|

|

||||||||||||||||

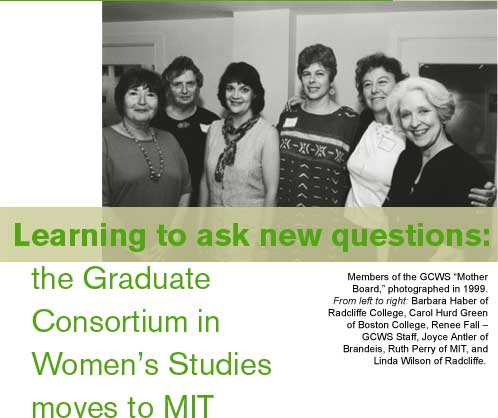

The phrase "learning community" is a popular buzzword in recent literature on educational reform...but what exactly does this mean? What would a community built around "learning for the sake of learning" look like? And how would such a community function? One answer may be found in the Graduate Consortium in Women's Studies (GCWS), which is today located in the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT. GCWS is a collaborative, interdisciplinary institution made up of women's studies scholars from eight Boston-area universities. The Consortium was designed in the late 1980s with purely pedagogical goals, by feminist academics who were invested in training the next generation of feminist scholars, and who believed in the potential of collective learning and in the strength and sustenance created by an academic community. The Consortium began (appropriately enough, given its collaborative nature) as a conversation among friends around a kitchen table. That kitchen table belonged to MIT Professor Ruth Perry, one of a group of founding members of the Consortium (called, tongue in cheek, the "Mother Board"), and an ongoing advisor to the program. According to Perry, the initial goals of the Consortium — which remain unchanged today — were to advance knowledge about gender, and to train the next generation of feminist scholars by stimulating a crosspollination of ideas between institutions, disciplines, and individuals. "The success of feminist scholarship," Perry explains, "has sometimes meant that people are increasingly located in their own disciplines, in their own departments. They no longer need to reach out to one another for support and corroboration. So we wanted to create an institutional frame to retain that interdisciplinary focus, which inspires so much of the scholarship involving gender." Today, though women's studies programs within each of the member institutions are generally much stronger than they were 15 years ago, this cross-pollination is no less vital — and no less exciting. "Teaching in the Consortium," Perry explains, "really allows you to break new ground, and teach where your own research interests lie. It's intellectually incredibly challenging, because every course is taught with at least one other scholar from another discipline, and another institution. And you're teaching students who may come from still more disciplines. This creates an interdisciplinary meta-conversation about meaning — you're always translating between disciplines, and having to explain what matters from the context of your own discipline, and understand what matters from the context of another discipline." The Consortium — which found its first home at Radcliffe College, and remained in residence there from 1993 to 2005 — is governed by a board made up of representatives from each of the member institutions, which now include Boston College, Brandeis University, Harvard University, MIT, Northeastern University, Simmons College, Tufts University, and the University of Massachusetts, Boston. The Consortium offers two or three graduate-level courses each semester, each of which represent collaborations between faculty members from different disciplines, and from at least two different member institutions. Member institutions pay dues each year to cover operating costs, and also agree to count Consortium classes as part of their faculty's course load. No course is taught more than a few times, and each proposed course outline is carefully scrutinized by Board members, who offer detailed suggestions and criticisms to ensure that the course is both truly interdisciplinary and relevant. This means that each course calls for a substantial time commitment on the part of faculty — which can sometimes be daunting for junior faculty, who often are under intense pressure to complete and publish their research. One young scholar who found a way to participate in the Consortium despite this pressure was history professor Anne McCants, who arrived at MIT in 1991, just as the Consortium was gathering momentum. McCants, whose background is in early modern Dutch history, got a call out of the blue one day from an art historian at neighboring Tufts University, who was interested in team-teaching a course. Though McCants was a little concerned about the time commitment, she was also intrigued, and agreed to her colleague's proposal. The course, which they called Boundaries of Domesticity in Early Modern Europe, paid off; McCants calls the experience one of the best things she did as a junior faculty member. "It was such an intellectually rich experience," McCants explains. "It got me connected with people outside my discipline, my university, and there was a real agenda from the Consortium board — and real oversight — to make sure that the course had breadth, and depth, and that we covered lots of methodological ground." It was a bit intimidating at first to be teaching with two senior professors. (McCants recalls that she felt a lot of pressure to "do her homework.") But the experience turned out to be incredibly rewarding, and actually helped her develop her own background in feminist scholarship. Though she had long been conducting research that had a significant gender component, McCants had little formal training in women's studies, and the Consortium has allowed her to broaden that aspect of her own scholarship.

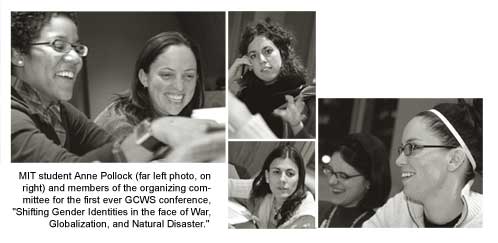

Other MIT faculty members who have taught in the Consortium concur regarding the benefits of the experience. "The rewards for me have been spectacular," says Ruth Perry. "I've written a lot out of the energy and insights that have come from the work I've done in Consortium classes." One example of this productivity is Perry's recent book Novel Relations, The Transformation of Kinship in English Literature and Culture, 1748–1818, a study of the transformation of family in English literature as a function of social changes. Perry notes in her acknowledgements that many of the ideas in the book were hatched in Narratives of Kinship, a Consortium class that she taught jointly with Christina Gilmartin, an anthropologist from Northeastern University (now teaching at University of California, Riverside). "Narratives of Kinship was just a wonderful class, and we put together a great syllabus," Perry explains. "We would ask questions like, 'How is Clarissa an ethnography? How are anthropological accounts fictional?' It was really interesting — and I was so fascinated by Christine's perspective." With a chuckle, Perry adds, "I loved having my very own anthropologist!" MIT faculty members have always been deeply involved in the Consortium, so when the institution outgrew its first home at Radcliffe at the end of 2004, MIT seemed to many to be its next logical home. Anne McCants, who was co-chair of the board when the need for a move became clear, notes that she and other MIT faculty on the board did a great deal of legwork to prepare the move. "We visited each of the school's deans," McCants explains, "as well as Ike Colbert in the Office for Graduate Students, because that seemed like a logical place to generate support, and then we presented our case to the Deans' Council Group chaired by the Provost, so we did a year and a half of work to build support across all of MIT's schools. And we received an immense amount of support." It was a relatively easy pitch, McCants notes, in part because of the inexpensiveness and the clear benefits of the program. "In the grand scheme of what it costs to run a university like MIT, this is a bargain. We run our whole budget on less than a senior faculty salary! And the school gets impressive course offerings, an increased focus on gender...and credit for the work of a whole group of very good people." While the Consortium is good for MIT, the benefits are not all one-sided. "The humanities professors at MIT are especially glad to have the Consortium here," Perry points out, "because many of us do not have graduate students of our own. So it's a great pleasure to teach these courses. In addition, MIT is a logical home because it has always been hospitable to energetic new enterprises — and it has always been interested in interdisciplinary work. So the interests line up quite well." STS graduate student Anne Pollock, who's writing her dissertation on how race, sex, and sexuality get articulated through the history of arguments about cardiovascular disease, concurs with this assessment. "One of the good things about MIT is that it is historically open to the broader community, and this makes it a logical home for the Consortium." Pollock, who took a Consortium class on Transformations of Families in her first year of studies at MIT (McCants was one of the team of professors for the course), participated this spring as a member of the organizing committee for the first ever GCWS conference, "Shifting Gender Identities in the Face of War, Globalization, and Natural Disaster." The conference, which took place March 30–31 at MIT, allowed graduate students and faculty from member institutions to present and discuss cutting-edge student work, and to share skills and resources. Pollock — and the Consortium members — hope the conference will be the first of many. When asked if the Consortium made a difference in her own education, Pollock's response makes it clear that the Consortium's goals are bearing fruit in the next generation of scholars. "You know," she muses, "without the Consortium, you could wander around this city in the center of all these folks who are tackling questions similar to the ones you're posing, and you might have no idea that they're there. The Consortium puts you in touch with people who are thinking about similar questions...and more important, it lets you see how folks with similar interests are asking questions differently from the way that you are, based on their own academic background." Today, at MIT, students and faculty in the Consortium are learning from the questions posed by their peers all over the Boston area — all thanks to those early conversations around Ruth Perry's kitchen table. For more information about the GCWS, contact Andrea Sutton, GCWS Program Coordinator, at 617-324-2085 or visit the GCWS Web Site: http://web.mit.edu/gcws |

|

|||||||||||||||