| Vol.

XXVII No.

2 November / December 2014 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

The A2 Problem Set in Undergraduate Education

Access and affordability are two concepts that have become inseparable. Google them as a single term and there is no end to the mention of access and affordability in housing, food, energy, health care, and higher education. Access: the ability to reach, approach, or enter. Affordability: the ability to purchase. Together, they form the A2 problem.

Within higher education, access and affordability refer to removing the financial barriers to achieving one’s educational aspirations, with access most often associated with students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and affordability with middle-class students. Together access and affordability are a weighty term that becomes a lightning rod for the ever-growing public concern that undergraduate higher education in the U.S. is out of reach for ordinary citizens.

Access and affordability are as much about perception as reality, if not more so. Often, changing the belief that something is not possible is the major obstacle to overcome. So to put this all in perspective, our core question becomes, “Is MIT affordable for all families?” The simple answer is yes, but proving that is more complicated.

So let’s unpack this A2 problem set. We operate on a high tuition/high aid model, as many private selective research universities do. It is true that our undergraduate tuition rate (which covers about half of what it costs us to educate a student) is high relative to other higher education institutions. But, hand-in-hand with this high tuition is our generous undergraduate scholarship budget of $95M for AY15. We are one of six institutions in the nation that admits all students on a need-blind basis, awards all aid based on need, and meets full need each year.

The cost of educating a student is comparable across public and private research universities. The difference is that in the public sector, the state subsidizes this cost, whereas in the private sector, the subsidy comes from the institution.

In each case, the subsidy allows the institution to set tuition at a rate lower than the actual cost to educate the student. To parlay this into business terms, we sell a product for less than it costs us to make it. In our case, we subsidize our cost of educating an undergraduate, or for that matter a graduate student, with revenues generated from our annual endowment payout.

We could lower the tuition rate further by increasing our institutional subsidy. However, we prefer to set our tuition at a rate comparable to other private research universities and then grant further subsidies in the form of need-based scholarships to those demonstrating the inability to pay our “sticker price.”

The takeaway is that families paying the full “sticker price” are not subsidizing those who are unable to do this. All our students receive a generous subsidy from the endowment payout and some of them receive an additional subsidy to ensure their access and affordability.

In 2013-2014, we provided 75.9 percent of the total financial aid our undergraduates received, 92 percent of which was provided in the form of scholarships. From the students’ perspective, scholarships or grants – terms that are used interchangeably – are the sole forms of aid that unambiguously increase the financial accessibility and affordability of college, since they do not require repayment and do not increase the students’ indebtedness.

The primary form of undergraduate financial aid in the U.S. is student loans, and the primary source is the federal government. The preponderance of institutional scholarships at MIT is what sets us apart from most higher education institutions and should, in and of itself, secure us a position as one of the most affordable higher education institutions in the U.S.

Recent national initiatives are attempting to develop metrics that measure and then compare access and affordability across higher education. One metric, which is often used to measure an institution’s record of success in enrolling lower-income students, is the percent of Pell Grant recipients. And MIT ranks well here, with 18 percent of undergraduates receiving Pell Grants in 2013-2014. But this metric has limitations that are worth understanding.

The Pell Grant program is the second largest federal financial aid program after the Direct Stafford Loan program. Families making less than $60,000 annually may qualify. According to Sandy Baum, an economist who studies higher education pricing and financing, 80 percent of households earning less than $30,000 annually qualify for a Pell Grant, 60 percent from households earning between $30,000 and $50,000, and 44 percent from households in the $50,000 to $60,000 range.

| Back to top |

A better measure for access and affordability would be to capture all students below $60,000, not just the Pell Grant recipients, and in fact would probably include students just above that threshold, some of whom may be first-generation students. At MIT, about one-third of our students come from families with incomes under $75,000 and we ensure that they will receive sufficient scholarships to attend tuition-free.

The best metric to emerge for measuring and comparing affordability across institutions, and the standard that is most often used, is “net price.” The problem is that there is no consistent definition of net price, and some methodologies have more limitations than others.

Take for example the recent New York Times article, “Top Colleges That Enroll Rich, Middle Class and Poor.” The NYT chose to use the net price methodology used by the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) based on information it collects from higher education institutions through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) survey. Net price is most often defined as the difference between the total cost of attendance and scholarships and grants. In other words, it is what the family pays, including student loans and wages. But the IPEDS methodology does not include the full cost of attendance, as it excludes costs associated with personal expenses and travel. The methodology also excludes private scholarships when netting out scholarships and grants.

By their own admission, the NYT indicates that “Ideally, colleges would release a consistent set of net-price data, covering all students, in narrow income buckets.” That’s exactly what we do, and we believe our methodology is sounder. For us, “net price,” or what the family pays, is the difference between the total cost of attendance and all sources and forms of financial aid, including student loans and term-time employment. The reason we include student loans and employment is that, while they are less desirable forms of financial aid, their terms and conditions provide subsidies to students.

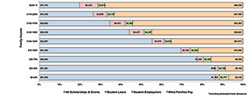

(click on image to enlarge)

The chart displays our 2013-2014 net price for families demonstrating financial need. We group families into $25K income bands up to $200K. Families earning more than $200K generally have more than one child in college at the same time. This chart provides families with a tool for understanding how families with comparable incomes are able to afford sending a child to MIT.

Has MIT solved the A2 problem? Is it a problem of perception, of reality, or both? There is a preponderance of evidence leading to the conclusion that we have: the income distribution of our undergraduate student body; our high admissions yield across all income ranges; the percent of first-generation and of Pell Grant recipients we enroll; our high retention and graduation rates; and our students’ low reliance on student debts. We may believe that this is compelling information. But access and affordability are “in the eyes of the beholder.” Ultimately, each family must decide for themselves whether MIT is affordable. In the meantime, we will continue to strive to find new and better ways to solve the A2 problem.

This article was originally published in the September 2014 DUE Newsletter.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |