Landscape Values and Social Acceptance

Consider:

What types of sites would be acceptable for urban wind turbines? Parks? Rivers? Shopping malls? Port areas? Industrial Sites?

“Attitudes towards wind power are fundamentally different from attitudes towards wind farms.”

“Decision-making on renewable power facilities does not usually include the most important discussion point for public stakeholders…”

Wolsink, Maarten. “Planning of renewables schemes: Deliberative and fair decision-making on landscape issues instead of reproachful accusations of non-cooperation.” 2007

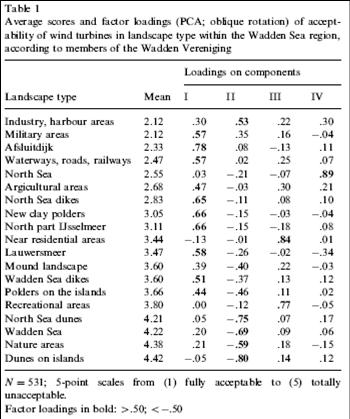

Locating wind turbines in cities raises new issues, though the literature does offer some suggestions of what can be expected. According to Maarten Wolsink, the acceptability of locations is tied very closely to fundamental cultural landscape values. In his words: “The visual evaluation of the impact of wind power on the values of the landscape is by far the most dominant factor in explaining why some are opposed to wind power implementation and why others support it…Even at the local level, direct environmental annoyance factors, of which noise is the most prominent, are dominated by the visual/landscape factor …Objections are mainly rooted in arguments concerning landscape characteristics and community identity.” [Table 1]

Table source: Wolsink 2007 (1)

Van Der Horst (2007) pursues a similar argument, stating that “Residents of stigmatised places are more likely to welcome facilities that are relatively ‘green’, while people who derive a more positive sense of identity from particular rural landscapes are likely to resist such potential developments, especially if they also live there.”

Though his discussion is centered on rural landscapes, his analysis of how certain locations are valued differently, both because of the previous use of the land and the characteristics of the present occupants is undoubtedly transferable to urban locations as well:

Use Value and Non-Use Value

“For some individuals some locations may have both use and non-use values. Such an overlap is more likely to occur in areas of higher landscape value…In the new rural economy the commodification of rural landscape, culture and lifestyle is more important than the physical exploitation of rural land. This relates not just to the expansion of tourism, but also to investment in rural areas through counterurbanisation and gentrification, often in pursuit of the ‘rural idyll’. In-migrants will subsequently act to protect their financial and emotional investment by opposing developments and activities that threaten the perceived

‘rurality of their new home’. In this way identity and material interest are collapsed together as a motivating force for political action.’’

Stigmatized Landscapes

“The existence of heavy industry and large(r) stacks in the area appears to make residents less likely to oppose the development of new plants … and more likely to support windfarms as an improvement of the image of the area. This is consistent with the literature on polluted and stigmatised places where efficacy is low … and this raises questions of environmental equity.”

Van der Horst, D. “Nimby or not? Exploring the relevance of location and the politics of voiced opinions in renewable energy siting controversies.” 2007

Sources:

1) Wolsink, Maarten. “Planning of renewables schemes: Deliberative and fair decision-making on landscape issues instead of reproachful accusations of non-cooperation.” Energy Policy. Kidlington: May 2007. Vol. 35, Iss. 5; p. 2692.

2) Van der Horst, Dan. “NIMBY or not? Exploring the relevance of location and the politics of voiced opinions in renewable energy siting controversies.” Energy Policy. Kidlington: May 2007. Vol. 35, Iss. 5; p. 2705.