| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |

| Vol.

XVII No.

5 May/June 2005 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

International Students and Scholars:

A Legacy for MIT and the U.S.

The United States presently enjoys a system of higher education that is the envy of the world. This premier position allows us to attract the most talented, most driven and highly motivated international students and scholars in the world. We benefit from the presence of these students and scholars in myriad ways. These benefits can be difficult to quantify; in this brief analysis, we use the perspective of MIT's experience over the past 150 years to evaluate the contributions that our international student and scholar population makes to us and to our nation.

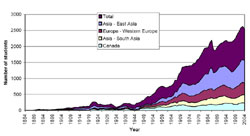

A Century of International Students

MIT has welcomed international students essentially since its inception; the first student from Canada came to MIT in 1866, the second year MIT offered classes. This student was followed by a steady stream of students from across the globe throughout the nineteenth century. Click here for two examples. By 1900, some 50 students had traveled to Massachusetts for study; however, the numbers of international students only really began to grow after the Second World War, when an influx of students began in earnest, as shown in the figure.  The rapid rise of international students from East Asia, led by China, changed the demographics of this group beginning in the 1950s. The change in immigration law in 1965 opened up the doors to a steadily rising influx of international talent.

The rapid rise of international students from East Asia, led by China, changed the demographics of this group beginning in the 1950s. The change in immigration law in 1965 opened up the doors to a steadily rising influx of international talent.

World events and political decisions have always had a strong impact on immigration. We see this in MIT's international student population as well.

World wars curtail the flow of students while peacetime pressures, such as changing immigration laws (1965), the demise of the iron curtain, the Vietnam War protests (1968), and the Asian financial crisis (1997), cause their respective ebbs and surges.

The "Best and Brightest" International students - Global Contributors

The United States has been the destination of choice for international students and scholars for the past 50 years. Just as MIT's experience shows, the number of foreign students has risen steadily since the 1970s, and last year, according to the Institute for International Education, there were more than 500,000 international students enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities (see www.opendoors.iienetwork.org).

One might ask what becomes of the international students we recruit and train. We are aware of the great contributions immigrants make to our culture and the leadership roles those who are educated in the United States often assume.

Our current visa system is predicated on applicants demonstrating that they have no "intent to immigrate." Thus, officially we want them to come here, pursue their studies, and then to return to their home country.

This appears to have some merit if one holds the view that to remain in this country, these highly educated immigrants would compete for jobs with domestic candidates. It is also true, however, that those who remain in the U.S. contribute greatly to our community, our economy, and our science and technological leadership.

Many of our international graduates return to their home country. While they are not directly contributing to our economy, in today's global environment the alumni are contributing to our economies and those of others both directly and indirectly. In addition, those who return and gain positions of leadership are more likely to share our values and to try to emulate our technical and business structures. This level of diplomacy may be far more important than we can imagine.

| Back to top |

Those who stay

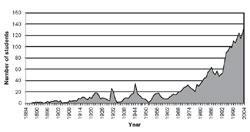

The United States has always and will continue to gain strength and leadership in science and technology from its immigrants. A growing fraction of the U.S. engineering faculty is foreign born, and greater than one-third of the Nobel Laureates we claim were born elsewhere (see www.nobel.se/index.html). International students often go on to leadership positions in large and small companies. It becomes apparent that we attract not only the "best and brightest" students to travel abroad for study, but perhaps we also attract those more inclined to be "risk takers" who end up in leadership positions in academia, industry, and entrepreneurial activities. These innovative individuals thrive in the American system of research, education, and venture support. Click here for two examples. As one measure of their innovation MIT has seen a rapidly increasing number of patent disclosures having at least one inventor from among our international student and scholar community.

As the distribution of international students changes, so does the rate with which they choose to remain and pursue a career in this country. Tracking income tax records, Michael G. Finn has shown that the number of doctoral recipients remaining in the U.S. two years after receiving their degree has increased from 49 percent in 1989 to 71 percent in 2001. (See Michael G. Finn, "Stay Rates of foreign doctorate recipients from U.S. universities, 2001," National Science Foundation, November 2003.)

Electrical engineering, computer science, and the physical sciences had the highest fraction of international students remaining after graduation and those most likely to remain here come from China (96 percent) and India (86 percent).

We do not know the stay rates beyond two years, since 2001, nor for postdoctoral scholars. It is clear that many international graduates become more global citizens going on to mobile careers abroad, in their own countries, or in another country.

Those who return home

Many international students choose to return to their home country and there they use their talents as leaders in many areas of government, industry, and academia. In addition to their formal education, these alumni retain strong attachments and identification with their alma mater. Their ease with our traditions, culture, and values is widely regarded as an important facet in their relationship with our country. Generally, those who have lived abroad and experienced another culture have a higher respect for those from different countries. One's perspective on world events is forever changed by viewing them from another part of the globe. The U.S. State Department maintains a website showing the tremendous leaders who have received part of their training in the U.S. as international students. (See "Foreign Students Yesterday, World Leaders Today" http://exchanges.state.gov/education/educationusa/leaders.htm.)

MIT is proud of the many influential alumni who have returned to their native land to improve the quality of life there and enhance productive international relations. Click here to see two such individuals from the twentieth century.

The network of academic influence should also not be overlooked. As talented individuals receive their education in the U.S. and return to teach in their home country, these faculty colleagues then send their best and brightest back to their alma mater, providing important connections to lead the most talented students to the U.S. In MIT's alumni database we find that over 1000 of our alumni are working in higher education abroad. Thus, our educational influence is magnified when one considers the production of professors who in turn educate further generations.

| Back to top |

Maintaining the Balance – Threats to our Ability to Attract International Students

We face a challenging task of balancing our national security interests with promoting the valuable exchanges we have with international students, scholars, and visitors. In the past few years, we have seen the significant effects of U.S. immigration policy on the time and effort it takes to obtain a visa for study or research in the U.S. The implementation of the SEVIS system to regularize the information we maintain about international students and scholars has improved many aspects of the process, although ensuring the accuracy and reliability of those records is critical to avoid jeopardizing students' status.

Some aspects of the visa granting process have improved, with the State Department putting international students and scholars at the head of the queue for the now mandatory interviews; and the "Visa Mantis" security clearance processing time is improving to the point where over 85 percent are completed within 30 days. There are also recent proposals to extend the term of the visa to be more commensurate with the term of study. Despite this progress, there remains a disquieting sense that the U.S. has become less hospitable to international visitors. The specter of students, postdoctoral scholars, and faculty stranded abroad while they are reevaluated for their visa may cast a shadow that will be difficult to dispel.

The perception that the international student immigration process is too capricious and too onerous may degrade our ability to attract the talented students to which we have become accustomed. Meanwhile, we see increased competition for international students.

Anecdotes abound of our allies benefiting from the challenges our international students face.

Each European leader who visits MIT mentions that the U.S. problem with student visas is to their benefit. (And the competition is not just from Europe.) In 2003, international student enrollments in Australia grew nearly 11 percent compared to the previous year. During 2003, there were a total of 303,324 enrollments of international students in Australia primarily from Asia. (For a summary of international student enrollment trends in Australia, see aei.dest.gov.au/AEI/MIP/Statistics/StudentEnrolmentAndVisaStatistics/Default.htm)

We continue to seek improvements in both the processes and the perceptions of the U.S. as a welcoming destination. Several issues come to mind:

- Consular officers and port-of-entry officers need to have sufficient support and training to provide consistent decisions. They need access to reliable and accurate SEVIS data for these decisions.

- We waste valuable and scarce consular resources on repetitive processing of visa applications for those with a proven track record. Repetitive security checks and inefficient visa-renewal processes cause lengthy visa issuance delays. Security clearances should persist for the duration of study unless significant changes have been made.

- Problems with the data in SEVIS severely undermine both the student's situation and the security we aim to provide.

A recent study by the National Academies (www.nap.edu/books/0309096138/html) provides a detailed analysis of the issues surrounding current immigration policies and the increasing competition for international students.

Summary

Clearly our international student and scholar community has much to offer MIT, the United States, and the rest of the world, now and in the future. There are numerous examples of influential people who, at one stage of their career, were international students in the U.S. We have much to lose if we make this talented community feel unwelcome or unable to study here. Hopefully we will not lose sight of the great strength and global security that comes from the free exchange of students and colleagues from abroad.

We will remain vigilant in our efforts to help improve immigration policy and processes. We will also continue to provide excellent service to our international community through our International Students and International Scholars offices. We may find ourselves in a new era where we must compete more directly with schools here and abroad to attract and recruit international students and scholars. Certainly MIT is ready to rise to this challenge and remain the premium destination for education and research for students within and beyond our borders.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |