| Vol.

XXXII No.

2 November / December 2019 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

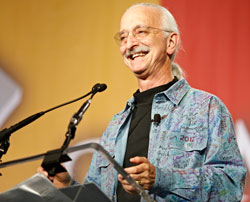

In Memoriam

Woodie Flowers

The following appeared in The Boston Globe on October 23, 2019.

Woodie Flowers, MIT robotics guru who championed ‘gracious professionalism,’ dies at 75

Woodie Flowers got his start in the field of robotics during a boyhood far removed from the MIT campus where he would become a beloved and inspirational professor.

“I grew up in a very small town in Louisiana,” he recalled in a 2014 interview posted on the flatlandkc.org website. “My first robot was a hot rod roadster and my father was my mentor. That was a wonderful introduction to engineering.”

Taking a cue from his always-inventive father, Dr. Flowers became a mentor to others to the umpteenth power: first when he popularized an engineering design class at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and later when he helped launch the FIRST Robotics Competition, which has since engaged the imagination of hundreds of thousands of high school students around the world.

Dr. Flowers, who was 75 and lived in Weston, died Oct. 11 after a brief illness.

He had been the Pappalardo professor emeritus of mechanical engineering, though no title could quite encompass his impact and presence at robotics competitions.

With a voice that never lost its Deep South beginnings, along with his mustache and longish hair that in later years he tied back in a gray ponytail, Dr. Flowers was a cheerleader and taskmaster who stressed the importance of individual accomplishment and of learning to work as part of a team.

Decades ago, he coined the term “gracious professionalism,” which he described as “a balance between the two sides of your brain.”

“If we were to super stereotype the brain’s behavior and say it has an empathetic or passionate side and a rational side, gracious professionalism is a blend of those two things,” he said in the 2014 interview. “I believe that’s where most of the population should be if they are to be considered a well-educated person.”

Engaging and charismatic, Dr. Flowers was as unforgettable as a professor in his famous class – initially called 2.70, and now 2.007 (Design and Manufacturing I) – as he was in other venues as a teacher and mentor.

“Woodie Flowers lived a life of impact,” Don Bossi, president of the nonprofit FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), said in a statement.

“Clearly a brilliant technical mind, he also embodied kindness and effortlessly communicated the inherent marriage of technology and humanity in everything he did,” Bossi said. “‘Gracious Professionalism,’ the ethos of FIRST which Woodie established early on, will live indefinitely through the millions of students he inspired through his words and actions.”

Early in his tenure motivating creativity, Dr. Flowers began instructing MIT students to build machines that could achieve a set task, such as in 1977’s “Thing of the Mountain,” when mini-robots raced to climb to the summit and get back down the other side of a pair of tilted ramps covered with sand.

“We try to pick problems in which the students have to make some visceral trade-offs,” he told the Globe that year. “They have to learn, in their guts, about having to give up one thing to gain another . . . as in giving up some speed to gain pushing power.”

Dr. Flowers extended his influence to the world stage upon joining with FIRST founder Dean Kamen to launch the FIRST Robotics Competition in 1992.

“Woodie Flowers is not only leaving behind a legacy of great work and important contributions to education and engineering, but more importantly, he leaves behind a legacy of kindness,” Kamen, who also invented the Segway, said in a statement.

“The things Woodie valued the most, he made sure to give back to the world,” Kamen added. “As someone who strived for graciousness in his every action, he urged the students he mentored to be kind and use their talents to do good.”

| Back to top |

Born in 1943, Woodie Claude Flowers (“It’s really on my birth certificate,” he told MIT’s The Tech in 2011) was named for his grandfathers – Woodie and Claude — and grew up in Jena, La.

He was the younger of two siblings whose parents were Abe Flowers and Bertie Graham. His mother was an elementary and special education teacher. His father was a welder and inventor, though he wasn’t quite as inventive with family finances.

We were literally dirt poor – never owned a house – but he did things in interesting and creative ways and I think I mimic him,” Dr. Flowers recalled in the Flatland interview.

Money was so tight that he thought college was beyond reach until a high school shop teacher arranged for a rehabilitation scholarship. Dr. Flowers had broken an arm as a boy, and the injury wasn’t set properly.

He graduated in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in engineering from Louisiana Tech University, where he met Margaret Weas. An education student, she initially stayed to finish a master’s at Louisiana Tech when he headed to MIT. They married in 1967 and she supported him through graduate work, switching from teaching to working in the computer field as they settled in Greater Boston.

From MIT, Dr. Flowers received a master’s in mechanical engineering, an engineering degree, and a doctorate, and as a graduate student he began designing prosthetics for above-knee amputees.

“He always wanted to learn,” Margaret said, and that continued into retirement.

They rose early to read together – “our 4 a.m. book club,” she said.

Interested in more than just a life of the mind, Dr. Flowers learned race car driving techniques in Watkins Glen, N.Y., and he took lessons on the trapeze and in hang-gliding and polo.

After he retired in 2007, “we thought, ‘Oh, he’s going to slow down,’ but he never did,” said his niece, Catherine Calabria of St. Augustine, Fla.

When Catherine bought a house, Dr. Flowers offered to help her build a table and found slabs of walnut and ash to craft into a one-of-a-kind piece of furniture, even though he hadn’t made one before.

“We treated it as a learning thing: ‘We’re going to learn a lot from this adventure,’” she said. “We just finished it two months ago.”

In addition to his wife and niece, Dr. Flowers leaves his sister, Kay Wells of St. Augustine.

FIRST, which is based in Manchester, N.H., and MIT will announce memorial gatherings to celebrate his life and legacy.

Along with teaching, Dr. Flowers hosted the national PBS series “Scientific American Frontiers” in the early 1990s and was awarded a regional Emmy.

He formerly was head of the system and design division in MIT’s department of mechanical engineering and had been FIRST’s Executive Advisory Board co-chair and distinguished adviser.

Dr. Flowers, who was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, counted among his many honors the Ruth and Joel Spira Outstanding Design Educator Award and the Edwin F. Church Medal, both from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Yet he always stressed the necessary duality of his “gracious professionalism” approach.

“I don’t believe we can afford to have people claim to have a liberal education without understanding the universe. I don’t believe we can afford to have large numbers of technologists and scientists who choose not to pay attention to humanism,” he said in the Flatland interview.

On that point, he was sure his legacy was secure.

“I believe that gracious professionalism is alive and well at MIT,” Dr. Flowers told The Tech.

Editor’s Note: Click here for an NBC tribute to Woodie.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |