Kayaks Go High-Tech, Testing Marine Robotics

by Kathryn M. O'Neill, MIT News OfficeMIT researchers are working toward the day when a team of robots could be put into action like a team of Navy SEALs - doing such dangerous work as searching for survivors after devastating hurricanes or sweeping harbors for mines.

Working in labs that resemble machine shops, these engineers are taking small steps toward the holy grail of robotics - cooperative autonomy - making machines work together seamlessly to complete tasks with minimal human direction.

Joe Curcio, left, helps launch a SCOUT for experiments off the coast of Pianosa, Italy.

The tool they're using is the simple kayak.

The researchers are taking off-the-shelf, $500 plastic kayaks and fitting them with onboard computers, radio control, propulsion, steering, communications and more to create Surface Crafts for Oceanographic and Undersea Testing (SCOUTs). The research is funded by MIT Sea Grant and the Office of Naval Research, with hardware for acoustic communications provided by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Much of the technology being tested is ultimately intended for use in underwater robots, or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), but testing software on AUVs can easily become a multimillion-dollar experiment.

"I want to have master's students and Ph.D. students that can come in, test algorithms and develop them on a shoestring budget," says John Leonard, associate professor in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering. Leonard, together with Joseph Curcio, a research engineer in Mechanical Engineering, and intern Andrew Patrikalakis unveiled SCOUT last fall in a paper for the IEEE Oceans Conference.

SCOUT is an inexpensive platform that eliminates the need for communication underwater - one of the more difficult problems posed by AUVs. "One of the biggest challenges underwater is that we can't transmit electromagnetic radiation a long distance," says Leonard.

Joe Curcio readies SCOUTS at the Keyport Naval Base, near Seattle.

Operating on the surface means that SCOUTs can take advantage of such technology as wireless Internet and global positioning systems (GPS), which don't work underwater. Researchers are thus free to focus on fine-tuning other necessary robot functions, such as navigation - all with the goal of creating a system that works so seamlessly that a lot of communication isn't necessary.

"In order to be effective with robots in the water, you'd best not have a plan that relies on a lot of communication," Curcio notes. "To be effective with a fleet of vehicles and have them do something intelligent, what you really need to do is have the software be so robust that communication between the vehicles can be kept to a minimum."

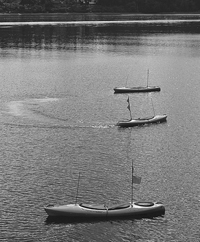

Three SCOUTs in the waters off Pianosa.

Curcio, Leonard and Patrikalakis have built 10 SCOUTs so far, four of which are owned by the Naval Underwater Warfare Center and in the care of Michael Benjamin, a visiting scientist in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering. Currently, the SCOUTs are being used in a variety of collaborative efforts at MIT. As Leonard and Curcio explain, SCOUT was designed to be a platform upon which others can build.

"The analogy was born that we should build it like the pickup truck. All we have to do is make it so that it drives with a known set of controls, or interfaces, and has a payload capability," says Curcio. "And the users, once they learn how to operate it - like a driver gets in and out of a car - should be able to easily get on board with another one, even though the payload may change."

Software developed on SCOUT may someday help AUVs search the sea bottom for plane wreckage or allow kayaks to find shipwreck survivors. And, adds Leonard, "We keep thinking of new applications."