The Rose Kennedy Greenway and North Station, taken on February 28, 2013 / The North End and Thacher Street, taken on April 16, 2013

The Rose Kennedy Greenway and North Station, taken on February 28, 2013 / The North End and Thacher Street, taken on April 16, 2013

A place has so much depth to it that can be seen just by looking at a picture: what it has been, where it is, and who will use it next. As Hayden says in The Power of Place, “authors… rely on ‘sense of place’ as an aesthetic concept but often settle for ‘the personality of a location’ as a way of defining it.” (Hayden p. 15). Everything that has happened on or near a location contributes to this personality. In the picture on the left, there is a wide open expanse with green grass and trees, tall new buildings under construction, a train station, and an underground highway coming up to cross the Charles on a magnificent bridge. The picture on the right is very different. It shows evidence of a couple street breaks, tall buildings squeezed together, old renovated apartment buildings, narrow streets with lots of sidewalks, and a pizzeria and some other small shops on the ground floor of the apartments. These two pictures tell two different stories about their history through each layer of remaining traces from a specific time period. Analyzing these layers together can show trends that may have caused each half of my site to change separately from the other half.

The main trend in my site over time is the definite split between the eastern and western halves. They contrast greatly in both land use and changes. The eastern side contains part of the famous North End, rich in culture and very stable over time. Not much has changed there; many buildings have been there since the early 19th century or before, and the overall structure and feel of the area has stayed the same as well. The streets are narrow, the buildings are clustered together tightly, and people still live in small apartments above or near their small, family-owned shops and restaurants. Conversely, the western side contains the Rose Kennedy Greenway and the MBTA North Station, and is an excellent example of how the different stages of the transportation revolution affected areas both physically and socially. Freight trains, passenger trains, multiple subway lines, and highway I-93, both elevated and underground, have existed here. Many of the effects of these changes are hidden by looking at the current site, but can be easily explored through historical maps. These changes explain fully why the area looks like it does today.

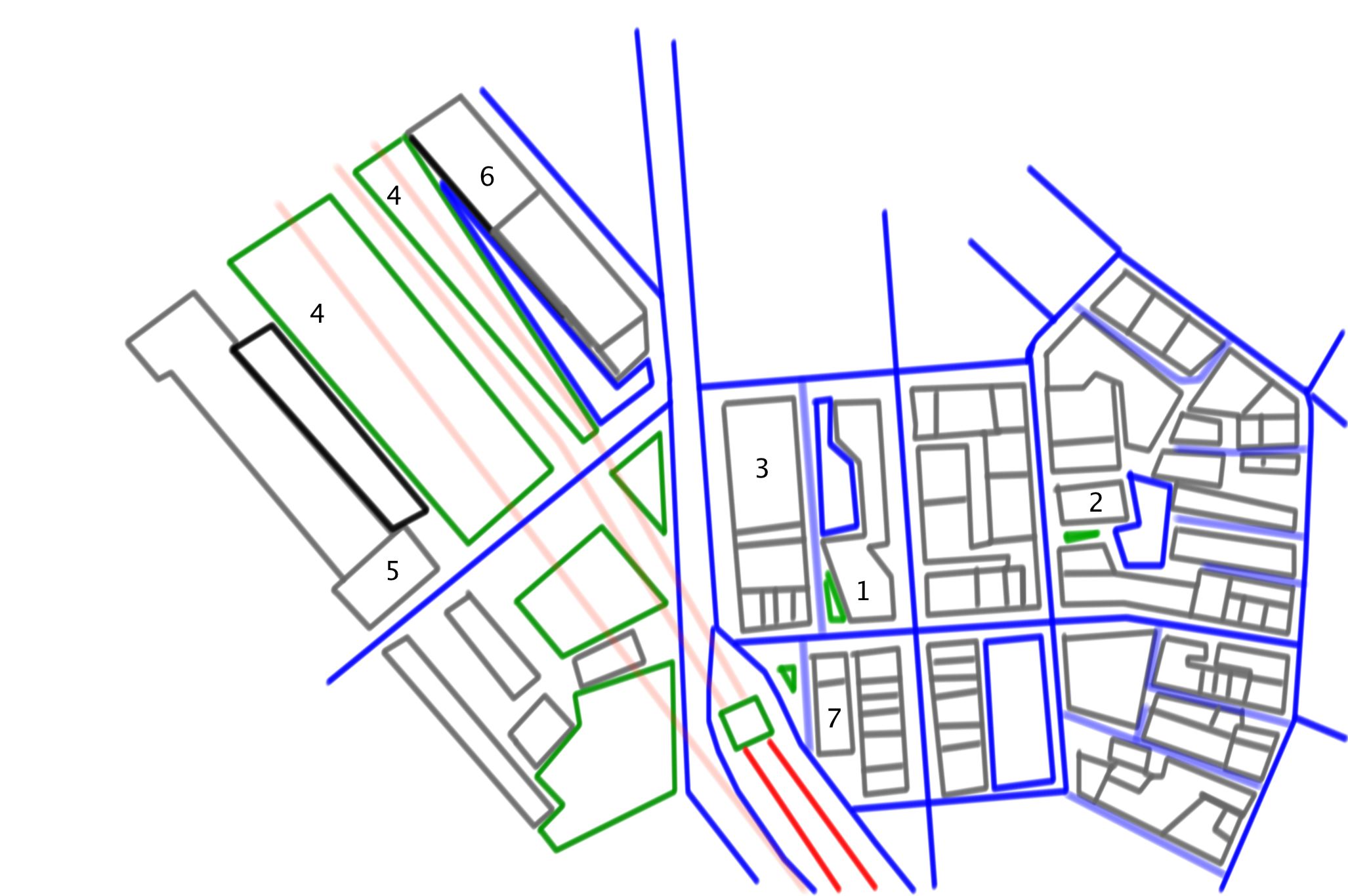

Figure 1 – an outline map of my site with

key artifacts numbered

Figure 1 – an outline map of my site with

key artifacts numbered

In Figure 1, I have made a current diagram of the major features of my site. I selected the most important artifacts that exhibit different layers or trends. Number one is St. Mary’s Church, which is important because the institution has been there for so many decades as a mark of deep-rooted culture. Number two is now the Knights of Columbus, a volunteering and charity club for men. Before its current use, it was a Jewish Synagogue, but before 1886, it was the Home for Little Wanderers. This home was a refuge for orphans and homeless children and is now the name of a statewide chain. Space four is the Greenway, and buildings three and six, as well as other areas around the Greenway, are brand new buildings that are unfinished or still for rent. Number five is part of North Station, a transportation hub that serves two T lines and three commuter rails. Number seven is a group of somewhat newer apartments. Most of the unlabeled buildings on the eastern side of my site have existed for many decades, some since the early to mid 19th century. Many of these are triple-decker apartments and are largely residential, often with small commercial businesses on the ground floor.

The Rose Kennedy Greenway where an onramp to I-93

goes underground, with downtown Boston in the background

The Rose Kennedy Greenway where an onramp to I-93

goes underground, with downtown Boston in the background

The most significant artifact on my site is the Rose Kennedy Greenway. It takes up a space as wide as a city block and has nothing on it but grass and trees. As can be inferred from the picture, it lies directly above the underground tunnel of I-93 where the Central Artery used to be before 2006. The Greenway is a very evident trace of the previous elevated highway. Through its spacious grandeur, it serves as a monument to the giant concrete monstrosity that used to be in its place.

The Greenway with North Station and construction

in the background

The Greenway with North Station and construction

in the background

The Rose Kennedy Greenway is a healthy green space that improves the beauty of the area and allows for a community-gathering place and new growth around it. The construction in the picture is only possible due to the extra space made by the Big Dig. There are several brand new buildings, some of which are still not in use yet, that can only exist now due to the new space that became available when the Artery was torn down. In addition, the removal of the Central Artery drastically improved the area’s aesthetics, so the value of the area around the Greenway has increased greatly because of its visibility.

The Greenway may be a place for new growth now, but all the empty space was originally filled with old buildings similar to those a few blocks to the east. It was put in place because the Central Artery disrupted the normal aesthetics and traffic flow in the city. The purpose of the underground highway was to reduce congestion in central Boston and reduce travel time for commuters. This was also the purpose of the Central Artery when it was planned, but it did more harm than good by forcing blocks crammed full of North End culture to be demolished and separated the North End from the rest of Boston.

Advertisement billboards and signs on the tops of

tall buildings

Advertisement billboards and signs on the tops of

tall buildings

Other traces of the Central Artery can also be found. Billboards and store signs like these can still be seen on the tops of buildings. This seems strange now, but when the highway was still above ground, billboards on top of buildings were popular because they were very visible from the highway. These remnants of the monster that used to loom over Boston point to what must have been a drastic physical change when the Big Dig put the highway underground.

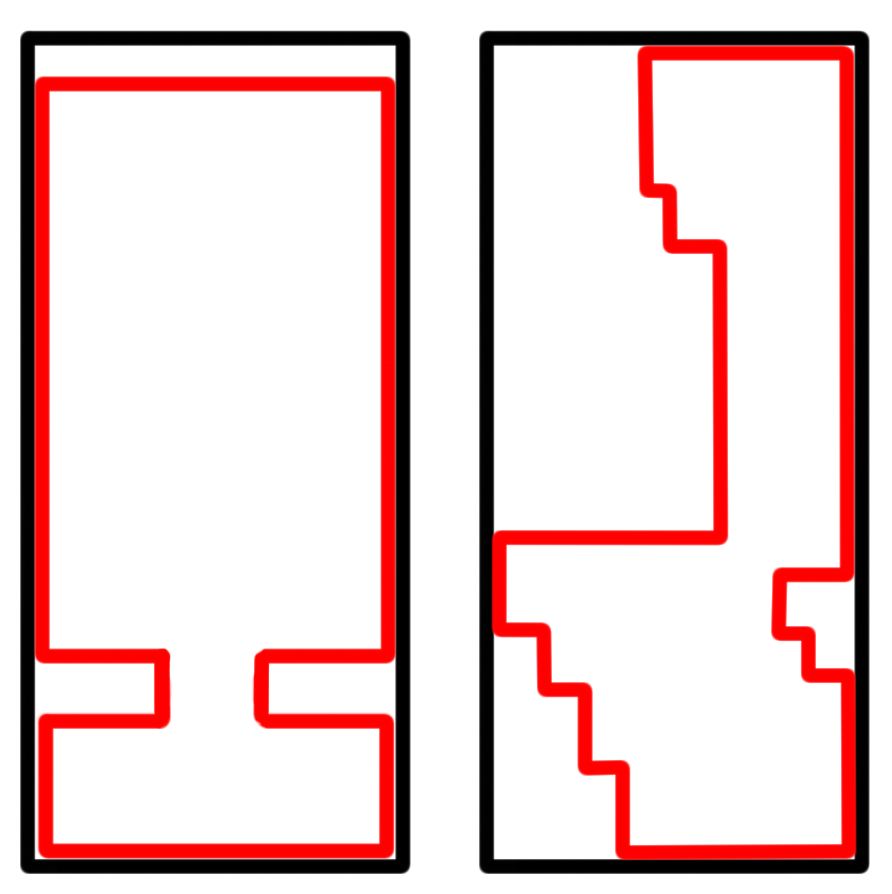

St. Mary’s Church on Endicott Street through the

entire 20th century compared to its current shape

St. Mary’s Church on Endicott Street through the

entire 20th century compared to its current shape

St. Mary’s Catholic Church is an artifact that predates most other traces on my site. It has been on the corner of Cooper and Endicott Streets since at least 1867, where it is shown on a Sanborn map. The church quickly grew until it owned the entire block amongst the otherwise tiny properties surrounding it, and used the same building for about a century. At some point, presumably in the late 20th century, the church rebuilt a new chapel in the same location in conjunction with residential apartments sharing the same building.

A long row of high-rise apartments with small

Italian shops and restaurants on the ground level

A long row of high-rise apartments with small

Italian shops and restaurants on the ground level

There are a large number of small, family owned pizzerias, bakeries, and Italian restaurants in the area that have been there for many years. Some of the buildings they own have existed since the area was first settled. The North End is known for these remarkably delicious eateries, and their existence can be explained by the surrounding culture. Most parts of Boston changed with the automobile revolution in the early to mid 1900s due to the popularity of the automobile since people could drive further for more convenience while shopping. While many areas lost corner stores and small cafes to a few supermarkets and chain restaurants, the North End kept its narrow streets and small, deeply cultured character.

According to Guild Nichols, many Italians are Catholic, and the Italian culture has persisted in the North End ever since its first settlement (Nichols). Thus, the prolonged survival of St. Mary’s Catholic Church in the same location for so many decades while many other churches in the area did not stay long may be related to the trend of a high Italian population.

The people who lived in the North End had a rich culture and all the things they needed to be happy. The area still houses some of the best and fanciest bakeries, restaurants, and specialty shops in all of Boston. The reason there are no parking garages and Costcos in the North End is because the residents never moved out to suburban areas; they stayed right where they had always lived, in small apartments above their shops.

This cultural consistency has been so penetrative in my area of the North End that even surrounding physical upheaval, like the erection of the Central Artery only a few blocks away, did not change its personality. According to John Mirabella, the elevated highway caused people to dislike commuting between North and Central Boston, which made the North End a highly undesirable place to live and became isolated from the rest of Boston. In addition, it seems that people were also somewhat racist towards the Italians and did not want to live in an area with a high Italian population (Mirabella).

During the urban renewal era of the 1940s- 60s, the North End was not a priority region and was considered an undesirable place of residence, and thus never underwent any reconstruction. This stable but low economic status is probably why very few blocks on the eastern side of my site have had a wide variety of uses over the decades, only those along Washington and Haverhill Streets on either side of the Greenway where there are currently brand new buildings, because they were directly affected by the construction of the Artery. The rest of my site was kept consistent by the deep-rooted Italian culture and the fact that wealthy families and developers had no desire to move there and change things. It is unlikely that the North End will change dramatically in the future because the culture and atmosphere is popular with Bostonians.

A long line of variously styled, renovated 19th

century apartments curves due to street breaks

A long line of variously styled, renovated 19th

century apartments curves due to street breaks

Another trace of the North End’s past is that many of the streets are very narrow and difficult to navigate with cars. Many of the streets look narrower than the sidewalks on either side of them. Much of the traffic in the area is pedestrian traffic because it is easier and more convenient for people to just walk to a destination since things are so close together. Many buildings have multiple tenants, both residential and commercial, and structures are often so close together that at first glance they appear to be one huge building taking up a whole block. This can be explained by the area’s early history when foot and equestrian traffic were the primary modes of transportation, and the fact that the area has stayed physically similar to how it was over a century ago.

The Haymarket T Station sits at an intersection

of many sidewalks because it is a center of pedestrian traffic for the area

The Haymarket T Station sits at an intersection

of many sidewalks because it is a center of pedestrian traffic for the area

A major artifact that has been a part of my site for many decades is North Station and the nearby Haymarket Station. Haymarket was originally the Canal Street Station, but has since moved several times. There new entrance to North Station appears to be under construction on the western edge of my site. The continuous presence of the passenger train stop in the area despite its many slight changes in position indicates a need for transportation to my site. The MBTA website says that around 1900, the rapid transit line was added to the Canal Street Station (MBTA). At the time, there was an abundance of industrial companies nearby in my site, particularly along what is currently Washington Street. All these companies needed workers that had to commute from a faraway home. Since the North End had such a stable culture and population and the surrounding area was filled with industry, there was not really room for new residents to move in for work purposes.

The introduction of the subway system made commuting much faster since workers did not have to rely on streetcars winding through the heavy traffic in the narrow streets. It also allowed for commercial businesses to thrive in the area by the 1920s since it was so much easier for visitors to travel there. One example of a resultant trace is the strip of shops and eateries along Washington Street. The part of my site along the Greenway is still heavily commercial as a result of this change.

North Station, just north of my site, services

the Green and Orange T Lines, as well as three commuter rails

North Station, just north of my site, services

the Green and Orange T Lines, as well as three commuter rails

North Station brings in people from two MBTA lines as well as three commuter lines. With all the shops and eateries nearby and TD Gardens above the T station, many visitors use it for recreation. The new building was built just recently as the Big Dig finished because there was a need for better transportation since the Greenway gave the area greater aesthetic attractiveness.

North Station, though now a transportation center, was once important to industry, although it was in a slightly different location then. The industry that helped shape my site was possible for several reasons. Firstly, when the Mill Pond was newly filled in, there was an abundance of space that was perfect for new development of large factories and warehouses. Secondly, the freight train that came across a bridge over the Charles River allowed for easy transportation of materials and products. This need for a nearby freight stop is what caused the Canal Street Station to become so popular and heavily used until the advent of the automobile.

There is a great disparity between the majestic open area with fresh grass and spacious skies and the rows of picturesque bakeries and pizzerias nestled together with old brick architecture and dirty allies in the back. This sharp contrast makes Washington Street seem like the Great Divide of my site because it separates the Greenway from the North End. It seems strange that an old Catholic Church and long rows of tiny apartments above little shops and restaurants run along narrow streets that abruptly hit a wide open space with tall, shiny buildings and grass, and trees. But it makes sense that the same Artery that caused the open grassy wound of the Greenway helped to protect the culture and economic status of the North End, and that the confined nature of the North End’s culture is what caused the Greenway area to change so drastically with the need for transportation. These two halves of my site, though definitely separate, have influenced each other in complex ways, and will continue to as the popularity of the North End’s Italian attractions combine with the new beauty of the Greenway to make my site a pleasant destination for visitors.

Works Cited

Mirabella, John. "The North End: From Isolation to Transformation, the Construction and Deconstruction of the Central Artery." Wordpress. Web. 23 Apr. 2013. <http://johnmirabella.wordpress.com/the-north-end-from-isolation-to-transformation-the-construction-and-deconstruction-of-the-central-artery/>.

"History." MBTA. Web. 23 Apr. 2013. <http://www.mbta.com/about_the_mbta/history/?id=962>.

Nichols, Guild. "Part 5: Boston's Little Italy." North End Boston. Web. 23 Apr. 2013. <http://www.northendboston.com/2010/09/north-end-history-volume-5/>.

Works Consulted

Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1867, 1885, 1895, 1908, 1929. Digital Sanborn Maps. ProQuest. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000001.htm?CCSI=254n>

Bromley, G. W. Atlas of the City of Boston, from Actual Surveys and Official Records. Map. 1883, 1902. Dome. MIT. <http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999>