen, and short term migrants from the mainland with no interest in the long-term health of the fishery.

The current key risks of the Galapagos fisheries are summarized as overexploitation of sea cucumbers and lobster, danger of industrial fishing in deep water (pelagic fishing), and illegal shark fishing and by-catch

Longlining is also a major concern because of its effect on birds, sharks and related species, and mammals.

Though the current laws and policy governing the Galapagos Islands provide adequate protection of the environment on paper, actual protection of Galapagos biodiversity has yet to fully materialize.

The current laws establish protections full of loopholes. Several problems exist, including the fact that many marine populations (sea cucumbers, mussels, etc.) are sedentary and are easily caught en masse without high-tech fishing methods. Companies are circumventing the law by hiring locals to use semi-industrious fishing methods. In addition, pelagic and illegal fishing are still problems. Artisanal fishing still allows for large boats (up to 60 feet long).

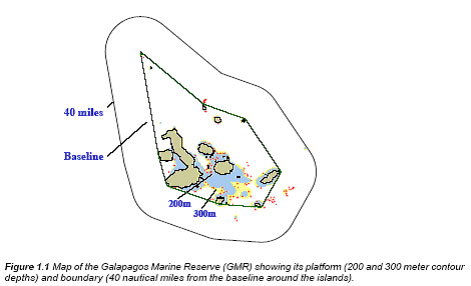

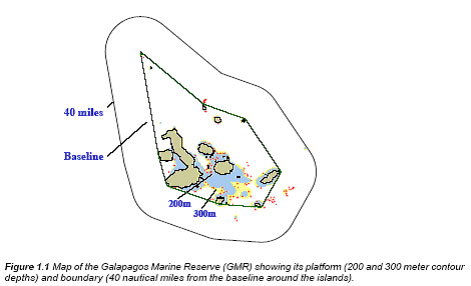

Diagram of the 40 mile zone where industrial fishing is prohibited

(CDF/WWF 2003)

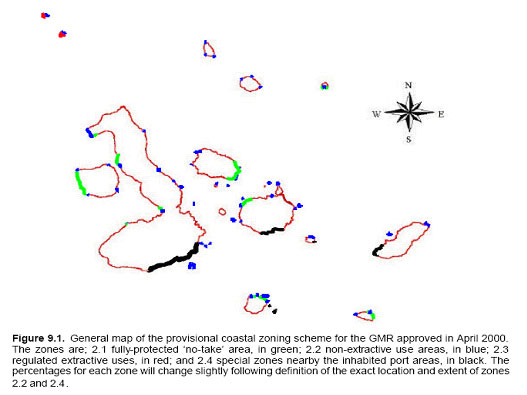

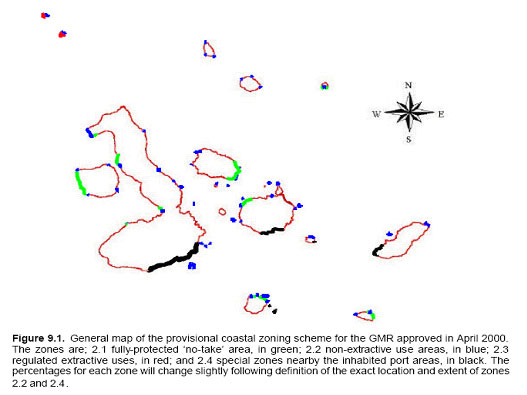

Diagram of current zones of protection around the islands.

[G=no take;B=non-extractive use;R=regulated extraction; Bk=port zones.]

(Charles Darwin Foundation/World Wildlife Fund 2003)

A lack of prosecution for fishing violations has been prevalent. For example, in the 2002 Dolphin death case, over 70 dead and injured dolphins were discovered in the nets of a ship fishing illegally in the GMR. The captain of the boat was only fined 4 cents and 4 weeks in "jail", which was aboard his own boat. In addition, Magdelena, a commercial fishing boat, was captured by personnel from the Galapagos National Park Service in March, 1997. The boat was carrying 40,000 processed sea cucumbers illegally harvested within the archipelago's marine biological reserve. The judge ordered the release of the Magdelena on “transparently spurious” grounds.

Another noted problem is the lack of enforcement, which is mainly due to a lack of funding. In 1999, there was only one ship patrolling the reserve. In 2001, this number had increased to eight ships to patrol the whole of the GMR. In addition, there are many local accounts of easy circumvention. Despite the restrictions against such practices, shark-finning and long-lining remain prevalent.

“Even with proper enforcement, the marine reserve wouldn't be home free. The powerful continental fishing interests are implacable foes of the law, and are certain to challenge it in court. And judges can be bought to delay, obfuscate and frustrate the intent of the law when and if it is applied.”(Butler ’99. Ottawa Citizen)

Also common is circumvention of the law by foreign vessels paying “middle men” from the local population to do the fishing within the Reserve. Fisheries in Galápagos are presently in a totally chaotic situation. The marine area of Galápagos is under assault from three types of fishing.

- First, large international fishing vessels, mostly from Asiatic countries, are fishing around the Galápagos in pelagic zones, and often inside the GMRR. Most of this fishing is illegal and involves devastating, modern, high-technology methods such as large seines and long-lining.

- Second, some modern ships from the Ecuadorian mainland and foreign ships (mainly Asian) with Ecuadorian permissions and/or flying the Ecuadorian flag are also fishing both pelagically and nearer to shore. This fishing is legal, but there are reasons to question to what extent they obey the rules laid down by Ecuadorian fisheries laws and regulations.

- Third, with increased migration to Galápagos, one of the fallouts has been growing interest from mainland Ecuadorian fishing companies and middlemen buyers in what resources could be extracted and sold on the international market. This has been fueled by Asian markets for many of these products as well as capital from those countries. These interests have moved into Galápagos from the mainland and are using the local traditional fisherman of Galápagos as their labor source, and loaning them money or arranging bank loans to purchase boats and equipment. The local fishermen are abandoning their traditional fisheries in favor of these new short-term, rapid economic gain, export product ones. Likewise, these lucrative operations are causing a rapid influx of poor fishermen from the mainland of Ecuador as new migrants. (From Article excerpt by MacFarland and Cifuentes ’96)

The constant “flip-flop” of park directors precludes anything from getting done. The fishermen demand someone new, and then they get someone new. However, park rangers and environmentalists demand someone new. For example, the GNP has had 9 park directors since 2001. This type of shaky government lacks a stable political framework.

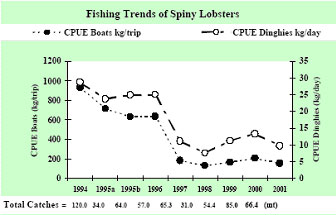

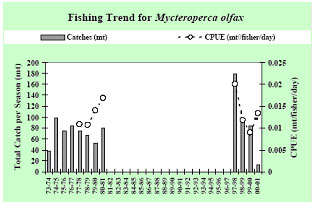

Current trends in overfishing and species extinction portend looming disaster for the Galapagos and its inhabitants. Fishing stocks are on decline.

Fish and Fisher Population Trends

More species targeted with increasing number of fishers

Even More species targeted with increasing number of fishers

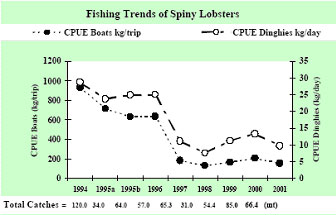

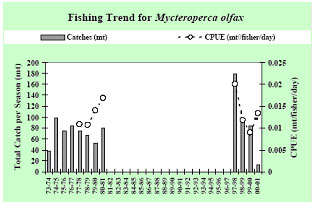

CPUE (Catch per unit effort) is decreasing substantially despite increase in fishing technology. This may be a good thing; as returns from fishing decrease, there may be a decrease in the influx of fisherman. However, this overall trend also indicates dropping fish populations, and if the CPUE gets too low, the fishing of these species may become unsustainable.

Dealing with fishermen and rangers is a delicate balancing act, getting ever more explosive as the tension rises from inconsistency of government decision making. For example, some news headlines have been “Galapagos park rangers walk off job: Tension rises between environmentalists and tour operators” National Post (f/k/a The Financial Post) (Canada)September 15, 2004 and “Fishermen attack protesting park rangers on Galapagos Islands”. The Associated Press. September 22, 2004.

[top]

PSSA Designation

The pressing problem with overfishing and illegal fishing demands that the commission makes it a priority to push the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to officially designate the Galapagos Islands as a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA). As defined by the IMO, a PSSA is "an area that needs special protection through action by IMO because of its significance for recognized ecological, socioeconomic, or scientific reasons and because it may be vulnerable to damage by international shipping activities" (IMO, 2001) In order for the area to be identified as a PSSA, it must meet one of the criteria listed in section 4 of the Guidelines for the Identification and Designation of Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas. The designation of PSSA enables the adoption of associated protection measures by the IMO for the area, including:

- designation of an area as a Special Area under Annexes I, II or V, or a SOx emission

control area under Annex VI of MARPOL 73/78, or application of special discharge

restrictions to vessels operating in a PSSA;

- adoption of ships’ routing and reporting systems near or in the area, under the

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and in accordance with

the General Provisions on Ships’ Routing and the Guidelines and Criteria for Ship

Reporting Systems. For example, a PSSA may be designated as an area to be avoided or

it may be protected by other ships' routing or reporting systems;

- development and adoption of other measures aimed at protecting specific sea areas

against environmental damage from ships, such as compulsory pilotage schemes or vessel

traffic management systems.

Recently, the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) has approved in principle the designation of the Galapagos Archipelago as a PSSA, and it is urgent that proposed associated protective measures be submitted within two years of the approval time. It is worth noting that, given how the prevailing currents around the Galapagos carries any pollution southward to the islands, particular care must be taken to ensure that these protective measures concentrates on protecting the preserve from shipping in areas north of the islands.

[top]

Administration/Institutions

Three bodies can be identified as being directly responsible for fisheries management

- The Interinstitutional Management Authority (Autoridad Interinstitutional de Manejo, AIM);

- Committee of Participation Management (Junta de Manejo Participativa, JMP);

- Four fishing cooperatives with a single representative at the AIM

The role of the AIM is mainly to establish a Conservation Management and Sustainable Use Plan for the GMRR which is coordinated by the Galapagos National Park Service (GNPS) and must be submitted to the Galapagos National Institute (INGALA) council for approval. This plan defines permitted and prohibited activities as well as details of fishing regulations (fishing calendar, amounts, sizes, species, and forms of allowable fishing) within the GMRR.

The AIM also authorizes scientific research on the improvement of policies for conservation and marine fishing development. It includes representatives from the government, research community, tourism and fishing sectors plus a representative of the four fishing cooperatives and operates by majority vote.

The JMP organizes participatory processes; local decisions are made by consensus and sent to the AIM for final ruling. This is in an attempt to involve local fishermen in management.

Membership in the cooperatives is compulsory for all fishermen, as the cooperatives act as their formal representatives. They are primarily political bodies, and in principle could create their own regulations that would apply to all members (for example, limiting who gets quotas for sea cucumbers and boats). The cooperatives are however not strongly organized and show little or no organized cooperation between themselves despite their overlapping interests. Their leaders may recognize the need to coordinate and cooperate but their members do not necessarily strongly support and trust them.

[top]

Possible Solutions for Fisheries

Strengthen cooperatives by: Reducing the number of members or creating preferential treatment for active fishers; Continuing capacity building in cooperatives

Evaluation of this solution:

This addresses the need to limit the numbers of fishermen rather than boats or catch (as will be seen below) but also that to improve the control and definition of the group of people interested in fisheries.

Once the group of fishermen is clearly defined, cooperatives will have an increasing ability to self-organize, represent their interests and regulate themselves. Also, once the group of fishermen is clearly defined, some flexibility can be introduced to allow entry and exit of fishers.

The Special Law has taken a step towards this need already by requiring that all fishermen are members of cooperatives, and instituting a moratorium on entry to cooperatives. Regulations also currently require that artisan fishing permits be granted to residents of the Islands only (GNPS, 1998) but this apparently is not being strongly enforced. Complete lists of members are not fully established and a lot of illegal fishing still occurs.

Explore possibility of creating an Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) System in the long term; Assess scientific research programs to see if they are collecting necessary information.

Evaluation of this statement:

The ITQ system is used around the world and avoids overfishing but puts the minimal possible limitations on who fishes, when they fish and how they fish. This system however requires a certain level of institutional capacity and scientific knowledge about stocks in cooperatives so can be implemented fully only in the long term.

It involves the allocation of quotas among fishermen by cooperatives based on historical catch so that truly active fishermen receive most of the quota. [Activity of fishermen may be monitored by other cooperative members; they can only be termed “active” if fishing is done on a regular basis annually]. Quotas allocated are ideally transferable enabling fishermen to enter or leave a particular fishery and collect sets of quotas (different tonnages from different stocks) that match the type of fish they would like to catch with the boat they have, their crew and their location. If the historical level of fishing is higher than the sustainable level, some fishermen could be paid to give up their rights to quotas in the initial allocation (buy-back). Funding for buy-back could come either from the government, environmental groups , or out of future resource rentals paid by those who stay in the fishery. The fishermen who stay will benefit from the newly sustainable stocks, so they will be better off even if they have to pay for buy-back.

The cooperative could choose to sell quota to their members and then distribute the revenue among the group.

Explore short term possibilities for creating tradable quota system for vessels; Buy-back program for vessel quota as part of establishing tradable quota system.

Evaluation of this statement;

The tradable quota system on boats is a simpler system which can be used instead of or as a transition toward a long term ITQ system. The Special law already limits the number of boats in the Marine reserve therefore it would be relatively easy to maintain this current moratorium in the Special Law on new vessels but allow existing permit holders to replace their boats or sell their boat permits to others (if they were going to sell their boat or use it for non-fishing purposes). Because the current number of boats still allows overfishing, the trade quota system would need to be combined with a program to buy back vessel permits and retire them, thus reducing the fishing fleet.

One disadvantage of limits on vessels rather than total catch by species however is that the system is not responsive to particular species that may be overfished. Similarly, this system doesn't encourage fishermen to focus their effort in locations where the stocks are strongest.

Strengthen short-term regulations to protect stocks. For example: make fishing seasons appropriate to biology of species as well as to limit catches and be consistent from year to year; use (fishing) gear regulations to protect species in a biologically appropriate way as well as reduce efficiency (to discourage fishing) in the short term; possibly relax regulations to serve only a complementary function as more efficient regulations by International committee are implemented.

There is also the possibility of:

- Offering other economic possibilities to fishermen [such as training them as park rangers or coast guards for example] so as to encourage them to leave fishing

- Training fishermen and providing them with starting capital (in the form of loans maybe) so as to get them more involved in offshore pelagic fisheries which is something locals are currently interested in but requires significant capital and experience.

- Pressure on target species could be reduced by providing incentives for locals to fish other species such as the Whitefish which is not so commercialized as there exists only one processing plant for export of this species in the Islands presently on San Cristobal.

Building processing plants for this species on other Islands could reduce pressure on target species.

[top]

Implementation

The issue of enforcement is a complex one. Currently, several good regulations are in place but are not effective because they are hardly ever implemented.

The GNPS park rangers are in charge of enforcing regulations. They are however relatively small in number and poorly equipped with patrol and enforcement tools. The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society also carries out patrols in the reserve. In general, this organization assists national and international bodies in the enforcement of International law under the authority of the United Nations World Charter for Nature (Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, 2004) and has an agreement with the GNPS to do joint patrolling of the reserve waters.

The following are suggestions for effective enforcement.

- It is possible for the Ecuadorian navy which currently patrols national waters to carry out investigations on foreign vessels in addition to large Ecuadorian vessels to ensure that these are not involved in industrial fishing in pelagic fisheries around the reserve.

- Sanctions to defaulters should be made heavy such that profits made by them will look derisive in comparison. Defaulters shall not only be the fishermen physically carrying out the fishing but also those buying their product.

- Training programs for park rangers and coast guards could be put in place by the International committee. These programs would serve to train as many park rangers as are needed out of the local Galapagos population especially current fishermen thereby offering other economic possibilities to them and their offspring. Through the International committee, not only scientists but specialized personnel from the countries on it could help to instruct and train rangers. Training future educators should also be good as this will enable the instructing immigrants to return to their countries.

- In current consideration is the declaration of the GMRR waters a “Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA)” by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO however does not make physical provision for enforcement of the laws enacted by any individual state to protect a PSSA declared in their territorial waters. But it can have maritime states (especially those around Ecuador) put up a machinery through which these laws are enforced. With regard to shipping and fishing activities, the states concerned make sure that vessels flying their flag (i.e. registered by them or simply national vessels) comply with the provisions of the PSSA treaty. Periodic controls are carried out to this effect and special patrols can periodically be carried out by NGOs and other organizations funded by the United Nations¹.

- To aid enforcement, regulation needs to be developed together with fishermen, needs to be complemented by strengthened knowledge and institutions, and needs to be simple. In the short run, environmental imperatives may require that these efforts are complemented with cruder forms of regulation, such as fishing seasons or gear restrictions, that protect fishing stocks. As other forms of regulation become more effective, these could be altered so they do not act as limitations on total effort.

- Through the International trust, more funds should be allocated for GNPS supplies and equipment such as eco-friendly patrol boats and law enforcement equipment (handcuffs and stun guns for example). Inspections could then be made more frequently and regulations implemented efficiently.

International effort can better address pelagic fishing around the Galapagos. The increased ability to give fisherman concessions will help to stabilize the situation; for example, “Galapagos fishermen end protest over net bans after concessions” (Deutsche Presse-Agentur. February 28, 2004). The Biopreserve will bring a stable political framework for administration and enforcement of the law. An international committee allows for negotiations between countries that transcend just the Galapagos, which is in accordance with the recognition that the problem of the Galapagos cannot be analyzed in isolation. For example, to convince Japan to decrease pressures of sea cucumber and shark fin fishing in the Galapagos, the United States might agree to help end the moratorium on whales (specific species like the Minke whale) by the IWC (International Whaling Commission).

There are several pressing issues that the international committee will consider. They will consider extending no-take zones to network them and make them more effective, essentially creating zones to protect the spillover effect of normal fish migratory patterns. They must also regulate small-scale intensive fishing gear along the shores.

The committee will also look into converting fishermen’s activities to non-extraction, while acknowledging feelings of resentment due to lack of skills and loss of independence. Such conversion will only be done freely but will be encouraged by making other activities more economically viable. The defined boat size of artisanal fishing as well as the methods used will be regulated by the commission. In addition, Usury Laws may be established to prevent hiring of middlemen to exploit fisheries.

[top]

Sources

- Kerr, Cardenas and Hendy. 2004. “Migration and the Environment in the Galapagos: An analysis of economic and policy incentives driving migration, potential impacts from migration control, and potential policies to reduce migration pressure.” Motu Working Paper 03-17. Motu Economic and Public Policy. "*" in the paper refers to citations made by the above source.

- Bensted-Smith,Robert,ed.2002. “A Biodiversity Vision for the Galapagos Islands.” CDF and WWF.

- GNPS. 1998. Management Plan for Conservation and Sustainable use of the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

- Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. 2004.

[top]

Copyright!

All rights reserved.

Webmasters