Ontario

Ishpatina Ridge - 2,274 ft

Date climbed: October 9, 2011

Eric and Matthew Gilbertson

The summit of Ishpatina Ridge

A panorama of the summit

The road got washed out past this point, and was only passable by mountain bike. Some unlucky mountain biker didn't quite make it, though.

This is the washed out section

We later had to ford the Sturgeon River

Knee-deep water in the middle - not too bad.

We got some respite from the bushwacking by following this lake shore

Matthew on the tue summit (a large boulder south of the tower)

Eric sliding to a stop at the car

Ishpatina Ridge - Highest Mountain in Ontario

Ishpatina Ridge - 2274ft

Highest Point in Ontario

Eric and Matthew Gilbertson

10.7.11-10.9.11

1670 miles driving

30 miles mountain biking

7 miles hiking

1 mile bushwacking

LINKS:

Our Canadian High Points Page

Our Adventures Webpage

Author: Matthew

"So you guys drove all the way up here just to climb that mountain?" the US border patrol officer asked doubtfully. From his perspective it was a legitimate question. Although he probably didn’t know the exact location or name of Ontario’s Highest Point – Ishpatina Ridge – he had guessed (correctly) that it was a considerable distance away from the border crossing here in Ogdensburg, NY. In terms of distance alone we were 75% done with our three-day-weekend mini-expedition, having driven 26 hours already, with 8 more to go. He probably also guessed (correctly) that the highest point was no more than an isolated little hill deep in the Ontario wilderness, dozens of miles from any road or human habitation.

“Yep,” we answered. To us it seemed like a perfectly valid reason to visit Canada. Come on, it’s the highest point in all of Ontario, why wouldn’t you climb it? Sure, it had involved thirty miles of mountain biking, four miles of hiking, and two miles of bushwhacking on top of three days of solid driving for just one hour on the roof of Ontario, but had it been worth it? Absolutely.

The border patrol dude thought about it for a moment more. “All right, you boys are all set. Welcome home.”

----

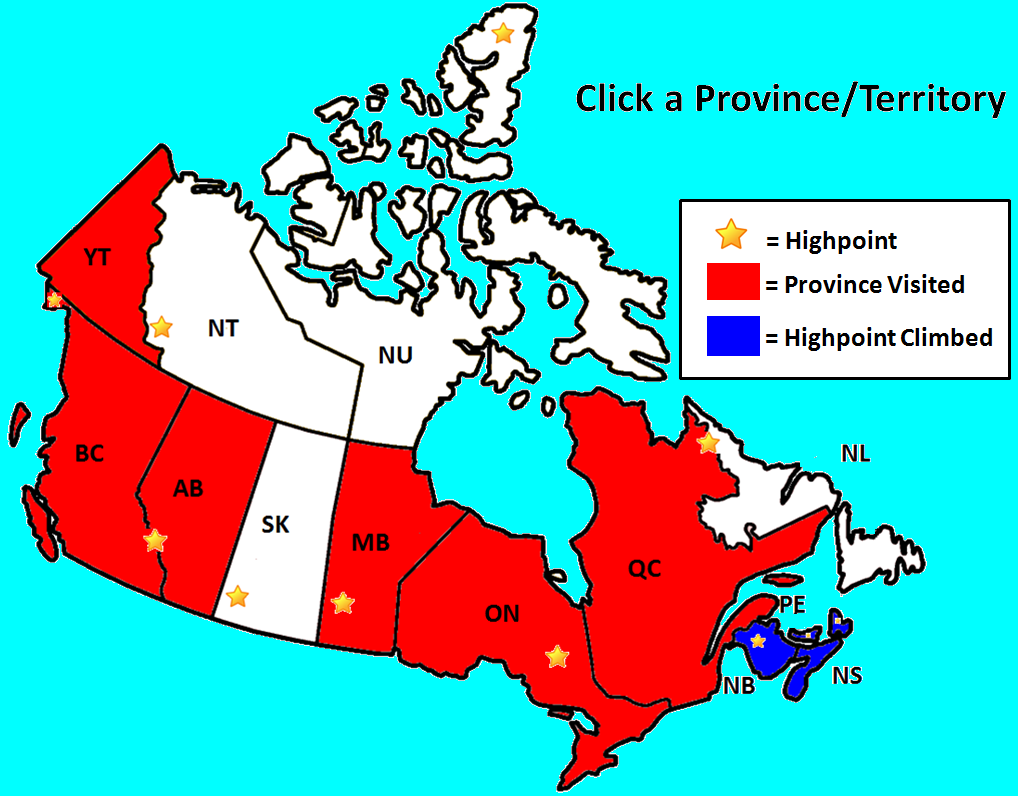

Our quest for the Canadian provincial & territorial high points had begun in earnest three months earlier on top of White Hill, the highest point in Nova Scotia. With just one state high point left – Texas – we had been running out of highest points reachable in a “weekend” from Boston. So it was time to move on to Canadian High Points. On that particular three-day weekend we had climbed Nova Scotia’s White Hill, Prince Edward Island’s Glen Valley, and New Brunswick’s Mount Carleton. It too had involved more than 30 hours of driving and had expanded our concept of what is possible during a three-day weekend. This weekend we hoped to raise the bar even higher by visiting Ishpatina Ridge.

From our Google Maps research we found that it would take seventeen hours of driving just to get to the base of Ishpatina Ridge. Seventeen hours of one-way driving from Boston can also get you to Myrtle Beach. Or Chattanooga, TN. Or Chicago, IL. But you probably wouldn’t think of driving to Chicago on a three day weekend – it’d be much nicer to fly. Since tickets to south-central Ontario weren’t too cheap, however, we concluded that we’d be driving. Columbus Day weekend presented the perfect opportunity for us to execute the trip – there wouldn’t be any snow on the ground yet but it would be cool enough that we probably wouldn’t have to deal with mosquitoes. So on Friday evening we ducked out of lab a little early, grabbed a rental car from Budget, and hit the road.

An infinity-star hotel

Unfortunately Google’s prediction of 17 hours didn’t take into account the fact that every man, woman, and child in the greater Boston area was also trying to head north on Friday afternoon. We joined the exodus at around 3:30pm. Most of the streets heading out of Cambridge were in total gridlock. We retreated back to campus and I used my laptop to find a secret-ninja route to I-93. We slowly gained some miles and after two hours the logjam of cars finally broke up and we had open road in front of us. We figured that if you could plot the traffic density versus distance from Boston it would be an asymptotically decreasing function all the way to Ishpatina Ridge.

We opted to take the slightly-longer, though more interesting, route through Vermont and upstate NY instead of the NY Thruway through Buffalo. By 11:15pm we crossed into Ontario at Cornwall and had the road all to ourselves. We were feeling energized and awake so we kept on driving. I had heard that this was moose country so I pulled up behind a semi and put on the cruise control. We figured that we’d rather the semi hit the moose first.

Around 1:50am our internal batteries started running out. We had made it past Ottawa, near the hamlet of Arnprior. (I get a kick out of that town name every time I say it.) “Uh oh, Eric, I’m tired, where shall we sleep tonight?” I asked.

“Hmm. Would you prefer a three-star, four-star, or infinity-star-hotel this evening?” Eric asked.

“I’d like to check out the infinity-star hotel this time, please, if there are rooms available.”

“I believe you’ll find the infinity-star hotel at the next side road.”

So I slowed down and turned onto the next side road. Wait, a flea market? How could this be the infinity-star hotel, I wondered. So I drove to the opposite side of the road and right on cue found the grand hotel entrance. A small dirt road led off into the woods, but I abruptly stopped because a thick steel cable across the road suggested that no rooms were available.

“Well, there’s probably not even a lock on it, why don’t you go check Eric?” Eric stepped out, and upon further investigation discovered that sure enough, it wasn’t even locked. He triumphantly pulled the cable back and with a flourish gestured for me to enter. We drove fifteen more feet down the road, set up the tent, and had a tranquil sleep in Ontario’s one and only infinity-star hotel (GPS coords: N45.44610 W76.56122).

We figured we’d benefit from sleep so we didn’t set an alarm and work up with the sun around 8:30am. There was still a lot more driving to do so Eric drove while I very carefully ate my power breakfast of cereal + powered milk. For the next 400km we didn’t have too many decisions to make, just drive west on the Trans-Canada Highway.

The expedition begins

Just outside of Sudbury we headed north. Now things were about to get interesting. We flew through Capreol, the last little outpost, and turned right onto the Gauthier Lumber Road, the beginning of the gravel. It was time to put the gamefaces on. This was where the little road trip ended and the expedition began.

We weren’t the first people to visit Ishpatina Ridge. Luckily plenty of other people had mapped out the route, so all we needed to do was print out the maps and follow them. By far the best map we discovered is located here. It had been a busy week for me so I didn’t have too much time to research the route. Eric had printed out some maps and I quickly recorded some GPS tracks from another person’s trip from 2006. I figured that one GPS track ought to be as good as any other. 2006 did sound a little dated but the route shouldn’t change in 5 years, should it? It would turn out to be a costly mistake.

I drove our little silver Volkswagen Jetta while Eric navigated. As we headed deeper and deeper into the Temagami wilderness we were stunned by the beauty of the fall colors. The leaves weren’t even thinking of changing in Boston, but up here in the North Country Fall was already winding down. The hills were covered with a spectacular mix of yellow birch leaves and evergreen spruce.

Boom! A loud bang underneath the car brought us back to reality. The road was getting rougher and rougher and big rock had just slammed into the undercarriage. Luckily we knew that Budget wouldn’t be looking underneath the car when we brought it back. But nevertheless I needed to activate our rock-avoidance system. “I thought you said that any road-worthy car can make it up this road, Eric?”

“That’s what the website said,” he responded. “Maybe they just have lower standards for roads here in Canada.”

We kept on driving. 10 miles in. 20 miles. 30 miles. Pretty soon we came upon our turnoff and headed up an even rougher road. A bullet hole-ridden sign nailed onto a tree ominously warned “Road Washed out at 52km.” “That’s weird,” I said, “because we still need to drive seven miles on this road.”

As we pushed on the road deteriorated even more and a few big rocks scraped agonizingly against the undercarriage. “Enough,” I said, “it’s your turn to drive.” I got out and walked alongside the car as Eric slowly drove on. I helped guide him over a few big rocks until pretty soon we came upon a minefield of grapefruit-sized mini-boulders strewn across a steep hill. In a truck the road would have been no problem, but our mere five inches of clearance were no match for the Canadian gravel. Defeated, Eric backed carefully down the rocky hill and into a little pull off.

“That’s just plain weird,” I said. “The road must have gotten a lot worse since that trip report was written.”

“Yeah we followed the GPS track that you recorded, I don’t know what’s going on.”

But we wouldn’t be defeated that easily. We had brought a secret weapon: mountain bikes. Our car might not be able to drive up this road, but with mountain bikes we could traverse any terrain.

Even though this meant we’d have to do 15 miles of (one-way) mountain biking instead of just the 4 we had planned on, we figured it’d still be perfectly doable given that there wouldn’t be much elevation gain and there were still three hours of daylight. In order to get our gear over to Budget we each had brought our big backpacking packs and I had even brought two bike panniers. So this meant we’d be totally capable of transporting our camping gear while we mountain biked. This was going to be an even more epic trip than we had planned, but we figured it’d still be within the realm of possibility.

The margin for error gets slimmer

“Oh, that’s right, my tire’s flat,” Eric said with dismay as we unpacked the bikes from the trunk/backseat. The previous evening while we were driving we had suddenly heard the inexplicable sound of one of our bike tires spontaneously deflating. It was the strangest phenomenon because the tire wasn’t being compressed, in fact nothing in the car was even touching it. But we figured we’d just patch it at the trailhead.

As I assembled my bike Eric had an unfortunate realization. “Uh-oh, the valve is sliced, so we can’t patch it.” I immediately froze. This was serious. We could make do with nearly any other bike failure mode except an unusable tube. Thankfully though I remembered that I had packed one extra tube so I gave that to Eric.

But this meant our margin for error was now even slimmer. We couldn’t afford another busted tube. If when Eric was inserting the tube he accidentally sliced the valve then we would be toast. We wouldn’t be able to ride. Plus, my own tube already had six leaky patches on it. I had been planning to use that extra tube for my own bike.

I had only brought one spare tube because on none of our mountain biking trips had we ever needed two. But this was going to be more than a typical mountain biking trip. Suppose we found ourselves 15 miles down the road and we had another catastrophic tube failure. Then we’d be walking the whole way back. I started getting a sinking feeling – almost a feeling of fear – that we’d come all this distance and wouldn’t be able to make it to the top.

Sure we had ridden on 500 miles of rough Alaskan gravel [url =http://mitoc.mit.edu/gallery/main.php?g2_itemId=125362]three years ago on the infamous Dalton highway[/url], but back then we were highly prepared with two bike pumps, five extra tubes, patch kits, and every bike tool you’d ever need. Today was our wake-up call that mountain bikes are more than just a fun way to exercise – they can mean the difference between an hour of cruising and five hours of sheer drudgery.

Eric gingerly inflated the tube and it held air. Whew, we breathed a sigh of relief. A pickup truck drove by and the guys waved curiously to us. They must have been thinking, “What in tarnation is this car from Massachusetts doing way back in here?” I almost approached them asking if they could give us a ride in the back, but we weren’t quite packed up yet so I didn’t want to waste their time. Soon we had all our gear together and bid farewell to the silver Jetta. “We’ll see you tomorrow,” we said to it.

A lucky find

The road maintained its roughness so we were happy that we had traded the car in for mountain bikes. After a few miles we came upon a sign reading “DANGER: Bridge Removed, Do not proceed.” A dead bird hung ominously from the sign. But it wasn’t the bird carcass or the words on the sign that drew our attention, it was the bicycle hanging from it. The dilapidated bike appeared to have been abandoned years ago. The seat was shredded, the back wheel was nowhere to be found, and the front tire was duck-taped to the rim. It looked like someone else had worse bike luck than us and had gotten desperate.

I glanced on the other side of the road and noticed the rear wheel hanging from a tree. It looked to be in good shape. Could that possibly be our spare tube? Our margin of safety? I carefully removed the tire and lo and behold there was a tube! Sure it wasn’t really the right size, but if things got desperate we would make it work. It was as if someone had put that there for us. We both breathed a big sigh of relief and kept on pedaling.

Our car definitely couldn’t have made it past this obstacle. The road had gotten washed out years ago leaving a gigantic crater where the bridge had been. And the only way to proceed on the road past this point would be via mountain bike or four-wheeler. “Vindication!” I yelled to Eric. “Aren’t you glad we brought the mountain bikes now? We’d be out of luck without them.”

The phantom road

We kept on pedaling but things didn’t seem to add up. The nice map we had found online was made less than a year ago but it mentioned nothing about this washout, which had obviously happened more than a few years ago. But we had to be on the right road, because this went straight to the “trailhead” and was the same route other people had taken in 2006. Weird, we thought, and kept on pedaling.

But before long the puzzle of the rough road was finally solved. We turned a corner and suddenly came upon a really nice, super-wide and super-smooth gravel road with obviously fresh tire tracks. “Aw crap,” I said, “this means that we could have driven to this point.” Ugh, we groaned, we had just made this trip harder on ourselves than it needed to be.

With disgust we continued pedaling and pieced the puzzle together. The road back there had washed out after the 2006 trip report was written. This new gravel road was created a few years later and was the one mentioned in the really good map. Unfortunately I had grabbed the GPS waypoints from the 2006 trip report. To make things worse the road was so new our GPS didn’t have it, so we couldn’t have known to take it. “Well at least well have more to write about in our trip report,” I said.

With mixed feelings of dismay and pride we pushed on to the Sturgeon River crossing, which is the location where all sources indicate you should park your car and start biking. We switched our shoes out for crocs and forded the river. Fortunately the water was pretty low, but even so it was still up to our knees. But amazingly a truck had managed to drive through, as evidenced by the tire tracks on the other side.

At the next creek crossing we had our only substantial encounter with a real Canadian local of the entire trip. An orange-vested hunter drove up with a four-wheeler and asked “you guys headed to the tower?” He was referring to the fire tower on Ishpatina Ridge. “Yep, we’ll camp at the end of the road tonight,” we answered. He pointed to Eric. “What are you doing here wearing blue? It’s moose hunting season! You should be wearing red! You could be mistaken for a moose.”

We figured you’d have to be a pretty bad hunter to mistake a mountain biker with a big backpack for a moose, but nevertheless I decided to stay in front since I happened to be wearing red. The hunter was a nice guy and said he’d tell all the other hunters around to watch out for us. We bid him farewell and continued biking.

Before dark we finally reached the end of the mountain-bikeable stretch of the expedition and ditched the bikes in the woods. If there’s any place we’ve ever visited where you don’t need to lock up your bikes, this is it, we figured. There ain’t gonna be anyone else in here for a long while. We dragged our camping gear a little ways down the recently-cut Scarecrow “Trail” and found a good campsite (N47.27023 W80.78364). After a hearty helping of Lipton noodles we fell asleep to the quiet of the Canadian wilderness.

The home stretch

Thankfully the October sunrise gave us a break and let us sleep in until 7am. If it had been July we’d be up an hour earlier. We scarfed down our power breakfasts and hit the ground running, leaving the tent and sleeping bags to be packed up on our way back.

This was turning into a real expedition. We had taken each mode of transportation as far as possible and had used almost every gear item we had brought with us. We had ditched the car when we couldn’t drive it any farther. We had dropped the bikes when the gravel road turned into a rough hiking trail. And we had abandoned the tents and sleeping bags because we wanted to go fast and light to the summit. We now carried just the bare essentials: food, water, iodine, GPS, cameras.

Until just a few years ago the route to Ishpatina Ridge had involved a substantial amount of bushwhacking. Luckily in recent years though some considerate Canadians had cut the Scarecrow Trail which would shave off two miles of bushwhacking. By New England standards you might not consider it to be much of a trail, but it sure beat thrashing through the dense undergrowth. With the trail we could cruise, not needing to consult the GPS or second-guess out route as you would with bushwhacking.

Soon the trail deposited us onto the shores of the magnificent Scarecrow Lake. The sun had just risen on this tranquil morning and the water was as smooth as glass. Mist rose from the water and drifted through the bright yellow birch trees. We could hear some loons off in the distance. We were indeed a long ways from Boston. It would have been fun to swim out to one of the little islands but we had other plans for today so we kept walking.

Fortunately the water level was pretty low so we could walk most of the distance along the lakeshore with only occasional forays into the bush. We had read that until recently the most “popular” way to reach Ishpatina Ridge involved a three-day canoe trip along the Sturgeon River and through numerous small lakes. That would be pretty awesome, we thought, but we were glad that the overland route was pioneered to enable those of us in a hurry to reach the top.

At the end of Scarecrow Lake we met up with the well-traveled Tower Trail. To us it seemed weird that after all this hiking and bushwhacking there would suddenly be a well-maintained trail in the middle of the wilderness. But we had read that the trail was originally built in the early 1900s and used by the firemen to travel to the firetower on top of Ishpatina Ridge. A floatplane would bring workers to the lake so they’d only need to hike 2.5 miles to the summit. So this meant that it would be smooth sailing from here to the top.

We had picked the ideal weekend for Ishpatina Ridge. Under beautiful Fall foliage and bright sunlight we topped out on the highest point in Ontario at 9:50am. Ishpatina Ridge was ours! The old 100ft tall firetower christened the summit. Originally we had planned to climb to the top of the tower and had brought slings, beaners, and a harness to clip in along the climb. But the ladder looked a little rickety and a tad bit exposed, so we chose instead to admire the view from ten feet up the tower.

We could see nearly 60 miles in every direction without a single indication of human presence (well except for this giant firetower). We figured you probably couldn’t reach a more remote location by car in 1.5 days from Boston. There were nothing but hills and lakes all the way to the horizon and it was nearly the peak of the Fall colors.

Of course we captured the requisite juggling photos but both of our knees were bothering us so we skipped the jumping photos. My cell phone had several bars of service, but none of my texts would send, I suppose because we were just too far from the nearest cell phone tower. It had taken us so long to get here that we decided that by gosh we’d make it worthwhile. We hung out for more than an hour on the summit, capturing plenty of panorama photos to document the occasion.

Halfway done

But as nice as the view was it was hard to shake off the notion that we were actually only halfway done with our trip. We took one last leak around on the summit and began the long journey back to Boston. Even though we were still in such an awesome place with many miles of hiking/biking to look forward to, each step down was bringing us closer to civilization. On the way up each step had come with a feeling of excitement and anticipation, but with each step down we realized that our time in the wilderness was running out.

Since it was such a nice weekend we half-expected to see someone else on their way up. But we ended up having the mountain all to ourselves, and didn’t see another person until later that day. Around noon we made it back to camp, packed things up, and hopped back onto the bikes. My tire was low but still held air, so I figured that as long as I took it easy on the rocks we’d make it down without incident. The nice thing about riding a bike is that all of the uphills turn into downhills on the return trip. For all of our effort spent climbing the previous day we were rewarded with adrenaline. We tore down the mountain triumphantly, racing to beat the sunset.

Having long since been kicked out of the dry-shoe club, I blasted through a few of the larger creek crossings care-free. I had to dismount when crossing the Sturgeon River, however, because it was knee-deep in the middle and a little tricky to balance. By 4pm we were back at the car, twenty-four hours after we had left it. As we packed the mountain bikes in we reflected on the distance we had pedaled. Even though at the beginning we were a little disappointed at our mistake that cost us an extra 20 miles of mountain biking, by now we were actually a little proud that we had made the trip that much more epic.

As we drove down the rough road a hunter dude on a four-wheeler stopped to let us pass by. With confidence and coolness we gave him the one-finger wave and he nodded approvingly back to us. He was probably wondering just why two guys would drive all the way from Massachusetts to this rough little gravel road in the middle of the wilderness.

Back on cruise control

With the sunset at our back we pulled onto the Trans-Canada highway and turned on the cruise control. It was nice to have 115 horses working for us, and all we had to do was keep the steering wheel pointed in the right direction. Despite all the excitement we had enjoyed a good sleep the past two nights so we had plenty of energy to keep driving. Later that night we ended up camping at the same infinity-star hotel as the previous night, just outside of Arnprior, Ontario. The cable was still unlocked just for us.

As we started driving the next morning we realized that we were actually a little ahead of schedule. We figured it’d be awfully lame to get back to Boston early on a perfectly good holiday weekend so we decided to take the scenic way back through the Adirondacks. As we crossed into Vermont we realized that we still had some daylight to spare. Coincidentally there was a mountain close to our intended route called Mendon Peak on the New England Hundred Highest list which we hadn’t climbed yet. And even more coincidentally, based on our research it appeared that much of the route would be mountain-bikeable and what do you know we had mountain bikes in the trunk.

So we decided to put the finishing touches on our masterpiece of a weekend by climbing Mendon Peak. But that’s a story for another trip report.