Issues for Planners & Designers

California is far from being alone in its high wildfire threat. Many other western states, including Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Idaho, and Oregon, have experienced similar large fire events. In fact, ecosystems throughout the entire United States have been and continue to be shaped by fire.

If decision makers insist on allowing development to occur in wildfire prone areas, and people are willing to purchase homes there, it is important that planners and designers understand some of the basic mitigation techniques. Furthermore, people already living in these areas need to engage in ongoing maintenance of their property. This requires a certain level of education for all those involved in both writing and adhering to such regulations.

While there are many important ways that planners and designers can participate in reducing wildfire risks, the following highlights a few of the most important topics:

Other tools, such as mapping techniques, land use codes, comprehensive plans, and building codes are extremely invaluable in aiding planners, architects, resource managers, local fire officials, and other decision makers.-Ecosystem Management and Fire Ecology

-Subdivision Design and Layout

-Site Planning and Building Construction

Ecosystem Management & Fire Ecology

Source: http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/~joel/g148_f06/readings/cal_veg/cal_veg.html |

Understanding the ecosystem and the way fire behaves within that context is an important piece of approaching wildfires. For instance, Southern California’s ecosystem and climate make this is a unique area concerning wildfire threat. The combination of the Santa Ana winds, dry and hot temperatures in the autumn, and chaparral made the fires in 2003 and 2007 difficult, if not impossible, to control.

Plant communities differ in their levels of flammability. Chaparral scrublands of southern California ignite quite easily due to the level of dryness. Other plants which contain more moisture are generally more difficult to sustain flames. Flammability ratings are usually available through state forestry agencies and should be considered when landscape management plans are drawn up for a development. However, it is worth noting that introducing vegetation with higher moisture content usually means these plants are non-native and using up valuable water resources in an area that may otherwise not naturally sustain such vegetation.

Just as ecosystems react to fire in unique ways, fire itself behaves differently depending on what it’s burning (fuel type), how much there is of it (fuel load), how spread out the fuel sources are (fuel continuity), topography, and the area’s fire history. These factors will determine type of fire. Fires can crawl, jump, form a crown, or smolder. Knowing the basic science behind wildfire behavior can help decision makers make more appropriate decisions about development patterns and building design.

Subdivision Design and Layout

The following images illustrate different development patterns. In wildfire terms, these can be translated into variations of the wildland-urban interface (WUI).

Figure A: “Boundary” wildland-urban interface: Areas of development where homes, particularly new subdivisions, meet public or private wildlands, such as private or commercial forest land or public forests and parks. The boundary is clearly defined between suburban (or urban) and rural countryside.

Figure B: “Intermix” wildland-urban interface: Places where improved property and/ or structures are scattered and interspersed in wildland areas. These may be isolated rural homes or an area that is just beginning to go through the transition from rural to urban land uses.

Figure C: “Island” wildland-urban interface (also called “occluded” interface): Areas of wildland within predominantly urban or suburban areas. As cities or subdivisions grow, islands of undeveloped land may remain, creating remnant forests. Sometimes these remnants exist as parks, or as land that cannot be developed due to site limitations, such as wetlands.

Figure D: While these clusters exhibit partial characteristics of the above WUI types, the main feature is that they are close to a highway and there is a space between the dense vegetation and homes. From a wildfire perspective, these homes have both easy access for evacuation as well as firefighter capability. The vegetative clearing also reduces the likelihood of wildfire flames leaping onto roofs.

In addition to understanding how the development relates to the surrounding vegetation (which translates into the likelihood of a fire spreading to a house), each figure above also illustrates how subdivision design and layout relates to the surrounding infrastructure. Developments that are closer to major highways or arterials with multiple entrances and appropriate street widths allow both easier access for emergency vehicles and options for resident evacuation. When development is placed in steep terrain, and roads are narrow and difficult to navigate, fires may trap homeowners from escape by blocking the road. Similarly, fire fighters have a difficult time reaching these areas and vehicles place themselves in perilous driving situations. In sum, subdivision design and layout should consider proximity to vegetation, vehicular access, and the terrain as three key concepts.

Site Planning and Building Construction

There are two major factors when considering site planning and building construction: defensible space and roofing materials. While other aspects of planning and design are also important, these have been recognized as the best ways that a homeowner can protect his or her home from wildfire.

Defensible Space

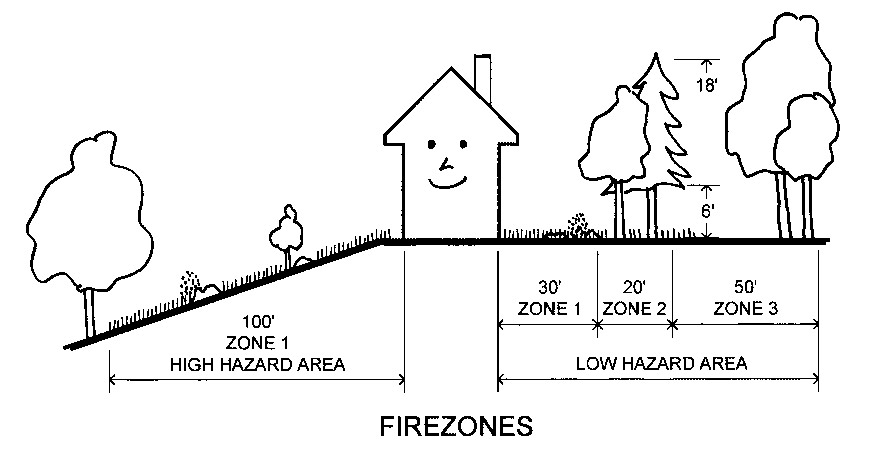

Defensible space is an area around a structure where fuels and vegetation are eliminated, treated, managed in such a way as to slow the spread of wildfire towards the structure. Creating defensible space also reduces the chance of a structure fire moving from a building to the surrounding forest. Defensible space is divided up into three different zones, with each zone having different considerations.

Source: http://www.firewise.org/resources/files/wildfr2.pdf

Zones will vary depending upon state or local regulations. The Firewise Communities program recommends that Zone 1 extends a minimum of 30 feet from a structure in a low hazard area. Plantings should be limited to properly spaced native species. In Zone 2, trees should be at least 10 feet apart, and all dead or dying limbs should be removed. In a low hazard area, Zone 2 should extend another 20 feet beyond Zone 1. Moderate and high hazard areas require that Zone 2 extend even further beyond Zone 1. This may range from 50 feet for moderate hazard areas to 200 feet for high hazard areas. Finally, Zone 3 should also be managed in the sense that highly flammable vegetation and dead or dying trees and shrubs are removed. The size of Zone 3 depends upon the level of wildfire risk and property boundaries.

For more general information on creating defensible space, please refer to Firewise Communities online resources.

For information specific to California, please refer to The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection General Guidelines for Creating Defensible Space.

Roofing Materials

Source: http://www.pagetrafficblog.com/google-maps-show-southern-californias-fire-information/3233/

Roofs are particularly vulnerable to wildfires due to their large surface area and exposure. In order to reduce wildfire risk, Class A or B roofing materials should be used, such as asphalt shingles, slate or clay tile, or metal. Roofs made out of wood should absolutely be avoided.

Sparks can also enter structures through vents. In order to avoid this, eaves should be enclosed with fire-resistive materials to deflect burning embers. Chimneys and stove pipers should be covered with a nonflammable screen. Similarly, exterior attic vents should also be covered with a metal wire mesh. The length or roof eaves should be limited so that they do not extend beyond exterior walls.

For more information about protecting homes from wildfires through construction design and materials, please refer to the Colorado State Forest Service website.