| Vol.

XXIII No.

2 November / December 2010 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

From The Faculty Chair

MIT Promotion and Tenure Processes

In spring 2009, my predecessor Bish Sanyal asked Bob Silbey and me to co-chair a special faculty committee on MIT’s Promotion and Tenure Processes. A brief summary of our report follows, along with some thoughts on several longer run challenges facing our profession at MIT and in our peer institutions. The full report of our all-star committee is available at: web.mit.edu/faculty/reports/pdf/promotionandtenure.pdf.

Our charge was to review the full range of processes used in promotion and tenure decisions. Note, however, we were not asked to reconsider the intellectual and educational standard for making these decisions. Our committee reviewed the hiring, mentoring, and promotion/tenure decision-making processes followed in different MIT departments and Schools, examined the recent Faculty Quality of Life Survey data relevant to these processes, reviewed practices at peer institutions, and discussed drafts of the report with department and School Councils and with the Academic Council. We also reviewed the appeals processes available to candidates who believe MIT processes have been violated in their case.

The committee found considerable variation in processes across the departments and Schools. Some of this is natural and needs to be preserved, given differences in disciplines and department size.

The variations observed, however, also helped identify several common problems and a number of benchmark practices that other departments might consider adopting. For example:

Clear Communication at Point of Hire. We found that the processes and expectations for tenure are not always communicated clearly to new faculty at point of hire. We recommended that:

- Department heads should communicate promotion and tenure expectations orally and in writing when extending job offers to faculty candidates, and again once the faculty member is at MIT.

- Special care should be taken to communicate clearly expectations regarding the timing of possible promotion and tenure reviews for faculty hired with several years of prior academic or professional experience, since the standard timeline may not apply in these cases.

- In cases of dual departmental appointments (a growing phenomenon at MIT) the distribution of teaching and service expectations, along with the promotion and tenure processes and criteria that will be used by each department, should be communicated clearly.

Mentoring. We found wide variations in the methods and effectiveness of junior faculty mentoring and generally low rates of faculty satisfaction with their formal mentoring experiences. At the same time, we identified a number of very good mentoring policies from which we derived the following recommendations:

- Mentoring should begin at the point of hire with clarity about the responsibilities and expectations of both the mentor and the mentee;

- Departments might consider creating a mentoring committee (e.g., 2-3 mentors, one of whom is the principal mentor);

- The faculty member should be allowed to change mentors, in consultation with the department head;

- The mentor should have a voice in the promotion review process either as a member or a non-voting member;

- The department head has the responsibility for ensuring that there is good communication between the mentor and faculty member;

- Schools should recognize excellence in mentoring;

- The mentoring process should be highlighted at the New Faculty Orientation;

- The department head’s letter to the School Council proposing promotion or tenure should include the name(s) of the mentor(s) as standard information.

Given the clear need for improvement in mentoring, Associate Provosts Wesley Harris and Barbara Liskov and I have brought together some of our best and most experienced faculty mentors to learn from their experiences and to develop a new faculty mentoring guide that will be disseminated across the faculty. I hope that we see significant improvements in the quality and uniformity of mentoring.

| Back to top |

Letters. The number, gender differences, and use of letters generated considerable discussion and the following recommendations:

- MIT calls for reference letters from external peers for promotion to associate without tenure, associate with tenure, and full professor. Few other universities require letters for three promotion levels, and some outside reviewers resent being asked to write about the same candidate three times. The committee recommended the Academic Council consider whether it is necessary to continue requiring outside letters for promotion of tenured associate professors to full professor.

- There is considerable empirical evidence (from studies done outside of MIT) suggesting that letters for successful men and women candidates differ in significant and gendered ways: more personal commentary (with potential positive or negative connotations) for women than men; shorter letters with less specificity for women than men; more emphasis on ability in men’s letters compared to effort for women.

In general, there are more “standout” words in letters for men and more doubt raisers in women’s letters. [These findings are based on a discourse analysis of over 300 letters for successful professors of academic medicine: Trix, F, and C. Psenka (2003) “Exploring the color of glass: letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty,” Discourse and Society, 14(2), 191-220. See also, Watson, C. (1987) “Sex-linked differences in letters of recommendation,” Women and Language, 10(2), 26-8.] We recommend that this evidence be communicated to promotion and tenure committee members and department heads. Care should be taken to not allow such differences to influence their judgments. - There is no standard practice among departments and Schools regarding who is able to read the letters (both internal and external). The committee felt that all tenured faculty in the department should be able to see the full dossier and express their opinions of candidates for promotion without tenure and promotion to tenure. Full professors should be able to see the full dossier and express their opinions of all candidates in all cases.

- A number of departments reported difficulties obtaining a sufficient number of letters for some interdisciplinary candidates. There are fewer people to ask for a letter; the return rate can become small, and; committee members may lack sufficient knowledge of the different fields involved to determine the appropriate mix of letter writers. These problems may cure themselves with time; however, until then, special attention should be given to these issues by decision-makers at all levels.

Review Process. The process for reviewing a promotion or tenure decision as spelled out in Section 9.6 of MIT Policies and Procedures was found to be too general and was not well understood. With the able assistance of the General Counsel’s office, we therefore developed a more detailed statement of the practice that has been in place for such reviews and discussed it with School and departmental leaders, the Faculty Policy Committee, and the Academic Council. It has now been adopted and has become Section 3.3 of MIT Policies and Procedures. We hope this makes the process clear, transparent, and accessible in the event it is needed in the future.

I encourage you to read the full report to learn more about these and several other issues covered such as recommendations for shortening the increasingly lengthy personal statements written by candidates and eliminating use of candidate pictures (based on considerable social science evidence on their potential biasing effects). In the end, the fairness of our decisions depends on how diligent we are in following the professional standards and Institute and department-level policies guiding promotion and tenure processes.

Broader, Long Run Questions for Thought

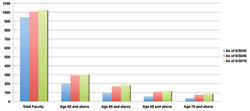

Looking beyond these process issues I see at least two important strategic concerns that warrant further discussion among MIT faculty and in the profession at large. The first is the aging of the faculty and the increasing challenges associated with that euphemism we have called “faculty renewal,” aka encouraging faculty to retire at a reasonable age. We all share the goal of opening up opportunities for new faculty hires. There is no better way to refresh our departments and to forge into the newest intellectual territories being explored by the best of the next generation’s scholars. But the accompanying chart illustrates the growing challenge we face. The MIT faculty is aging and more faculty members appear to be postponing retirement to a later age. Thirty percent of us are 60 years or older; 7 percent are 70 or older. These numbers are up considerably from a decade ago.

(click on image to enlarge)

What, if anything, should we do about this? Faculty in several departments have fostered a norm of retiring at or around age 70, specifically to open opportunities for new hires. An Institute-wide retirement incentive program has been in place for several years. Other strategies could be considered. I encourage dialogue and comments on this issue.

A second and more general issue relates to the attractiveness of our profession to young talented students, and particularly to women and underrepresented minorities. Just consider the hypothetical question: Would you recommend your daughter pursue a faculty career at one of our peer institutions knowing that it will require five or more years of PhD study followed by three to five years of post-doc employment, followed by seven to eight years pursuing tenure? Add up the years, the uncertainty of success in gaining tenure at our best universities, and the family life sacrifices required. Then compare these against her options outside of the academy. Given the opportunity costs involved, it is not surprising that we lose significant numbers of talented women and men at different stages of the pipeline, but particularly at the post-doc stage. Perhaps we need to rethink how we structure academic careers and the way we bring people into the academy.

These longer-term issues are just food for thought before you take time to relax with your families and friends for the holidays. In those pursuits, let me extend my best wishes to you all.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |