Source: The Cambridge Book - 1996 (Engraving courtesy Harvard University archives)

|

|

|

|

Urban Slivers: |

||||

|

|

An

Investigation of the Bow Street / Arrow Street Area - Cambridge,

MA

|

||||

|

|

Source: The Cambridge

Book

- 1996 (Engraving courtesy Harvard University archives)

Storyboard

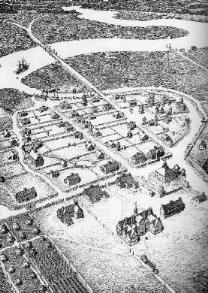

The overall story of the Bow Street neighborhood dates back almost to the founding of Cambridge in the 1630s. Whereas the parts of Boston that date from this time have mostly developed into the scale of a large city, this part of Cambridge has retained a more village-like character and scale after nearly four centuries. This idyllic and perhaps idealized perspective of early Cambridge looking south from Harvard shows the dominance of the natural landscape during the first few centuries of the city's existence. The creek (now buried) that defines Elliot Street and the western boundary of Harvard Square has a great visual presence in this dramatic engraving, leading the eye to the snakelike meander of the Charles River. The document's visual richness is both compositional and technical; the hatched lines define a great variety of textures that emphasize the total landscape rather than just the built environment.

In this seventeenth century view that just barely makes it onto the western terminus of the Bow Street neighborhood, the notion of boundary is already in question. Like many more recent maps, the point at which to crop the image or map is frequently an interruption in the Bow Street area, which is currently distinct and separate from the Harvard-Holyoke area to its immediate West. In historical perspective, however, this was not the case, as Bow Street in particular was a visually included part of the village-like area south of Harvard University.

Much as birds-eye views are visually evocative, it is rare to have a large quantity of aerial perspectives with a correspondence useful for analysis. Therefore, I will use plan-view maps to trace the site through history. Even for an area with as rich a history as this neighborhood, the historical documents only give discrete views in sequence, a storyboard rather than a film. Nevertheless, the interaction between private development in Cambridge and the institutional life of Harvard is evident in these snapshots of the site's evolution to its current state.

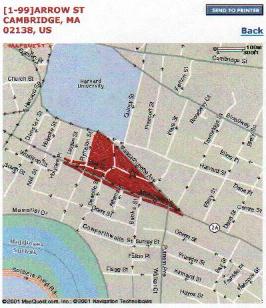

As a reminder from Part 1, here are the boundaries of the site from a contemporary Mapquest search:

(c) 2001 Mapquest.com, inc.

Snapshots (Click on images for larger versions)

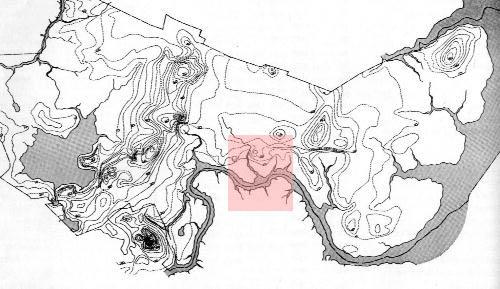

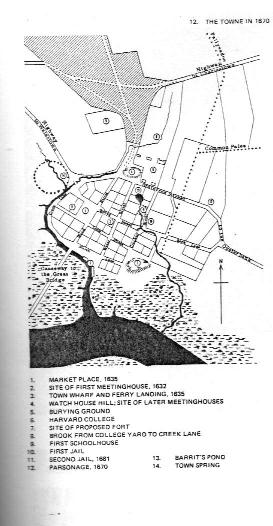

Source:

Emmet,

1978 (illustration of 1600 Map)

Cambridge's history as a village is intimately linked to the natural topography and the later man-made changes. The wide, amorphous parts of the Charles River near MIT and the Back Bay that were later to be filled in present themselves in an unfamiliar format in this drawing that attempts to reconstruct the region in 1600 prior to European settlement. The fact that the general topography does not imply a place for Bow and Arrow streets to lie is itself telling; the hilly site preexists the streets, and the street layout served development purposes rather than tracing an old stream or natural development.

Source: Chalat, 1990 (Illustration of Harvard Square vicinity

c. 1670)

The initial settlement of Cambridge focused on Harvard University and the land south towards the river. By the 1670s, the development of four decades had already included the construction of Bow and Arrow Streets, then called

The marshy land that originally reached farther north (closer to the site) has been filled slightly to allow for the southernmost blocks. Interestingly enough, this is the first (and among the last) historical maps showing a spring and creek cutting through the properties and emptying into the Charles. Where the creek runs through and alongside the present Bow Street, the thoroughfare widens and angles slightly. This is now the large empty intersection with Mount Auburn Street in front of the triangular block that now defines the western part of the neighborhood. Perhaps the natural topography influenced the placement of this intersection and created a natural boundary not for the street to end, but for the neighborhood to end.

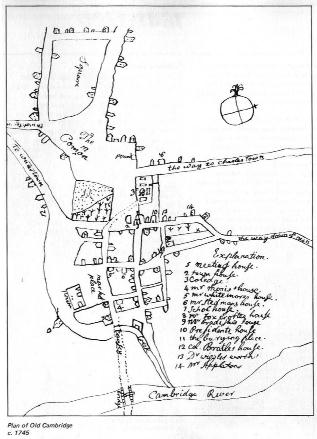

Source: Emmet, 1978 (illustration of 1745 map)

By the eighteenth century, development had extended further around Harvard, but remained localized without reaching towards other parts of Cambridge or its environs. This map from 1745 shows roads labeled not with street names, but with their destinations: Charlestown, and down to the "neck" of land near Cambridgeport. Like many early maps from medieval times onward, the houses and buildings are represented here not in plan, but in elevation next to the street they face. This is an important view because it shows the "Coledge" and its environs not with editorial spelling corrections and graphical modernizations, but as it was viewed and mapped by its inhabitants at the time. For example, the common is not a green space surrounded by streets, but an extension of the street; this is such a small village that circulation paths for animals and people and common spaces for animals and people are willingly interchangeable.

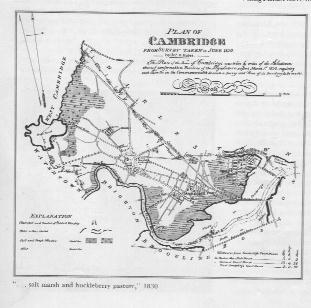

Source: The Cambridge Book - 1966 (Illustration of June 1830 survey by

John

G. Hales)

Cambridge in 1830 is still composed of three distinct villages: East Cambridge, Cambridgeport, and the older village portion near Harvard seen previously. The designation of the area near present-day Central Square as Cambridgeport makes more sense when one sees how far north the river and its marshes extend; the area could have been a primary port had its economy focused that direction. Various maps from this period show the fluctuations in the sea level and the cartographic assumptions relating to marshland; the shallow land grade caused the exact boundary of natural dry land to be somewhat ambiguous. In contrast to areas of Cambridge yet to be filled or made habitable, the neighborhoods near Harvard already have contiguous properties with full development, and the neighborhood in question is becoming quite dense.

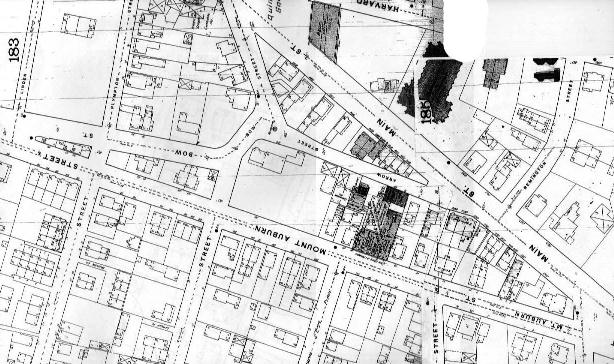

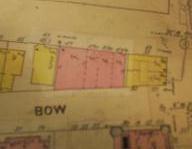

Source: J. G. Hales Survey, 1830, Rotch Map

collection

Zooming in on the 1830 map, the original Bow and Arrow streets have been augmented by the addition of what is now Mount Auburn Street and Massachusetts Avenue. This obscures the shape of Bow and Arrow streets that had been clearer when they were more isolated. Whereas the primary access from the east to the developed area used to be Arrow Street, one now approaches on Massachusetts Avenue to Mount Auburn Street from the triangular intersection at what is now Putnam Square. The development is still well-defined by these streets; the Bow and Arrow street neighborhood is the eastern terminus of the village's dense habitation. As some of the marshes along the river have been filled in preparation for development toward the river, the creek and inlet that extended toward Elliot Street are no longer visible. There is little urbanistic connection to the river, but this is unnecessary at the time for spatial orientation because (1) the village is so small, and (2) there is nothing built that blocks the view south and east to the river from the Bow and Arrow Street Neighborhood.

Relative to the history of other neighborhoods in Boston and in the United States in general, it is unusual that the streets and developable spaces in a city would be well-defined and remain constant since the early 19th century. The buildings and uses have changed, but the pattern of blocks and streets is already in place.

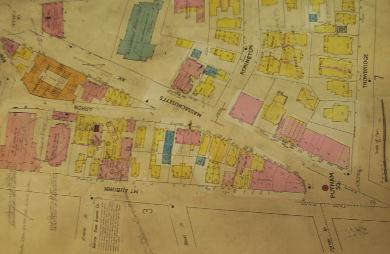

Source: Sanborn 1888 (Rotch Microfilm)

During the period of rapid growth in the mid-nineteenth century, the blocks and streets had already been well-defined prior to changing transportation and development trends. The close proximity of buildings to the street edge made the streets remain narrow just as they are presently. The area northwest of Bow Street is now becoming occupied by Harvard-associated buildings, while buildings to the south and east of Bow Street are generally commercial or residential, with private ownership.

A slight exception is the large L-shaped complex shaded in gray between Mount Auburn and Arrow Streets. This is the Reversible Collar Company building from 1867, an industrial office building that eventually changed ownership and has at various times been a printing company, the Boston Bookbinding company, and architectural offices. Note that the sloping land west of this industrial usage is still vacant and unsubdivided. It is unclear why this was not developed earlier, but it seems to be an effective common space that defines the neighborhood. Since the lot is sloped, it would be one last open area with a slight view of the river beyond, but the land to the south has become more fully subdivided and developed. Consequently, the lots on Massachusetts Avenue and Mount Auburn Streets in this area became residential as Harvard Square expanded. During this period Cambridgeport has developed into the Central Square area with a small City Hall and other civic and commercial uses, so the development along the path to Central is logical. Within the overall context predominated by residences with a few churches, the Reversible Collar Building's large footprint and industrial usage is an anomaly.

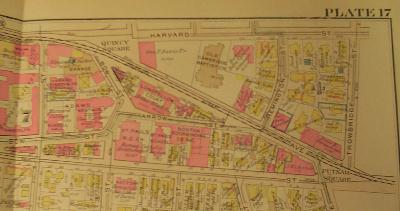

Source: Sanborn, 1900 (Rotch Limited)

The most significant addition by 1900 is the construction of St. Paul's Catholic Church and the education building next door. In the largely Protestant American colonies, it is telling that it took nearly three centuries before a Catholic church was able to be formed within sight of Harvard. As more immigrants came to the United States, class conflict existed between older Protestant immigrants and newer Catholic, predominantly Irish, poorer immigrants. Therefore, built edifices such as the large, brick, rather imposing church in this neighborhood are symbolic of how the more recent immigrants became more established in this already historic neighborhood. The height of the campanile also asserts a presence to the Harvard Square area as a whole.

Meanwhile, the Harvard-owned and other buildings on blocks adjacent to the neighborhood have become denser and somewhatmore commercial on Massachusetts Avenue. This 1900 map also has a correction to show the 1916 construction of the pentagonal Longfellow Court Apartments north of Arrow Street. This reinforced concrete building shows a neighborhood transition to include not just individual houses but also multifamily, multistory housing units.

Source: Sanborn, 1930 (Rotch Limited)

By 1930 the Longfellow Court Apartments have been completed, the land east of the Reversible Collar building has become an auto service area, and the corner at Putnam Square has changed owners. These two changes are significant and representative of the few ways the twentieth century has affected the neighborhood.

First, the rise of the automobile as a mode of transportation created the new building typology of the service station. Its placement near Harvard square and Massachusetts Avenue is important because accessibility and visibility are important for such service stations to survive economically. Moreover, there are no service stations anywhere in the immediate vicinity of Harvard Square remaining, so this would have been a necessary convenience as Harvard Square traffic changed to accommodate myriad automobiles as well as pedestrians and public transportation. The automobile service station remains situated in the midst of small, residential owners, and that may have strained the relationship of property owners in the neighborhood, as it remained a possibility that such commercial and industrial uses would envelop larger and larger tracts of land.

As it turned out, the only major consolidation of property occurred at the east end of the neighborhood, the triangular sliver of land facing Putnam Square. This became the most public of the neighborhood's corners, and its high visibility made it apt for commercial development larger than single storefront shops. The change to a larger commercial use before 1930 may have met difficulties during the Depression, but even as the buildings on that site changed, the use remained commercial.

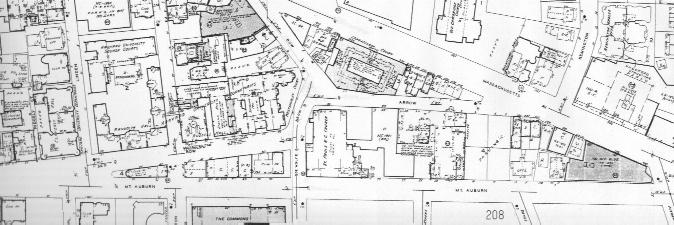

In the 1988 map, the most fascinating element is the sheer lack of change. During the period in the mid-twentieth century when changes in transportation, urban life, and economic development were rapid and had far-reaching consequences, the blocks and streets adjoining the neighborhood changed. In the relatively insular Bow and Arrow Street area, however, there were no appreciable changes in over five decades to the streets and their buildings except for the office building at the eastern corner. This is rather profound; aside from the detail changes of the past fifteen years, the body of this neighborhood is a great place to study what it felt like to inhabit an urban space in the 1920s or even earlier. In contrast to Harvard Square proper, or any of the parts of Central Square/Cambridgeport or East Cambridge that existed in the earliest settlement maps, this place has changed the least of almost any part of Cambridge outside of Harvard Yard.

Here too is an example of the boundary issues mentioned in the introduction. Previous Sanborn maps placed the page crease or end of the map at the western end of Bow Street, where it creates a triangular extension of the neighborhood towards the intersection with Mount Auburn Street. While the neighborhood has retained visual coherence, it is now always split down the middle through Bow Street in each of the more recent Sanborn maps, and its printed on nonadjacent pages. This is partly because of printing space but shows a disjunction between the apparent separation in print form and coherence in built form.

Source: Sanborn, 1996 (Rotch Reserve)

The most recent Sanborn maps in the Rotch library are from 1996, and there have not been any major changes since then. The maps from 1991 and 1996 show the insertion of the new Harvard Catholic Student Center between St. Paul's and the Reversible Collar building in the early 1990s. The mystery of the vacant lot, to be examined in detail below, is answered in part by these Sanborn maps, which narrow the window of demolition to between 1988 and 1991. At some point in those three years, the service station and the buildings on Mount Auburn were demolished, and the area became a parking lot. Nevertheless, it is still illustrated as four independent vacant lots. A few of the residential areas have changed to accommodate small shops and food places on the ground floor, such as the new creperie that began the initial interest and investigation into the site.

Source: Sanborn, 1900 (Rotch Limited)

Editing

An unforeseen issue I dealt with through the process of researching old maps is one of editing on the physical maps themselves. Library materials are notorious for becoming an inadvertent palimpsest, where comments by past readers and researchers are scrawled alongside the original printed material. In these maps such markings, often penciled notes relating to other research materials, are present in great number and attest to the frequency of use through the years. With the Sanborns, however, there are two added layers. First, there are printed notes, largely relating to the security provisions for each major building, such as how many night watchmen and their duties; such notes now describe electronic systems by ADT and the like, but in the same graphic style and font as a hundred years ago. This layer of highly clarified text gives insight into what was deemed important public knowledge for security, fire safety, and the like.

The second added layer is more visually challenging: changes to the built environment have been reprinted on white paper and pasted into the maps. For example, on the 1900 map the Longfellow Court Apartments are shown as built, with a construction date of 1916. This was initially confusing and shows that the physical pages of the maps were changed, piece by piece, through the years between 1900 and 1930. Part of this is a pragmatic solution: it was more economically and functionally feasible to insert the changes rather than reprint the entire volume. This is curious considering the number of changes and the great care required in making minute changes to blocks. Moreover, this shows a value judgment for the Sanborns as historical documents; during the early twentieth century it was more important for them to be updated and correct than for them to retain a historic purity that froze a moment from a specific year. What gives the reader a clue to the anachronism of the maps (besides obvious dates) is the slight color change of the paper, as shown in the above photograph. The difficulty this presents is that one is less able to dissect the various historical layers because of the physical paper layers and the glue between them.

Sources: Sanborn, 1988 and 1996

Deleted Scenes

From the late twentieth century, printing techniques and the use of Sanborns as historical documents allowed maps to be published more frequently, and no such difficulties of pasted paper are present. Focusing more specifically on the now-vacant lot between Mount Auburn and Arrow Streets, there are specific conditions of erasure in the built environment. As mentioned in brief above, the maps from 1988, 1991, and 1996 show that the service station and houses on Mount Auburn Street continued their existence until between 1988 and 1991, but have remained unchanged in the 1990s and to the present.

One important note is that this is not that long ago. Whereas the neighborhood occupants in part one described the demolition as occurring many years ago, it has only been about a decade. Thus the relative time of absence seems longer in an emotional sense than the actual chronological time has been. The absence of redevelopment remains an unresolved question; perhaps the environmental difficulties of old service stations have caused the land to become a brownfield.

Second, the existence of the buildings in the maps does not fully describe their condition. The variety of uses local people described (motorcycle store, Grocery) are unaccounted for in the maps, but there may have been variations that were not fully documented. The buildings may have been run-down or nearly vacant for several years prior to their demolition depending on how the landowners and city treated the situation. There is no description of quality present in these rather impersonal map views, and it remains a question as to the circumstances that propagated the vacancy. Moreover, the discontinuity in the grade between Arrow and Mount Auburn streets that occurs near the lot line and the wavy sloping drainage pattern of the parking lot, are not described in the Sanborns, so the topographic story of the site is still somewhat obscured in this highly localized example. The gentle hillside with a view of the river in the 1600s has now been broken into two planes, a rare vacant lot in this neighborhood that awaits desperately a future use.

Resources containing primary source maps:

Cambridge Editorial Research, Inc.: The Cambridge Book - 1966. Published by the Cambridge Civic Association.

Chalat, Josef Yul: Connections to the City: A Spatial Structure for New Perceptions of Harvard Square. (c) 1990, MIT M.Arch. Thesis.

Emmet, Alan: Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Changing of a Landscape. (c) 1978 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Boston, Volume 6. New York: Sanborn Map & Publishing, (c) 1888.

Cambridge, Volume 2. New York: Sanborn Map & Publishing, (c) 1900.

Cambridge, Volume 2. New York: Sanborn Map & Publishing, (c) 1930.

Cambridge, Volume 2. New York: Sanborn Map & Publishing, (c) 1988.

Cambridge, Volume 2. New York: Sanborn Map & Publishing, (c) 1991.

Cambridge, Volume 2. New York: Sanborn Map & Publishing, (c) 1996.

Other Resources:

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier

All Images (c)

2001-2002

David M. Foxe, unless otherwise notated. All Rights Reserved.

|

|