Fall 2001

Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan adds psychological quirks and foibles to rational economic models

Spotlight on the Center for International Studies

World theater takes center stage at the MIT Theater Arts Program

Kudos to exemplary SHASS staff

The Shakespeare Project leads the humanities into the digital universe

![]()

![]()

Soundings is published by the Dean's Office of the

School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT

Editor:

Orna Feldman

Editorial Assistance:

Sue

Mannett

Elisabeth Stark

Layout and Art Direction:

Conquest

Design

Design:

MIT

Publishing Services Bureau

Online Publishing:

Feisty Design

“There's something quite wrong with the standard economic model. We need to add some factor, though what we need to add is unclear.”

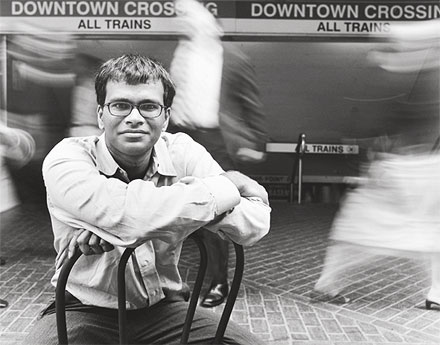

Economist Sendhil Mullainathan, adding irrationality to an empirical universe.

Photo: Graham G. Ramsay.

Getting a fix on complexity

Sendhil Mullainathan is the Mark Hyman, Jr. Career Development Assistant Professor of Economics. A Sloan Foundation Fellow, as well as the first recipient of the Zvi Griliches National Fellowship at the National Bureau of Economic Research, he received the 2000 Graduate Student Award for Outstanding Faculty Member from the Economics Department. Twenty-eight years old, he is an emerging leader in behavioral economics, one of the hottest trends in economics. His fields of interest include development, economics and psychology, and labor economics.

Let's start with a brief explanation of behavioral economics and how it differs from mainstream economics.

Mainstream economics begins with fairly simple but powerful assumptions of human behavior, which are that people are self-interested, completely knowledgeable of their own preferences and able to maximize them consistently, and completely able to make inferences about the world around them. There's uncertainty, but the rules of probability will tell us how to deal with them. That's what drives a lot of economic models. Behavioral economics, by contrast, changes the assumption of self interested maximizing individuals. It tries to open things up. Think of people having self control problems. Let's say you find yourself eating more dessert than you wanted to. The rational model holds that its inconsistent to say, 'If the dessert is there I'll eat it, but I'd like to not have the dessert there.' Either you like the dessert or you don't like the dessert, and that's it.

How does behavioral economics respond to this dilemma?

We're trying to incorporate psychology into the economic models. To be honest, a lot of what we try to incorporate seems so obvious that people's response at some level is, 'Why weren't we doing this all along?' Consider savings and self control. It's surprising that economists have been doing savings for 50 years without incorporating the phenomenon of self control seriously. But you can look at it two ways. One is that we ignored these elements precisely because they weren't so important. The other is that we were missing the obvious all along, maybe because we only talk to each other.

A problem of academics having blinkered views?

Exactly. That's probably one of the core questions in all of social science. If you talk to psychologists, they have the very same blinkers on, just for different things. Psychologists rarely think about trying to translate their experimental work into empirical work on, say, welfare. As economists we have our own blinkers, which are rational models that we've been using for the last 50 years. What I'm struggling with now is whether it's a good thing to have blinkers and walk down a specific path, with all the added benefits of specialization. Or is it time to integrate? And was specialization a good idea at all? Should we have taken a more comprehensive approach from the beginning?

Regarding the 'either you want dessert or you don't want dessert' example—it patently does not represent how people think.

Right. In my mind the biggest moves forward for behavioral economics are going to come because we've seen empirical evidence that says, this is just not a good enough model. So, self control may be a problem in savings but does it really matter? What we've seen is, in fact, that self control is a factor, an abstraction, that we ought not get rid of. Let me give you an example of empirical evidence that really changed the way people think about the savings thing. One study looked at a firm and their 401(k) setup. For several years, the firm had a plan that if you didn't do anything, you didn't participate in the 401(k). Then they changed this to a plan where the default—if you didn't do anything—was that you participated in the 401(k) at a rate of 2%. And all you have to do to not participate is check a different box. From the consistent maximizing model, this should have no effect. There's no cost to checking a box. But the change has tremendous, long lasting effects in people's participation in the 401(k). When participation is the default, 40% more people participate.

What does that say from a behavioral economics point of view?

These are large effects, where the standard model says there should be none. There's something quite wrong with the standard model. It fails to deliver in a context important to economists—savings. We need to add some factor to the model, though what we need to add is unclear.

How would you articulate what it is you have to add in?

One way we could explain this is to say that people are infinitely procrastinating. They say, 'I've been meaning to figure out my 401(k) for a while and whether I should be at 2% or 4%.' Next week something comes up and they put off the decision. So, small costs lead to infinite delay. If the default is 2%, you're contributing while you're delaying. Another possibility is that a lot of people just don't know how to conceptualize this thing. 'What should I do? Should I save anything? How much should I save? I have no idea.' It leads to paralysis. It's not even about procrastination, it's legitimization of the position the firm chose as the default. So we could write down several hypotheses, which are all outside the normal frame of mainstream thinking about this problem.

You would add some psychological variables to the equation?

Yes, but that's what frightens most standard economists. In this discussion I've raised two variables and I could probably raise five more. It's like opening a Pandora's box, because as we add more variables the model becomes useless. It doesn't do what a good model is supposed to do, which is abstract from the details and focus on the key issues. The tension is—have we abstracted to the right level? This is a microcosm of social science: more complicated models may be more right in one sense, but you start to lose the usefulness of the model as you start to pile on things.

Is there any possibility that mathematical modeling and algebraic calculations can encompass the complexity of psychology?

If you want an accurate model of how people think, it's almost certainly the case that simple math isn't going to be able to do it. But if the goal is to get an approximate model that's useful in applying in a few situations—that's a different story. Let's say you're hiring job candidates and you want to get information from their résumés and interviews and you want to understand how people translate that into a decision. If you want to understand that decision in thorough detail for one person—any mathematical model is going to miss a lot. But suppose I want to understand that for employment movements in the economy as a whole and whether certain racial groups find it difficult to be employed. Then we might be able to get much more mileage out of a simple model. Have we missed 50% of what's going on? Yes, but we captured 50%. The difficult thing about social science is that you know you're never going to be right, you're always going to be just approximately correct. Are we ever going to completely understand the economy? Almost certainly not. But are we going to be able to make better decisions about it? Yes. It's refining our view of how we think about things.

What kind of reception do behavioral economists get?

For a long time the reception was cool and defensive. Now, the reception is, if anything, too good. You know, our old logic for why we wanted to stick to the basic model was very sound. Sometimes I find myself more in the rational camp, saying, 'But so what? Why are we thinking about this? Where is the evidence this is important?'

What originally drove you to economics?

I started off doing math and theoretical computer science. Somehow it just seemed like economics was more useful. When we look at the problems around us of poverty and unemployment, a lot of the hardships people face, they're economic in nature. It seems we've had a lot of technological change but that change hasn't really reduced the misery that's out there. If I had been involved in designing a social program, or if we understood better why developing countries have such a hard time developing, the gain might be much higher. Maybe re-thinking these big social problems in a structured way can contribute to that.

Did living in rural India until age seven play a role in your thinking?

Definitely. You see a lot of poverty in the streets and that's striking. But you also see that they earn some order of magnitude less than we earn, yet the happiness they have is not so obviously lower. It forces you to think there's a lot more to what goes on than the simple way we look at it. Those are the things that drew me to behavioral economics, which is that in a simple materialistic model I should be tremendously happy relative to them. But there are things I don't have—like a closely knit extended family life. Or another example—loneliness. It's rare that it plays a role in our economic models. Yet if I think of the biggest determinant of happiness here, versus in India, I'd say there are a lot of lonely people here and not so many in India. I think loneliness is something we shouldn't have abstracted away.

How do you factor loneliness into an economic framework?

What's tough to work on are data. Let's suppose I'm actually a lonely person, but when you ask me how lonely am I, I don't answer how lonely I am in an absolute sense but how lonely I am that day relative to my usual level. To move forward on loneliness we need to work on how to measure it. Let's think about whether people take loneliness into account when making decisions, like moving to a nursing home. In the past we might have said, giving pensions to the elderly is a good thing because then they can be self sufficient. But one side-effect might be that the family feels freer moving away because they don't need to take care of the elder. If we had a good measure of loneliness, that would enter into our discussion. Once we start being able to measure these things precisely, or even sort of, it will pervade discussions.

You've also done some research on stereotyping.

Yes, and that's what got me interested in Allen Iverson (of the Philadelphia 76ers). He's extremely interesting because he's got all the elements of a stereotype that make people not like him—he wears corn rows, he has inner city body language, he has tattoos. And his attitude—he'd miss practice and look like he wasn't taking anything seriously. Then this year he turned himself completely around and worked really hard. But now there's a dissonance, because he's really hard-working, but he still has the corn rows, the tattoos, the language. Some people are still responding with skepticism.

So how does this play into your work?

On two fronts. A key element of bias is compressing the entire category into a core stereotype. Iverson suffers from the categorization: "Oh, I know this kind of guy, it's the ghetto black male." The other way he gets miscategorized is on the basketball court—he suffers from how a great basketball player is defined, which uses Michael Jordan as the measure. Jordan could do a lot of stuff in the air. He had fancy dunks and great footwork. Those elements were the lens through which we were looking to define great basketball players. You look at Alan Iverson and the way he shoots the ball looks nothing like Jordan. His greatness is altogether different. It's a little like art. If you're only used to seeing the great Realists, those are the elements you look for. Then the Impressionists came along and forced you to look at everything differently. And that's what I like about Iverson—he's getting you to see things that you never would have been able to see.

How does that fit into economic decision-making?

In the economic framework, you overly compress everything that's in the category and consider the implications for economic decision-making. Today, people want to know whether we're in a recession. We weren't talking about recession a year ago. We switched from the category of 'boom' into the category 'recession.' When we thought it was a boom we over-stereotyped it. Now that we think it's a recession we're over-stereotyping it. What we ought to have said was, sort of a boom, sort of a recession. That unwillingness to back off and say 'Look, I'm not going to categorize this' may actually be part of the problem in our fast move towards a recession. Stereotyping is a pervasive phenomenon and has implications—for discrimination, for how people think about the aggregate economy, how people think about individual firms, how we think about all sorts of things. It may be the simplest way to think about the world, but once you recognize that that's what you're doing, you can force yourself to attend to it.

You have been quoted as saying that behavioral economics may be a fad.

If you want to be cynical, it has all the elements of a fad, which is that people were very against it until 10 years ago. Then some well-known people started to do it and it started to take off. But there are elements that have the feel of being here to stay, like people doing solid empirical work. It's hard to tell which way it's going to go. Maybe 10 years from now we'll look back and say, 'Wow, did people get carried away. There are a lot of useless models taking up lots of journal space.' Or maybe we'll look back and say, 'Oh, those were the glory days when all the foundations were laid and the field matured.'

![]()

Copyright © 2001 Massachusetts Institute of Technology