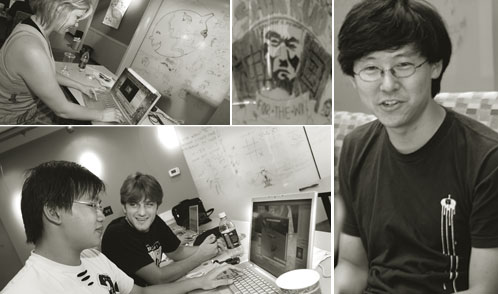

Most of the students wandering the halls of the new GAMBIT game lab in late July seem to share a common expression: two parts concentration, one part excitement, and one part glee.

The concentration results, most likely, from the technical, aesthetic, and design challenges they face as they fine-tune the games that they've been developing all summer. And why the excitement and glee? Well, first, they feel fortunate to be part of a pilot group of gaming pioneers. Second, they get to work on games (and get paid for it) all summer long. And finally, they get to work on a team with highly talented peers in a new research lab in the heart of Cambridge's Kendall Square.

The lab consists of seven large team rooms, located along a circular maze of corridors, and separated by glass memo walls. These have been liberally sprinkled with prototype sketches, to-do lists, and mock-serious challenges from one team to another. ("I will eat your souls!" proclaims one such note.) Another comprises a list of essential game features, including hero progression, monster variation, environment, and weapons.

Each of the large rooms is occupied by a team of about seven young people—a mix of MIT computer science and comparative media studies students, along with students from various universities in Singapore. (The exception is the audio group, which comprises only two students; rather than working on a complete game, they provide sound services to each of the six game teams.) Many of the teams have bulletin boards covered with Post-it notes in three different rows: to do, in progress, and completed. The notes show the team's progress as they complete each two-week "sprint," and prepare for presentations of their work at the end of this period.

GAMBIT itself isn't much older than the space it occupies. The project, which formally got off the ground in the spring of 2007, is a joint venture between MIT's comparative media studies (CMS) and computer science programs and the Singaporean government. The project is directed by Philip Tan, a 2001 MIT graduate who completed a master's degree in comparative media studies in 2003, and then worked for several years as research manager with The Education Arcade, an MIT initiative that focuses primarily on education-related games. In 2005, Tan returned to Singapore to work with the Media Development Authority in the video games industry department.

At around the same time, the Singaporean government decided to invest in digital media research on a large scale. Government officials contacted CMS, and solicited proposals for ways to collaborate with the Institute. One of these proposals, generated by CMS professors Henry Jenkins and William Uricchio, looked exciting to Singaporean officials, and the government steered it towards Philip Tan. It was a serendipitous connection: Tan was thrilled to be working with his CMS mentors again, and the three refined and expanded the proposal, eventually arriving at a blueprint for GAMBIT.

GAMBIT is a natural fit for CMS, an interdisciplinary program committed to thinking across media forms, theoretical domains, cultural contexts, and historical periods. CMS has long been involved in the study of games; Jenkins, for example, has been studying games for more than 16 years, and the program has been actively focusing on the medium, and its interaction with other media, for nearly as long. In 1997, the program co-sponsored From Barbie to Mortal Kombat, a conference on gender and computer games, with the Program on Women's Studies, the Media Lab, and the Program in Science, Technology, and Society. In 2000, CMS hosted another national conference on games, Computer and Video Games Come of Age, looking at the emerging gaming entertain≠ment market. And in 2003, CMS established the Education Arcade—an initiative that studies the social, cultural and educational potential of educational gamesówith the University of Wisconsin's School of Education.

In recent years, according to Jenkins, games have been emerging as artifacts of national culture, much in the way that art cinema has long reflected national culture. As such, games become an important window on social, cultural, and technological trends around the world. Because of this, interest in the study of games is growing rapidly among students in CMS, many of whom are migrating away from film in favor of games. "It's not that students aren't interested in film today," explains Jenkins, now a lead investigator at GAMBIT, "but when I first got here sixteen years ago, my students overwhelmingly wanted to become David Lynch, and Quentin Tarantino. Now they want to be Will Wright, and Shigeru Miyamoto. They want to be game designers."

The creation of GAMBIT has given CMS a center around which games instruction can take place. "We're already discussing adding more courses to the curriculum," Jenkins explains, "that will allow us to build on the GAMBIT experience, and provide more opportunities for our students." In addition, the lab is benefiting the rapidly increasing number of MIT students who choose to double major in CMS and computer science. "GAMBIT has also allowed us to build a stronger connection between CMS and the computer science department," Jenkins says, "creating a shared research space where those students who are double majors can work on projects that meaningfully prepare them for their careers. This project allows us to take a student from conceptualization all the way through user testing on the development of a game—in other words, a set of experiences that are crucial for students who want to be employed in the game industry."

GAMBIT is also a natural fit for the needs of the global game industry. The goals in this realm, according to Jenkins, are twofold: first, to create space for innovation and research in the games industry; and second, to foster a global engagement around the development of games as a cultural force. "The games industry," Jenkins explains, "has gone through a rapid cycle, moving from an entrepreneurial economy to a studio-based mode of production. So, like Hollywood, the industry is concentrating on a smaller and smaller number of big companies that are very risk-averse. This creates high technical standards, but it also doesn't allow much room for individual innovation and creativity. There's little interest in exploring games that won't sell immediately. So in effect, the core market gets served very well, but other potential markets are underserved."

As for the challenge of fostering global engagement, Jenkins believes that Singapore is an ideal partner. "Singapore looks to be a really interesting country to collaborate with," he points out, "first because it's in Asia. Three of the four most powerful games-producing countries in the world are in Asia: China, Japan, and Korea. And while Singapore isn't there yet, they already have a strong digital economy, and a reputation for technological innovation. Also, they form a gateway between East and West, which means that it's a kind of multicultural society."

The relationship, according to Tan, has already been extremely beneficial to both parties. "This project will allow Singapore to get some insight on more global industry-wide issues that it could maybe take some leadership in," Tan explains. "And for CMS, a game research lab has been a fantasy for a while, so it works very, very well. The international element was particularly attractive to CMS, as well, because the program has always had an international focus."

Structurally, GAMBIT consists of several interrelated elements. The summer program, the most visible face of GAMBIT, brings together students from MIT and Singapore to design games that respond to a variety of research challenges. The students are grouped into teams based on their skill sets. Typically, the Singaporean students arrive with strong skills in design, art, programming, or sound engineering, and are paired with MIT students who have been trained to think about game design processes and principles, and who also are immersed in games research. The goal of the student designers is to build a game that puts some of that research into practice, quickly moving GAMBIT from the realm of the theoretical to the applied.

The research itself is another facet of GAMBIT, and is conducted throughout the year at MIT (both in the computer science department and at CMS) and in Singapore. Research projects are selected by GAMBIT's lead investigators, and are designed to explore games as a medium. The projects cover a broad range of topics, including technical, economic, cultural, and aesthetic questions.

"We're challenging the students," Jenkins explains, "to really think about expanding games as a mode of expression. We're lucky enough to be free from all the usual constraints: market constraints, platform constraints, genre constraints. We want GAMBIT to enable the teams to explore new technological developments, new cultural opportunities, and new underserved groups. We really seek to advance games as a medium."

This summer, GAMBIT hosted 32 students from Singapore, along with 13 MIT students. One of the six teams was led by Eitan Glinert, a Master's student in computer science who also received his undergraduate degree from MIT, and then moved to Washington D.C., where he worked with the Federation of American Scientists on an educational game called Immune Attack. Glinert's group became interested in the question of whether they could design a game that was equally accessible (and com≠pelling) to both sighted and visually impaired users. "My original thesis question," Glinert explains, "was, can we make a video game that is accessible to the visually impaired? Pretty quickly, we started refining that question, because there already are games out there that are accessible to people who are visually impaired. But what about a game that's equally accessible to visually impaired people and sighted people?"

A secondary research question involved the Wii controller, a motion-sensing game controller that emerged onto the game scene in the past year. "The Wii is wildly popular," Glinert explains. "And, it's 100 percent inaccessible to blind people. They can't see what's on the screen, which means that there's this new fun toy out there that they can't use. So what if we use the Wii as an expressive control interface for our game, so that visually impaired users can experience the Wii in a meaningful way? That's another one of our research goals."

The game Glinert and his team have come up with (without giving away too many proprietary secrets) involves using the Wii to respond to, and predict, sounds, as players build up a multilayered pop instrumental song. During soundings' visit to the lab in July, lead tester Mark Sullivan, a sophomore computer science major on Glinert's team, is trouble-shooting some minor glitches in the game. For example, the Wii controller is su≠posed to vibrate when players correctly hit a beat, but at the moment, this feature isn't working. When Sullivan finds a glitch like this, he identifies which teammate is responsible for the feature, and lets them know that something isn't working. "I also have to make sure it's documented," Sullivan explains, "so I use an online bug-tracking system called Mantis. I classify things by severity, describe what the bug is, how to reproduce it, and assign it to whoever's responsible." Sullivan is participating in GAMBIT through a UROP assignment, which means he gets paid for his time. A lifelong gamer (he became hooked in kindergarten when he received his first Nintendo set), Sullivan is enjoying his summer, and—depending on his schedule—is hoping to extend his engagement into the fall.

Because the lab is so young, it has yet to be determined whether GAMBIT will be able to deliver on its goals of producing six to ten innovative new games each summer. (So far, the preliminary results look extremely promising.) Also unclear is exactly what happens when the lab does come up with a viable product. The games industry is highly lucrative, and the potential profits could be significant. Whatever the profits, however, Jenkins hopes that GAMBIT will have an early and significant impact on the industry. "What we're trying to do," Jenkins explains, "is to translate games research into a playable demo that can speak to the industry in a meaningful way. Our success rests in part on whether we're able to do that."

In addition, Jenkins hopes that GAMBIT will have more intangible types of impact. "I think some of the impact GAMBIT can have is sparking the public imagination about what games can do," he muses. "This is still an emerging medium, and the industry has set constraints on what kinds of games can be produced. We hope that the prototypes we develop will expand the vocabulary of games and thus help to inform future developments inside the industry and beyond. We also hope that our students will have an impact. If we place these people in the games industries around the world, they will be in a position to make a difference."

Yes, GAMBIT is fun and games—literally. But as Jenkins makes clear, this is also a serious, and culturally significant, endeavor.