| Vol.

XXIII No.

5 May / June 2011 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Can Nuclear Disarmament Become a Reality?

In 1963, Jerry Wiesner, at the time MIT Institute Professor and special assistant to President Kennedy, met with the President and explained to him that because of above-ground nuclear testing, common rain was polluting the world. Wiesner urged Kennedy to ban above-ground testing, and the President agreed. One of Kennedy’s last acts as President was to fulfill this promise.

Wiesner’s meeting with Kennedy was just one of many remembrances shared by long-time MIT researcher Kosta Tsipis, as part of the May 4th forum, “Putting the Genie Back in the Bottle: MIT Faculty and Nuclear Arms Reduction.”

Co-sponsored by the MIT Faculty Newsletter, the Technology and Culture Forum, the Program in Science, Technology and Society, and the MIT Physics Department, the afternoon event featured speakers approaching the issue of nuclear disarmament from a variety of viewpoints.

Moderated by MIT Professor of Anthropology Jean Jackson, the forum began with a brief introduction by MIT Physics Department Head Edmund Bertschinger, in which he recalled being terrified of nuclear war in the 1970s and the school exercise “duck and cover.”

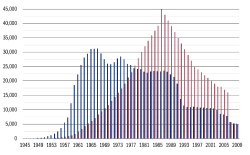

(click on image to enlarge)

Next Harvard Department of History of Science Lecturer and Kennedy School Research Fellow Alex Wellerstein provided an historical background, speaking on “Why build so many nukes?” Accompanied by an informative visual presentation, Wellerstein hypothesized six reasons why during the Cold War the U.S. built an absurdly and fundamentally unnecessary number of nuclear weapons.

- Lack of deliberation (secrecy)

- Inter-service rivalry

- Shift toward tactical nukes

- Problematic targeting models

- Endless quest for “certainty”

- A quest for supremacy, not parity

Kosta Tsipis, reflecting the co-theme for the forum of recalling and honoring past MIT professors and researchers who played an integral role both in initially creating the first nuclear bomb and subsequently leading the anti-nuclear movement, spoke of the role Jack Ruina, Henry Kendall (founder of the Union of Concerned Scientists), Bernard Feld, Herman Feshbach, Philip Morrison, Vera Kistiakowsky and others played throughout their years at the Institute. Tsipis recalled with great pleasure that when in 1979 President Reagan announced his Star Wars initiative, Tsipis wrote a piece condemning the whole idea – which appeared in Playboy!

Then James Walsh of the Security Studies Program at the MIT Center for International Studies spoke about the political, and not necessarily well-known, international efforts toward non-proliferation. He pointed out that the desire for nuclear weapons among countries was actually declining, as opposed to the commonly held belief that “everyone wants a nuke.” The record is actually one of restraint, he said: seventy-five percent of countries that considered acquiring nuclear weapons reversed course and ultimately decided against it.

Walsh spoke directly to the question/fear about Iran acquiring nuclear weapons, explaining why that possibility is far from inevitable. Among the points he made were:

- Iranian nuclear weapon acquisition was actually a capability decision, not simply fulfillment of a desire for a nuclear weapon.

- There has not been the typical crash program to create nuclear weapon capability

- Iran publicly disavows the desire for nuclear weapons, saying that nuclear weapons violate laws of Islam.

- Iranian society is actually deeply divided over the nuclear capability question.

- Iranian desire for nuclear weapons became even more unclear after their elections in June 2009.

Finally, Aron Bernstein, Professor Emeritus in the MIT Physics Department, spoke on “putting the genie back in the bottle.” Bernstein expressed optimism about the possibility of true nuclear disarmament, saying he was heartened by steps taken by the Obama administration. He noted the non-proliferation treaty and the recent START treaty as positive steps in the right direction. He further emphasized the importance of the U.S. Senate passing a comprehensive Test Ban treaty, and acknowledged that public support and political pressure from voters would be the most crucial factor to ensuring passage.

Still, Bernstein’s optimism wasn’t of the naïve kind. He pointed out how even today U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons are on hair-trigger alert; that the Indian sub-continent is probably the most likely place for a nuclear conflict to take place; and that the still enormous number of nuclear weapons presents/constitutes a fearsome threat to us all.

He pointed out the Los Alamos scientists who had developed the nuclear bomb thought that “1 bomb = 1 city” was the right formula to apply; they couldn’t even have imagined a nuclear stockpile of more than 100 nuclear weapons – as opposed to the 5000 that the U.S. still possesses today.

A feeling of both increased knowledge along with cautious optimism permeated the room after the question and answer period that followed. Many MIT professors have clearly been at the forefront – both scientifically and politically, currently and historically – in the nuclear disarmament debate. With continued awareness and well-planned intervention the reality of a nuclear weapon-free world might actually come to pass.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |