Fall

2001

![]()

Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan adds psychological quirks and foibles to rational economic models

Spotlight on the Center for International Studies

World theater takes center stage at the MIT Theater Arts Program

Kudos to exemplary SHASS staff

The Shakespeare Project leads the humanities into the digital universe

![]()

![]()

Soundings is published by the Dean's Office of the

School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT

Comments and questions to shass-www@mit.edu

Biting the hand that feeds it

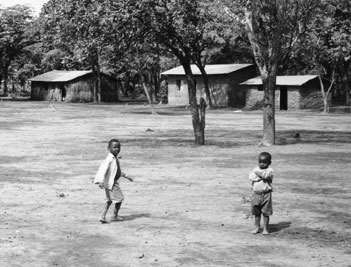

Children in the Lugufu refugee camp in Tanzania, where refugees fled following the 1998 civil war in Congo.

Photo: Sarah Lischer.

Center for International Studies

When people are the focus of aggressive genetic research, who owns the information once it is decoded? What happens to the decoded biodata? Is it sold to the highest bidder in the pharmaceutical marketplace? Used in scientific research? And the community—Micronesians, for example, whose gene pool has been heavily explored by genetic researchers—how do they profit from the excavated information?

The issues and ethical minefields connected to biotechnology—and by extension, science and technology in general—take the spotlight in the Program in Human Rights & Justice (PHRJ), the latest initiative of the Center for International Studies (CIS). International in scope, the PHRJ agenda focuses on the impact of science and technology and the emerging global economy, two arenas in which MIT has a comparative advantage. "These are precisely the areas in which the mainstream human rights discourse is seriously wanting," says Professor Balakrishnan Rajagopal, director of the PHRJ, which is co-sponsored by the Department of Urban Studies and Planning. "That a place like MIT, the first science and technology school to establish a human rights center, is taking the lead in influencing the debate marks a significant change in the way science and technology schools function," he says, adding that the Program's approach will be highly interdisciplinary. The Program's advisory board includes Nobel laureate Amartya Sen and Noam Chomsky and judges from the Supreme Courts of Canada, Australia, and India. In collaboration with seven other human rights centers, the Program also has launched an internet New York Review of Books-type quarterly to help people keep up with the field's mushrooming literature.

"The Program is the single largest investment ever made by the Center, and a way to balance the activities in which CIS is distinguished," says CIS Director Professor Richard Samuels. The Program joins the three flagship efforts of the Center, now celebrating its 50th anniversary: the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI), the Security Studies Program (SSP), and Seminar XXI.

MISTI, the first and largest program of its type in the country, features "regional studies for the real world," says Samuels. "We're not training people to read Buddhist scripts or German philosophy, although we hope they'll do that too. We're providing skills they'll need as scientists and managers in research settings in foreign countries." What began in 1981 as applied studies in Japan has morphed into additional programs in China, France, Germany, India, and Italy, which collectively have trained 1200 students.

The CIS Security Studies Program, a rare mix of technical and policy expertise, is a graduate-level enterprise specializing in war and peace. Considered one of the nation's strongest security studies programs, it emphasizes strategy, technology, arms control, and political and bureaucratic issues.

Using a "Rashomon-light curriculum," the nationally unique Seminar XXI takes mid-career foreign policy and security professionals and broadens their perspectives, says Samuels. "We teach them paradigms—liberal, Marxist, conservative—and how to think in alternatives. The graduates have risen to great heights in their professions and are an interesting bunch."

Also unique to the CIS firmament are the Crisis Simulation Initiatives, which examine U.S.-Japan relationships and security in Asia's explosive landscape. By imagining and role playing the region's political and economic dynamics over a 12-year time frame, academics, industry professionals, and press model strategic planning scenarios. The games, run jointly with the Political Science Department, have won kudos internationally for their educational value. CIS also is establishing, in collaboration with the MIT Technology and Policy Program, the Policy Center for Emerging Technologies. Now in the planning stage, the Institute will specialize in forecasting and management and focus on three technologies—genetic engineering, micro- and nano-technologies, and ubiquitous computing.

What characterizes CIS programs, says Samuels, is "the willingness to speak truth to power." A classic case in point is Theodore Postol's whistle-blowing work, which revealed that the Patriot missiles produced by a major MIT supporter didn't perform as advertised during the Gulf War. Highlighting the CIS proclivity to study the gulf between rhetoric and reality, but uncomfortable about how self-serving it might sound, Samuels notes the joke travelling the CIS halls: "We really are willing to bite the hand that feeds us."

For more information on CIS, visits its website: http://web.mit.edu/CIS/www/index.htm

![]()

Copyright © 2001 Massachusetts Institute of Technology