The 1842 Walhalla Ruhmes- und Ehrenhalle in Regensburg. [Photo by Michael J. Zirbes]

Valhalla

2014 March 17

SOURCE:

Einstein: Einblicke in seine Gedankenwelt --

Gemeinverständliche Betrachtegung über

die Relativitätstheorie und ein neues Weltsystem

entwickelt aus Gesprächen mit Einstein

von Alexander Moszkowski

[Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1921]

English translation:

Einstein the Searcher

translated by Henry L. Brose

[New York: E. P. Dutton, 1922], with a few additions and modifications.

Moszkowski's words are in bold.

Order of Distinction and Characteristics of Great Discoverers. ---

Galilei

and Newton. --- Forerunners and Priority. ---

Science and Religion. --- Inheritance of Talent. --- A

Dynasty of Scholars. ---

Alexander von Humboldt and

Goethe. --- Leonardo da Vinci. ---

Helmholtz. --- Robert Mayer and

Dühring. ---

Gauss and Riemann. --- Max Planck. ---

Maxwell and Faraday.

I HAD made up my mind to question Einstein about a

number of famous men, not concerning mere facts of

their lives and works, for these details were also procurable

elsewhere, and, moreover, I was not ignorant of them,

but what attracted me particularly was to try to discover how

the greatness of one might be compared with that of another.

This sometimes helps us to see a personality in a different light

and from a new perspective, which leads us to assign to him a

new position in the series of orders of merit.

I had really sketched out a list for this purpose, including

a great number of glorious names from the annals of physics

and regions just beyond : a table, as it were, from which one

might set up a directory for Valhalla ! It seemed to me a

pleasing thought to roam through this hall of celebrities in

company with Einstein, and to pause at the pedestal of the

busts of the great, who, in spite of their number, are still too

few, far too few, in comparison with the far too many who

populate the earth like so many factory-produced articles.

If we set to work to draw up a list of this sort, we soon find

that there is no end to these heroes of Valhalla, and we are

reminded of the hall of fame of the Northern Saga, of the

mythological Valhalla, whose ceiling was so high that the

gable was invisible, and whose extent was so great that anyone

wishing to enter could choose from five hundred and forty

entrances.

In reality our little excursion was far from taking these

dimensions, the chief reason being probably that we had

begun at Newton. However attractive it may be to hear

Einstein talk of Newton, a disadvantage arises in that we

find it hard to take leave of his bust situated at the main

portal, and that we continually revert to it even when we

call to mind the remaining paths free for our choice and

stretching out of sight.

Reality, even figuratively, offered a picture which differed

considerably from the measures of greatness apportioned

by legendary accounts. In Einstein's workroom, certainly,

a visitor encounters portraits, not busts, and it would be rash

to speak of this little collection of portraits as of a miniature

museum. No, it is certainly not that, for its catalogue

numbers only to three. But here they act as a trinity with a

special significance under the gaze of Einstein, who looks up

to them with reverence. To him their contribution of thought

is immeasurable :

FARADAY ;

MAXWELL with his rich coils of

hair ;

and between them, NEWTON with his flowing wig,

represented in an excellent English engraving, whose border

consists of symbolic insignias encircling his distinguished-looking

countenance.

[I have been thus far unable to locate any widely-circulated

engraving of Newton which exactly matches this description ;

those with borders of symbolic insignias for some reason

usually omit Newton's wig, and vice versa ! The nearest

I have found is a 1740 Dutch engraving by Houbraken which

may be viewed at the Royal Society's web-site, subject

to excessively legalistic "terms of use"; it shows the famous

Kneller portrait of Newton (bewigged) on an ornate pedestal

in front of what seems to be a pyramid. ]

According to Schopenhauer, the measure of reverence that

one can feel is a measure of one's own intrinsic value. Tell

me how much respect you can feel, and I shall tell you what

is your worth. It is certainly not necessary to emphasize

this quality specially in the case of Einstein, for there are other

points of vantage from which we may form an estimate of

his excellence. Nevertheless, I make special mention of the

circumstance to give an indication of the difference between a

revolutionary discoverer and revolutionary pioneers in other

fields.

It is particularly noticeable that inborn respect is

seldom found in modernists of Art. The only means of

propaganda known to them consists in a passionate denunciation

of what has been developed historically by gradual and patient

effort ; their retrospect consists of unmitigated contempt ;

they profess to be disciples only of what is most recent,

remaining confined within the narrow circle surrounding their

own ego. The horizon of the discoverer has a different radius.

He takes over responsibility for the future by never ceasing his

offerings at the altar of the Past.

There is probably no discoverer

who is devoid of this characteristic, but I should like

to emphasize that, among all the scientists with whom I am

acquainted, no one recognizes the merit of others so warmly

as Einstein. He becomes carried away with enthusiasm when

he talks of great men, or of such as appear great to him. His

Valhalla is not, of course, the same as that favoured by

Encyclopædias, and many a one whom we rank as a Sirius among

men is to be found dimmer

than the sixth order of magnitude

in Einstein's list. Nevertheless, his scientific heaven is

richly stocked,

and the reverence that was

originally inspired by reasoned thought has become infused

in his temperament and become a part of his emotional self.

One need only mention the name of Newton --- and even

this is scarcely necessary, for Newton seems always near at

hand ; if I happen to start with Descartes or Pascal, it does

not take long before we arrive at Newton. ANΔPA

MOI ENNEΠH !

Once we began with Laplace ; and it seemed almost as if the

Traité de la méchanique

céleste was to become the subject

of discussion. But Einstein left his seat, and, taking up a

position in front of his series of portraits on the wall, he

meditatively passed his hand through his hair, and declared :

"In my opinion the greatest creative geniuses are Galilei

and Newton, whom I regard in a certain sense as forming a

unity. And in this unity Newton is he who has achieved

the most imposing feat in the realm of science. These two

were the first to create a system of mechanics founded on a

few laws and giving a general theory of motions, the totality

of which represents the events of our world."

Interrupting his remarks, I asked : "Can Galilei's fundamental

law of inertia (Newton's First Law of Motion) be

said to be a law deduced from experience ? My reason for

asking is that the whole of natural science is a science of

experience, and not merely something based on speculation.

It might easily suggest itself to one that an elementary law

like that of linear motion could be derived from our everyday

experience. But, if this is the case, how is it that science

had to wait so long before this simple fact was discovered ?

Experience is as old as the hills ; why did the law of inertia

not make its appearance at the very beginning, when Nature

was first subjected to inquiry ? "

"By no means ! " replied Einstein. "The discovery of

the law of rectihnear motion of a body under no external

influences is not at all a result of experience. On the contrary !

A circle, too, is a simple line of motion, and has often been

proclaimed as such by predecessors of Newton, for example,

by Aristotle. It required the enormous power of abstraction

possessed only by a giant of reason to stabilize rectilinear

motion as the fundamental form."

To this may be added that before and even after the time

of Galilei, not only the circle but also other non-rectilinear lines

have been regarded even by serious thinkers (and

pseudo-thinkers) as the primary

lines given by Nature ; these thinkers even dared to apply

their curvilinear views to explaining world phenomena that

could be made clear only after Galilei's abstraction had been

accepted.

I asked whether the theory of gravitation was already

implicitly contained in Galilei's Laws of Falling Bodies.

Einstein's answer was in the negative : the gravitational theory

falls entirely to the credit of Newton, and the greatness of this

intellectual achievement remains unimpaired even if the efforts

of certain forerunners are recognized. He mentioned Robert

Hooke, whom, among others, Schopenhauer sets up against

Newton, with absolute injustice and from petty feelings of

antipathy, which takes its origin from Schopenhauer's

unmathematical type of mind. The vast difference between

Hooke's preliminary attempts at explaining gravitation, and

Newton's monumental structure, was beyond his power of

discernment.

Schopenhauer (

vol. ii. of the Parerga) uses two arguments

to discredit Newton. Firstly, he refers to two original works,

both of which he misinterprets ; secondly, he undertakes a

psychological analysis of Newton. He uses psychological

means, which would be about equally reasonable as applying

the Integral Calculus to proving facts of Ethical Psychology,

and he arrives at the conclusion that priority in discovering

the law of gravitation is due to some one else ; Hooke is pictured

as having been treated like Columbus : we now hear of

"America," and likewise "Newton's Gravitational System " !

Schopenhauer has, however, quite forgotten that he himself,

some pages earlier, trumpeted forth Newton's imperishable

fame with the words : "To form an estimate of the great

value of the gravitational system which was at least completed

and firmly established by Newton, we must remind ourselves

how entirely nonplussed about the origin of the motion of

celestial bodies thinkers had previously been for thousands of

years."

That bears the ring of truth. Newton's greatness

can be grasped only if thousands of years are used as a measure.

Whereas Schopenhauer argued from grounds drawn from

psychology and the principle of universal knowledge, his

antagonist Hegel, who was still more vague in these fields, sought to

dispense with both Newton and Kepler by calling to his aid

the so-called pure intuition of the curved line. In an

exposition

of truly comical prolixity, such as would have delighted the

hearts of scholiasts, he proves that the ellipse must represent

the fundamental type of planetary motion, this being quite

independent of Newton's laws, Kepler's observations, and resulting

mathematical relationships. And Hegel actually succeeds,

with a nebulous verbosity almost stultifying in its unmeaningness,

in paraphrasing Kepler's second law in his own fashion.

It reads like an extract from some carnival publication issued

by scientists in a bibulous mood to make fun of themselves.

But these extravagances, too, serve to add lustre to Newton,

for his genius shines out most brilliantly when it is a question of

expressing clearly, and without assumptions, a phenomenon of

cosmic motion. Here there are no forerunners, not even with

regard to his own law of gravitation. Newton showed with

truly triumphant logic that Kepler's second law belongs to

those things that are really self-evident.

This law, taken alone, offers considerable difficulties to

anyone who learns of it for the first time. Every planet

describes an ellipse ; that is accepted without demur. But the

uninitiated will possibly or even probably deduce from this

that the planet will pass over equal lengths of arc in equal

times. By no means, says Kepler ; the arcs traversed in equal

times are unequal. But if we connect every point of the

elliptic path with a definite point within the curve (the focus

of the ellipse) by means of straight lines, each of which is called

a radius vector, we get that the areas swept out by the radius

vector in equal times (and not the arcs) are equally great.

Why is this so ? This cannot be understood a priori. But

one might argue that since the attraction of the sun is the

governing force, this will probably have something to do with

Newton's law of gravitation, in particular with the inverse

square of the distance. And one might further infer that, if

a different principle of gravitation existed, Kepler's law would

assume a new form.

A fact amazing in its simplicity here comes to light.

Newton states the proposition : "According to whatever

law an accelerating force acts from a centre on a body moving

freely, the radius vector will always sweep out equal areas in

equal lengths of time."

Nothing is assumed except the law of inertia and a little

elementary mathematics, namely, the theorem that triangles

on the same base and of the same altitude are equal in area.

The form in which this theorem occurs in Newton's simple

drawing is certainly astonishing. One feels that there in a

few strokes a cosmic problem is solved ; the impression is

ineffaceable.

This theorem together with its proof is contained in

Newton's chief work, Philosophiæ naturalis

principia mathematica. The interfusion of philosophy and mathematics

furnished him with the natural principles of knowledge.

Einstein made some illuminating remarks about Newton's

famous phrase : "Hypotheses non fingo." I had said that

Newton must have been aware that it is impossible to build

up a science entirely free from hypotheses. Even geometry

itself has arrived at that critical stage at which Gauss and

Riemann discovered its hypothetical foundations.

Einstein replied : "Accentuate the words correctly and

the true sense will reveal itself ! " It is the last word that is

to be stressed and not the first. Newton did not want to feel

himself free from hypotheses, but rather from the assumption

that he invented them, except when this was absolutely

necessary. Newton, then, wished to express that he did not

go further back in his analysis of causes than was absolutely

inevitable.

Perhaps, I allowed myself to interject, a more violent

suspicion against the word "hypotheses" was prevalent with

scholars in Newton's time than now. Newton's emphatic

defence would then appear a shade more intelligible Or did

he cherish the belief that his world-law was the only possible

one in Nature ?

Einstein again referred to the universality of Newton's

genius, saying that Newton was doubtless aware of the

range within which his law was valid : this law applies to the

realm of observation and experience, but is not given a priori,

no more than Galilei's Law of Inertia. It is certainly conceivable

that beyond the domain of human experience there

may be an undiscoverable universe in which a different fundamental

law holds, and one which, nevertheless, does not contradict

the principle of sufficient reason.

The antithesis : Simplicity --- Complexity, led the conversation

into a short bypath ; it arose out of an example which

I quoted and that I shall repeat here even if it may seem

irrelevant.

One might well expect that just as for attraction there

must be a general law for resistance or repulsion. And if

attraction occurs according to the inverse square of the

distance, then it would be an extremely interesting parallel if

a similar law were to hold for repulsion except that the

proportionality were direct instead of inverse. There have

actually been physicists who have proclaimed a direct square

law of repulsion ; I have heard it in lectures myself. The

action of a resisting medium, as, for example, the resistance of

the air to the flight of a cannon-ball, is stated to be proportional

to the square of the velocity of the projectile.

This theorem is wrong. If it were correct, and verified by

experiment, we should have to regard it as being presumably

the only possible and directly evident form of the law of

repulsion or resistance. There would, at least, be no logical

reason for contradicting it.

But here we have "an impure relationship," as Einstein calls it ---

that is, we are unable to express an exact connexion between

the velocity of a body in flight and the air resistance.

This fallacious assumption by no means proceeded from

illogical reasoning, and it seemed to rest on a sound physical

basis. For, so it was argued, if the velocity is doubled, there

is twice as much air to be displaced, so that the resistance will

be four times as great. But this was contradicted outright by

experimental evidence. One cannot even call it an approximate

law, except for very low speeds. For greater speeds

we find, instead of a quadratic relation, a cubical one, or one

of a more complex nature.

Photographs have demonstrated

that the resistance experienced by a projectile in flight is due

to the excitation of a powerful central wave, to the friction

between the air and the surface of the projectile, and to eddies

produced behind the projectile --- that is, to various conjoined

factors, each of which follows a different law, and such that

the combined effect cannot be expressed by a simple formula

at all. This phenomenon is thus very complicated and offers

almost insuperable difficulties to analysis. A beautiful

remark was once made, which characterizes such events in

Nature.

During a conversation with Laplace, Fresnel said that

Nature does not worry about analytical difficulties. There

is nothing simpler than Newton's Law in spite of the

complicated nature of planetary motions. "Nature here

despises our analytical difficulties," said Fresnel ; "she applies

simple means, and then by combining them produces an almost

inextricable net of confusion. Simplicity lies concealed in

this chaos, and it is only for us to discover it ! " But this

simplicity when it is discovered is not always found to be

expressible in simple formulae, nor must it be forgotten that

even the ultimate discoverable simplicity points to certain

hypothetical assumptions.

"Hypotheses non fingo ! " This phrase of Newton's

remains true, if we maintain Einstein's interpretation : "He

did not wish to go further back in his analysis of causes than

was absolutely inevitable." It interested me to pursue this

line of thought suggested by Einstein still further, and I

discovered that these words of Newton had actually been

falsely accentuated and hence misinterpreted by many

authorities on science. Even Mill and the great scholar,

William Whewell, succumbed to this misunderstanding.

Credit must be given to a more modem scholar, Professor

Vaihinger of Halle, for being sufficiently keen of hearing to

detect the true accentuation ; and now that Einstein has

corroborated fully this explanation, doubts as to the true

sense of the words are no longer to be feared.

[See Die Philosophie des Als Ob by

Hans Vaihinger (1922), page 57.]

The trend of our talk brought us to a discussion of the

conception, "law of nature." Einstein recalled Mach's

remarks, and indicated that the point was to determine how

much we read out of Nature ; and these observations made at

least one thing clear, namely, that every law signifies some

limitation ; in the case of human laws, expressed in the civil

and penal code, the limitation affects the will, and possible

actions, whereas natural laws signify the limitations which we,

taught by experience, prescribe to our expectations.

Nevertheless, the conception remains elastic, for the question will

always intrude itself : What does prescription mean ? Who

prescribes ? Kant has assigned to Man the foremost position

inasmuch as it is he who is regarded by Kant as prescribing

laws to Nature. Bacon of Verulam [

Novum Organum: Aphorisms I.3]

emphasizes the ambiguous

point of view by asserting : "Natura non vincitur nisi parendo,"

Man conquers Nature only by obeying her, that is, by conforming

to her immanent norms. Thus the laws exist without

us, and we have only to discover them. When they have been

found, Man can react by applying them to subdue Nature.

Man becomes the dictator and dictates to Nature the laws

according to which she for her part has to subjugate mankind.

Whether we adopt the one view or the other, there is a vicious

circle, from which there is no escape. A law is a creation of

intellect, and

Mephisto's words remain true : "In the end we

depend on the creatures of our own making ! "

In Newton's soul, obedience and the wish to obey must

have been pre-eminent traits. Is he not reputed to have

been pious and strong of faith ?

Einstein confirmed this, and, raising his voice, he generalized

from it, saying : "In every true searcher of Nature there is a

kind of religious reverence ; for he finds it impossible to

imagine that he is the first to have thought out the exceedingly

delicate threads that connect his perceptions. The aspect

of knowledge which has not yet been laid bare gives the

investigator a feeling akin to that experienced by a child who

seeks to grasp the masterly way in which elders manipulate

things."

This explanation implied a personal confession. For he

had spoken of the childlike longing felt by all, and had

interpreted the subtle intricacies of the scientist's ideas in

particular as springing from a religious source. Not all have

confessed this ; we know, indeed, that the convictions of

many a one were not so. Let us cling to the fact that the

greatest in the realm of science --- Newton, Descartes, Gauss,

and Helmholtz --- were pious, although their faith varied in

degree. And let us not forget that the most bitter opponent

of this attitude of mind, the originator of "Ecrasez l'infame,"

finally had a temple built bearing the inscription : "Deo

erexit Voltaire."

In Newton positivism found its most faithful disciple, and

his research was directly affected by his religious attitude. He,

himself, was the author of that beautiful thought : "A limited

measure of knowledge takes us away from God ; an increased

measure of knowledge takes us back to Him." It was he who

considered that the world-machine that he had disclosed was

not sufficiently stabilized by his mathematical law, and so he

enlisted the intermittent help of an assistant for the Creator,

Concursus Dei, to attend to the functioning of the machine.

Finally, he slipped from the path of naive faith onto theological

bypaths and wrote devout essays on apocalyptic matters.

On the other hand, Descartes' piety, which was genuine at root,

exhibited suspicious offshoots, and one cannot shake off the

feeling that he was smiling up his sleeve when he was making

some of his solemn declarations. He was a master of compromise,

and gave due expression to its spirit, which F. A.

Lange bluntly stated was merely a veil for "Cowardice

towards the Church." Voltaire, an apostle of Newton's

system of natural philosophy, went so far in his condemnation

of Descartes' confession of faith that he affirmed: "The

Cartesian doctrine has been mainly instrumental in persuading

many not to recognize a God."

As Einstein had called special attention to the childlike

nature of the scientist's root-impulse, I quoted a remark of

Newton that seemed to me at the moment to be a confirmation

of Einstein's attitude :

"I do not know what I may appear to the world, but

to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on

the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a

smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary,

whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before

me." Are we not to regard this analogy of Newton's as being

intended to convey a religious meaning ?

"There is no objection to this," said Einstein, "although

it seems to me more probable that, in saying this, Newton set

down the view only of the pure investigator. The essential

purpose of his remarks was to express how small is the range

of the attainable compared with the infinite expanse offered

for research."

Through some unexpected phrase that was dropped, the

conversation took a new turn at this point, which I should

not like to withhold, inasmuch as it gave rise to a noteworthy

observation of Einstein about the nature of genius. We were

talking about the "possibility of genius for science being

inherited" and about the comparative rareness with which

it occurs. There seems to have been only one case of a real

dynasty of great minds, that of the ten Bernoullis who were

descended of a line of mathematicians, and all of them achieved

important results, some of them making extraordinary

discoveries. Why is this exception unique ? In other examples

we do not get beyond three or four names in the same family,

even if we take Science and Art conjointly. There were two

Plinys, two Galileis, two Herschels, two Humboldts, two

Lippis, two Dumas, several Bachs, Pisanos, Robbias, and

Holbeins --- the net result is very poor, even if we count similar

names, disregarding the fact of relationship ; there is no

recognizable dynasty except in the case of the ten Bernoullis.

(The Roman family Cosmati, of the thirteenth century, which gave us

seven splendid representatives of architecture and mosaic work, hardly comes

into consideration, since not one of them is regarded in the history of art as

a real genius.)

"And so," I continued, "the conclusion seems justified that

Nature has nothing to do with a genealogy of talents, and

that, if we happen to notice manifestations of talent in one

and the same family, this is a mere play of chance."

Einstein, however, contradicted this emphatically :

"Inherited talent certainly occurs in many cases,

where we do not

observe it, for genius in itself and the possibility of genius

being apprehended are certainly far from always appearing in

conjunction. There are only insignificant differences between

the genius that expresses itself in remarkable achievements and

the genius that is latent. At a certain instant, perhaps, only

some impulse was wanting for the latent genius to burst forth

with all clearness and brilliance ; or, perhaps, it required only

an unusual situation in the development of science to call

into action his special talents, and thus it remained dormant,

whereas a very slight change of circumstances would have

caused them to assert themselves in definite results.

"In passing I should like to remark that you just now

mentioned the two Humboldts ; it seems to me that Alexander

von Humboldt, at least, is not to be counted as a genius. It

has struck me repeatedly that you pronounced his name with

particular reverence --- "

"And I have observed equally often, Professor, that you

made a sign of disapproval. For this reason slight doubts

have gradually been rising in me. But it is difficult to get free

from the orders of greatness that one has recognized for

decades. In my youth people spoke of a Humboldt just

as we speak of a Cæsar or a Michelangelo, to denote

some pinnacle of unrivalled height. To me at that time

Humboldt's Kosmos

was the Bible of Natural Science, and

probably such memories have a certain after-effect."

"That is easy to understand," said Einstein. "But we

must make it clear to ourselves that for us of the present day

Humboldt scarcely comes into consideration when we direct

our gaze on to the great seers. Or, let us say more clearly,

he does not belong to this category. I certainly grant him

his immense knowledge and his admirable faculty of getting

into touch with the unity of Nature, which reminds us of

Goethe."

"Yes ; this feeling for the uniformity of the cosmos had

probably persuaded me in his favour," I answered, "and I am

glad that you draw a parallel with Goethe in this respect. It

reminds me of Heine's story : If God had created the whole

world, except the trees and the birds, and had said to Goethe :

My dear Goethe, I leave it to you to complete this work,

Goethe would have solved the problem correctly and in a

God-like manner --- that is, he would have painted the trees green

and given the birds feathers.

"Humboldt could equally well have been entrusted with

this task. But various objections may be raised against such

reflections of a playful poetic character . . . one objection

being that Goethe's own knowledge of ornithology was

exceedingly limited. Even when nearly eighty he could not

distinguish a lark from a yellow-hammer or a sparrow ! "

"Is that a fact ? "

"Fully confirmed ! Eckermann gives a

detailed report of

it in a conversation which took place in 1827. As I happened

to come across the passage only yesterday, I can quote the

exact words if you will allow me : Great and good man,

thought Eckermann, who hast explored Nature as few have

ever done, in ornithology thou seemest still a child !"

For a speculative philosopher, it may here be interposed,

this might well serve as the starting-point of an attractive

investigation. Goethe, on the one hand, cannot recognize a

lark, but would have been able to grasp the Platonic idea

of the feathered species, even if there had been no such things

as birds : Humboldt, on the other hand, would perhaps have

been able to create the revolving planets, if Heaven had

commanded it ; but he would never have succeeded in becoming

the author of what we call an astronomical achievement,

such as that of Copernicus or of Kepler.

[This discussion of an anecdote by Heine

that would have been familiar to most German readers is

perhaps meant by Moszkowski,

Einstein's personal Eckermann, as some

kind of self-deprecating joke. In Chapter 26 of his

Italian Travel Sketches, Heine ridicules

Eckermann as Goethe's "parrot", attributing to him the story about

Goethe completing God's creation and adding, "Some truth lies in these

words, and I am indeed of opinion that Goethe would occasionally

have managed his part better than the good God himself ; for instance,

he would have created Herr Eckermann much more completely ---

that is to say, with feathers ..." The anecdote about God is in fact

a very loose paraphrase -- or rather parody -- of

some remarks on Goethe's genius in Eckermann's early

philosophical work

Beiträge zur Poesie [Stuttgart: Cotta, 1824].]

And with reference to certain other men I elicited from

Einstein utterances that reduced somewhat my estimate of

their importance.

We were speaking of Leonardo da Vinci, omitting all

reference to his significance in the world of Art --- that is, only

of Leonardo the Scholar and the Searcher. Einstein is far

from disputing his place in the Valhalla of great minds, but

it was clear that he wished to recommend a re-numbering of

my list, so that the Italian master would not occupy a position

in just the first rank.

The problem of Leonardo excited great interest in me,

and it deserves the consideration of every one. The further

the examination of his writings advances, the more does this

problem resolve itself into the question : How much altogether

does modern science owe to Leonardo ? Nowadays it is

declared in all earnestness that he was a painter and a sculptor

only by the way, that his chief profession was that of an

engineer, and that he was the greatest engineer of all times.

This has in turn given rise to the opinion that, as a scientist,

he is the light of all ages, and in the abundance of his

discoveries he has never been surpassed before or after his own

time.

As this question had arisen once before, I had come

equipped with a little table of facts, hastily drawn from special

works to which I had access. According to my scheme,

Leonardo was the true discoverer and author of the following

things :

This list aroused great distrust in Einstein : he regarded

it as the outcome of an inquisitive search for sources, excusable

historically, but leading to misrepresentation. We are falsely

led to regard slightly related beginnings, vague tracks, hazy

indications, which are found, as evidences of a real insight

which disposes us to "elevate one above all others." Hence

a mythological process results, comparable to that which, in

former times, thrust all conceivable feats of strength onto

one Hercules.

I learned that recently a strong reaction has asserted

itself in scientific circles against this one-sided hero-worship ;

its purpose is to reduce Leonardo's merits to their proper

measure. Einstein made it quite clear that he was certainly

not to be found on the side of the ultra-Leonardists.

It cannot be denied that the latter have valuable arguments

to support their case, and that these arguments become

multiplied in proportion as the publication of Leonardo's

writings (in the Codex Atlanticus, etc.), which are so difficult to

decipher, proceeds. The partisans of Leonardo derive considerable

support in many points from recognized authorities, as

in the case of Cantor, the author of the monumental history

of mathematics. We there

read : "The greatest Italian

painter of the fifteenth century was not less great as a scientist.

In the history of science his name is famous and his

achievements are extolled, particularly those which give him a claim

to be regarded as one of the founders of Optics." He is

placed on a level with

Regiomantus as one of the chief builders

of mathematics of that time. Nevertheless, Cantor raises

certain doubts by remarking that the results of investigations

made up to the present do not prove Leonardo to be a great

mathematician. On another page he is proclaimed simultaneously

with Archimedes and Pappus as a pioneer of the doctrines

of the centre of gravity.

With regard to the main points, Leonardo's priority in

the case of the Laws of Falling Bodies, the Theory of

Wave-motion, and the other fundamental principles of physics,

Einstein has the conviction that the partisans of Leonardo

are either mistaken in the facts or that they overlook forerunners.

In the case of these principles, above all, there is

always some predecessor, and it is almost impossible to trace

the line of discoveries back to the first source. Just as writers

have wished to deprive Galilei, Kepler, and Newton of their

laurels in favour of Leonardo, so the same might be done with

Copernicus.

This has actually been attempted. The real Copernicus,

so one reads, was Hipparchus of Nicæa, and if we go back

still further, a hundred years earlier, two thousand years ago,

we find that Aristarchus of Samos taught that the world

rotated about its own axis and revolved round the sun.

And we need not even stop there, in Einstein's opinion.

For it is open to conjecture that Aristarchus in his turn has

drawn on Egyptian sources. This retrogressive investigation

may excite the interest of archæologists, and in particular

cases perhaps lead to the discovery of a primary claim to

authorship, but it cannot fail to excite suspicion against the

conscious intention of conferring all the honours of science

on an individual discoverer. Leonardo's superlative constructive

genius is not attacked in these remarks, and there

seems no reason for objecting if anyone wishes to call him

the most ingenious engineer of all times.

All the pressures and tensions occurring in Nature seemed

to be repeated in him as "inner virtues," an expression

borrowed from Helmholtz, who used it with reference to

himself. This analogy might be extended by saying that,

in the works of both, Man himself with his organic functions

and requirements plays an important role. For them the

abstract was a means of arriving at what was perceptual,

physiologically useful, and stimulating in its effect on life.

Leonardo started out from Art, and throughout the realm

of mechanics and machines he remained an artist in method.

Helmholtz set out from the medical side of physiology and

transferred the valuations of beauty derived from the senses

to his pictures of mechanical relationships. The life-work

of each has an æsthetic colouring, Leonardo's being of a

gloomy hue, that of Helmholtz exhibiting brighter and happier

tints. Common to both is an almost inconceivable versatility

and an inexhaustible productivity.

Whenever Einstein talks of Helmholtz he begins in warm

terms of appreciation, which tend to become cooler in the

course of the conversation. I cannot quote his exact words,

and as I cannot thus give a complete account for which full

responsibility may be taken, it may be allowable to offer a

few important fragments that I have gathered.

Judged by the average of his accomplishments, Helmholtz

is regarded by Einstein as an imposing figure whose fame in

later times is assured ; Helmholtz himself tasted of this

immortality while still alive. But when efforts are made to rank

him with great thinkers of the calibre of Newton, Einstein

considers that this estimate cannot be fully borne out. In

spite of all the excellence, subtlety, and effectiveness of

Helmholtz's astoundingly varied inspirations, Einstein seems to fail

to discover in him the source of a really great intellectual

achievement.

At a Science Congress held in Paris in 1867, at which Helmholtz

was present, a colleague of his was greeted with unanimous

applause when he toasted him with the words : "L'ophthalmologie

était dans les ténèbres, --- Dieu parla,

que Helmholtz naquit --- Et la lumière était faite !"

It was an almost exact

paraphrase of the

homage which Pope once addressed to

Newton. At that time the words of the toast were re-echoed

throughout the world ; ophthalmology was enlarged to science

generally, and the apotheosis was applied universally. Du

Bois-Reymond declared that no other nation had in its scientific

literature a book that could be compared with Helmholtz's

works on

Physiological Optics and on

Sensations of Tone.

Helmholtz was regarded as a god, and there are not a few to

whom he still appears crowned with this divine halo.

A shrill voice pierced the serene atmosphere, attacking one

of his main achievements. The dissentient was Eugen Dühring,

to whose essay on the Principles of Mechanics

[Kritische Geschichte der allgemeinen

Principien der Mechanik, Leipzig, 1877]

a coveted

prize was awarded, a fact which seemed to stamp him as being

specially authorized to be a judge of pre-eminent achievements

in this sphere. Dühring's aim was to dislodge one of the fundamental

supports of Helmholtz's reputation by attacking his

"Law of the Conservation of Energy." If this assault

proved successful, the god would lie shattered at his own

pedestal.

Dühring, indeed, used every means to bespatter his fair

name in science ; and it is hardly necessary to remark that

Einstein abhors this kind of polemic. What is more, he

regards it as a pathological symptom, and has only a smile of

disdain for many of Dühring's pithy sayings. He regards

them as documents of unconscious humour to be preserved

in the archives of science as warnings against future repetitions

of such methods.

Dühring belonged also to those who wished to exalt one

above all others. He raised

an altar to Robert Mayer, and

offered up sanguinary sacrifices. Accustomed to doing his

work thoroughly, he did not stop at Helmholtz in choosing

his victims. No hecatomb seemed to him too great to do

honour to the discoverer of the Mechanical Equivalent of

Heat, and so his next prey was Gauss and Riemann.

Gauss and Riemann ! Each was a giant in Einstein's opinion.

He knew well that this raging Ajax had also made an assault

against them, but he had no longer a clear recollection of the

detailed circumstances ; as the references were near at hand,

he allowed me to repeat a few lines of this tragi-comedy.

Helmholtz, according to Dühring (who also calls him

"Helmklotz"), has done no more than distort Mayer's fundamental

mechanical idea, and interpret it falsely. By "philosophizing" over it,

he has completely spoilt it, and rendered

it absurd. It was the greatest of all humiliations practised

on Mayer that his name had been coupled with that of one

whom he had easily out-distanced, and whose clumsy attempts

at being a physicist were even worse than those by which he

sought to establish himself as a philosopher.

The offences of Gauss and Riemann against Mayer are

shrouded in darkness. But there was another would-be

scientist, Justus von Liebig, who, being opposed to Mayer,

aroused the suspicions of Dühring, particularly as he had used

his "brazen-tongue" to defend the two renowned mathematicians.

After he, and Clausius too, had been brought to

earth, Dühring launched out against the giants of

Göttingen.

In the chapter on Gauss and "Gauss-worship," we read :

"His megalomania rendered it impossible for him to take

exception to any tricks that the deficient parts of his own

brain played on him, particularly in the realm of geometry.

Thus he arrived at a pretentiously mystical denial of Euclid's

axioms and theorems, and proceeded to set up the foundations

of an apocalyptic geometry not only of nonsense but of

absolute stupidity. . . . They are abortive products of the

deranged mind of a mathematical professor, whose mania for

greatness proclaims them as new and superhuman truths ! . . .

The mathematical delusions and deranged ideas in question

are the fruits of a veritable paranoia geometrica."

After Herostratus [an arsonist motivated

by the desire to go down in history]

had burnt to ashes the consecrated

temple, the Ionian cities issued a proclamation that his name

was to be condemned to perpetual oblivion ! The iconoclast

[Tempel-Attentäter]

Dühring is immortalized, for, apart from the charge of arson,

he is notable in himself. In his case we found ourselves

confronted with unfathomable problems of a scholar's complex

nature, problems which even a searcher like Einstein failed to

solve. The simplest solution would be to turn the tables and

to apply the term "paranoia" as a criticism to the book on

Robert Mayer, and thus demolish it. But this will not do,

for if we merely pass over the pages of distorted thought,

we are still left with a considerable quantity of valuable

material.

Does Dühring, after all, himself deserve a place in our

Valhalla ? The question seems monstrous, and yet cannot

be directly answered in the negative. The individual is to

be judged according to his greatest achievement, and not

according to his aberrations. The works of Aristotle teem

with nonsensical utterances, and Leonardo's

Bestiarius is an

orgy of abstruse concoctions. If Dühring had written nothing

beyond his studies of personalities ranging from Archimedes

to Lagrange, the portals would yet have been open to him.

Even in his eulogy of Robert Mayer, which is besmirched

with unseemly remarks, he displays at least the courage of his

convictions.

[The blind philosopher and

social scientist Eugen Dühring,

little remembered today,

was a towering, wrathful figure looming

large in his era's

intellectual life. Irascible and combative, a

fervent nationalist, a convinced materialist,

equally virulent in his antisemitism, his anti-Christianity,

his anti-Darwinism, his anti-capitalism, and

his anti-Marxism, the archenemy of Friedrich Engels

was one of those regrettably

numerous Nineteenth Century German

thinkers who in retrospect are hard to see

as anything but forerunners of Nazism ;

certainly his remarks quoted above

anticipate what the "Aryan Physicists"

of the 1930s would say about Einstein !

However Dühring's political theory, a

kind of Romantic

socialism, was more anarchist than fascist.

Physics was one of his (numerous) major

interests. He was still alive in 1919, but

died around the time Moszkowski's

book was published.]

The attempt at a comparison between Robert Mayer and

Helmholtz is doomed to failure even when considered

dispassionately, inasmuch as the disturbing factor of priority here

intrudes itself. The definite fixing of the Law of Energy is

certainly to the credit of Helmholtz, but perhaps he would have

gained by laying more stress on the discovery of it five years

earlier by the doctor in Heilbronn. And again, this would

not have been final, for the invariance of the sum of energy

during mechanical actions was known even by Huyghens.

The Heilbronn doctor performed one act of genius in his life,

whereas Helmholtz during his whole life moved asymptotically

to the line of genius without ever reaching it.

If my interpretation

of Einstein's opinion is correct, Helmholtz is to be

credited with having the splendour of an overpowering gift

for research predominant in his nature, but is not necessarily

to be given a seat among the most illustrious of his branch of

science. Einstein wishes to preserve a certain line of demarcation

between this type and not only the Titans of the past,

but also those of the present. When he speaks of the latter,

his tone becomes warmer. He does not need circuitous

expressions, each syllable rings with praise. He has in

mind, above all, Hendrik Antoon Lorentz in Leyden, Max

Planck, and Niels Bohr ; we then see that he feels Valhalla

about him.

The reason that I have tried to maintain the metaphor of

a Temple of Fame is due to an echo of Einstein's own words

at a celebration held in honour of the sixtieth birthday of

the physicist Planck in the May of 1918. This speech created

the impression of a happy harmony resulting from a fusion

of two melodies, one springing from the intellect, the other

rising from the heart. We were standing as at the Propylons

with a new Heraclitus uttering the cry : Introite, nam et hie

dii sunt!

I should like to give the gist of this beautiful address in

an extract uninterrupted by commentaries.

"The Temple of Science" --- so Einstein

began --- "is a

complex structure of many parts. Not only are the inmates

diverse in nature, but so also are the inner forces that they

have introduced into the temple. Many a one among them

is engaged in Science with a happy feeling of a superior mind,

and finds Science the sport which is congenial to him, and

which is to give him an outlet for his strong life-forces, and to

bring him the realization of his ambitions. There are, indeed,

many, too, who offer up their sacrifice of brain-matter only

in the cause of useful achievements. If now an angel of heaven

were to come and expel all from the temple who belonged to

these two categories, a considerable reduction would result,

but there would still remain within the temple men of present

and former times : among these we count our Planck, and

that is why he has our warm affection.

"I know full well that, in doing this, we have light-heartedly

caused many to be driven out who contributed much to the

building of the temple ; in many cases our angel would find

a decision difficult. . . . But let us fix our gaze on those

who find full favour with him ! Most of them are peculiar,

reserved, and lonely men, who, in spite of what they have

in common, are really less alike than those who have been

expelled. What led them into the temple ? . . .

"In the first

place, I agree with Schopenhauer that one of the most powerful

motives that attract people to Science and Art is the longing

to escape from everyday life with its painful coarseness and

unconsoling barrenness, and to break the fetters of their own

ever-changing desires. It drives those of keener sensibility

out of their personal existence into the world of objective

perception and understanding. This motive force is similar

to the longing which makes the city-dweller leave his noisy,

confused surroundings and draws him with irresistible force to

restful Alpine heights, where his gaze covers the wide expanse

lying peacefully before him on all sides, and softly passes

over the motionless outlines that seem created for all eternity.

"Associated with this negative motive is a positive one, by

virtue of which Man seeks to form a simplified synoptical

view of the world in a manner conformable to his own nature,

in order to overcome the world of experience by replacing it,

to a certain degree, by this picture. This is what the painter

does, as also the poet, the speculative philosopher, and the

research scientist, each in his own way. He transfers the

centre of his emotional existence into this picture, in order

to find a sure haven of peace, one such as is not offered in the

narrow limits of turbulent personal experience.

"What position does the world-picture of the theoretical

physicist occupy among all those that are possible ? He

demands the greatest rigour and accuracy in his representation,

such as can be gained only by using the language of mathematics.

But for this very reason the physicist has to be more

modest than others in his choice of material, and must confine

himself to the simplest events of the empirical world, since

all the more complex events cannot be traced by the human

mind with that refined exactness and logical sequence which

the physicist demands. ... Is the result of such a restricted

effort worthy of the proud name world-picture ?

"I believe this distinction is well deserved, for the most

general laws on which the system of ideas set up by theoretical

physics is founded claim to be valid for every kind of natural

phenomenon. From them it should be possible by means of

pure deduction to find the picture, that is, the theory, of every

natural process, including those of living organism, provided

that this process of deduction does not exceed the powers

of human thought. Thus there is no fundamental reason

why the physical picture of the world should fall short of

perfection. . . .

"Evolution has shown that among all conceivable

theoretical constructions there is, at each period,

one which shows itself to be superior to all

others, and that the world of

perception determines in practice the theoretical system,

although there is no logical road from perception to the

axioms of the theory, but rather that we are led towards

the latter by our intuition, which establishes contact with

experience. . . .

"The longing to discover the pre-established harmony

recognized by Leibniz is the source of the inexhaustible patience

with which we see Planck devoting himself to the general

problems of our science, refusing to allow himself to be

distracted by more grateful and more easily attainable objects. . . .

The emotional condition which fits him for his task is akin

to that of a devotee or a lover ; his daily striving is not the

result of a definite purpose or a programme of action, but

of a direct need. . . . May his love for Science grace his

future course of life, and lead him to a solution of that

all-important problem of the day which he himself propounded,

and to an understanding of which he has contributed so

much ! May he succeed in combining the Quantum Theory

with Electrodynamics and Mechanics in a logically complete

system ! "

"What grips me most in your address," I said, "is that

it simultaneously surveys the whole horizon of science in

every direction, and traces back the longing for knowledge

to its root in emotion. When your speech was concluded,

I regretted only one thing --- that it had ended so soon.

Fortunate is he who may study the text."

"Do you attach any importance to it ?" asked Einstein ;

"then accept this manuscript." It is due to this act of

generosity that I have been able to adorn the foregoing

description of the excursion into Valhalla with such a valuable

supplement.

The conversation had begun with the brilliant constellation

Galilei-Newton, and near the end inclined again towards

the consideration of a double-star : the names of Faraday

and Maxwell presented themselves.

"Both pairs," Einstein declared, "are of the same magnitude.

I regard them as fundamentally equal in their services

in the onward march of knowledge."

"Should we not have to add Heinrich Hertz as a third

in this bond ? This assistant of Helmholtz is surely regarded

as one of the founders of the Electromagnetic Theory of Light,

and we often hear their names coupled, as in the case of the

Maxwell-Hertz equations."

"Doubtless," replied Einstein, "Hertz, who is often

mentioned together with Maxwell, has an important rank

and must be placed very high in the world of experimental

physics, yet, as regards the influence of his scientific personality,

he cannot be classed with the others we have named. Let

us, then, confine ourselves to the twin geniuses Faraday and

Maxwell, whose intellectual achievement may be summarized

in a few words. Classical mechanics referred all phenomena,

electrical as well as mechanical, to the direct action of particles

on one another, irrespective of their distances from one

another. The simplest law of this kind is Newton's expression

: Attraction equals Mass times Mass divided by the

square of the distance. In contradistinction to this, Faraday

and Maxwell have introduced an entirely new kind of physical

realities, namely, fields of force. The introduction of these new

realities gives us the enormous advantage that, in the first

place, the conception of action at a distance, which is contrary

to our everyday experience, is made unnecessary, inasmuch

as the fields are superimposed in space from point to point

without a break ; in the second place, the laws for the field,

especially in the case of electricity, assume a much simpler

form than if no field be assumed, and only masses and motions

be regarded as realities."

He enlarged still further on the subject of fields, and

while he was describing the technical details, I saw him

metaphorically enveloped in a magnetic field of force. Here,

too, an influence, transmitted through space from point to

point, made itself felt, and there could be no question of

action "at a distance" inasmuch as the effective source was

so near at hand. His gaze, as if drawn magnetically, passed

along the wall of the room and fixed affectionately on Maxwell

and Faraday.

VALHALLA

Interior of the Regensburg Walhalla. [Photo by

Christian Horvat]

Galileo's Tomb. Photo by Ricardo André Frantz.

Painting by Rita Greer.

Figure from Newton's Principia,

I.ii: "The areas, which revolving bodies describe

by radii drawn to an imovable centre of force ... are proportional

to the times in which they are described."

Bullet in flight. Photo by Ernst Mach, 1888.

Chart by Cutler.

Humboldt und Bonpland in der Urwaldhütte

by Edouard Ender, ca. 1850. [Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der

Wissenschaften]

Added to these there are a great number of inventions,

in particular those connected with problems of aviation, such

as the parachute (before Lenormand), and so forth.

Schadow's bust of Copernicus in the Regensburg Walhalla. [Photo by

"Matthead"]

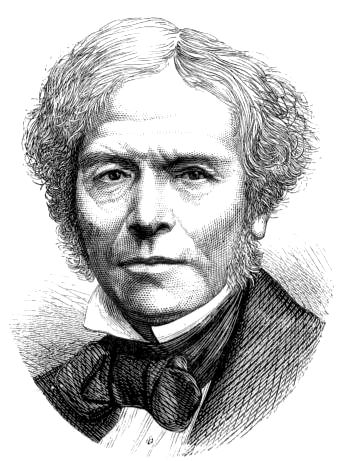

Eugen Dühring

The Regensburg Valhalla. [Photo by

Michael J. Zirbes]

Alexander Stoddart's new (2008) statue of

Maxwell on George Street in Edinburgh. [Photo

by

Kim Traynor]

CONTENTS: