South Station / Dewey Squarephoto: © Leslie Jones, 1956 - Boston Public Library

Week 13, May 23 2014

After having presented a summary of my findings as part of this project on Wednesday, now seems an appropriate time to reflect on the project as a whole.

I did not realize at first how the first five presentations that were given on Wednesday related to one another. They all had such a different present state, a different history, a different origin. But during the in class discussion after we had all finished the puzzle started falling together. For the whole semester, I had been looking at South Station: its industry, its history of people moving in and out, towards the neighborhood down the street, the suburb, or another city far away. But I was zooming in on one end of the line: all these newly developed methods of transportation, while certainly reshaping Dewey square, also drastically introduced or changed neighborhoods on their path. The streetcars and subways I saw appearing also appeared in Coolidge corner or Davis Square, but with a very different impact. Functions I saw shifting away appeared on the other end of the line.

I was also surprised to see how similar the Bulfinch Triangle area was in its early days compared to South Station. The railway terminal there brought with it its industry, blacksmiths, liveries and the like much like it did in its southern counterpart. Yet today these two locations in Boston are nothing alike. This change in development can probably be attributed mostly to a single decision from the very end of the twentieth century: centralizing Boston's passenger railway transport in South Station. It keeps impressing me how much influence a single decision can have on an urban environment.

The following sixteen presentations will without doubt reveal more and more broader patterns that were not directly visible from our sites' focus.

Week 12, April 26 2014

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, written in 1961, Jane Jacobs writes: “Of course [city planning] stagnates. It lacks the first requisite for a body of practical and progressing thought: recognition of the kind of problem at issue.” Jacobs refers to city planning being treated with statistical problem solving techniques, without recognizing its organized complexity known from the biological sciences.

I think it is extraordinarily important to reflect on this issue today. Developments of the last two decades, in particular in the field of computational technology, allow for revolutionary, new problem solving techniques to be applied. Because at the basis of every problem in organized complexity lies an easy to model decision making process. What we have failed to realize in the domain of urban planning is that the sum of these lower-level decision making processes is an incredibly complex system that can indeed not be modeled by ordinary probability and statistics, or single mathematical laws.

Yet I strongly believe that we have the technologies for large-scale prediction of the consequences of urban planning decisions at hand. Today, we can run system simulations that simulate thousands of individual-based decision making processes simultaneously. The way they interact as a result of this simulation is not otherwise predictable.

A simple example is that of a traffic system. Traffic, like urban planning as a whole, is a problem of disorganized complexity. It is impossible to predict its behavior based on ordinary probability theory or mathematical laws. Yet it is very straightforward to predict the behavior of an individual on its commute from home to work: he or she will generally follow the fastest route, at a fixed time of day, taking in account the other individuals trying to the same (i.e. avoid traffic jams). Today's technology allows of to run thousands of these single processes (one car) simultaneously. The patterns that emerge reflect what we see in daily life to an incredibly accuracy. Predictions like this were impossible to make two to three decades ago.

Learning to apply large simulation techniques to urban planning is a domain I am personally very interested in. It is definitely the reason I am taking this class (interestingly enough, as the only Electrical Engineering and Computer Science student this year). The Jacobs reading made me realize that the lack of applying readily available knowledge to urban planning has been a problem for decades – and one I can only try to help solve.

Week 10, April 12 2014

Monday's class provided an opportunity for me to briefly present the work I've been doing exploring the history and current situation around South Station and Dewey Square. Most importantly, I got to see the different insights fellow students have on very similar, adjacent or even overlapping sights. The details that meet one's eye are subject to the individual. Therefore every one of us notes possibly similar, but distinct aspects of urban life around our sights. The influence of changes we observed in our own sites obviously extend beyond our arbitrary boundaries, in neighboring sites but possibly even up to miles away. Seeing these changes was exciting.

Wednesday's class gave an interesting insight in the West Philadelphia Landscape Project. I found it interesting to learn how the change of function of a certain site (with settling industry, etc.) changed social structures. The first part of this weeks reading, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History by Dolores Hayden, elaborated on exactly this topic. Her description of “place” puts the observation of the urban landscape into social and general (aesthetic, sensory) perception. I think this is a powerful concept that has been a basis for all the work we did in the context of this class. Hayden's history of a place is a history of those observations that we have been trying to make on our own sites. It is a history of projecting our current observations backwards through time time to understand how citizens back then used and perceived a given space.

I will finish the last part of the Hayden reading by tomorrow, to complete the basis for our last assignment, on Traces and Trends. I am eager to find out what new discoveries I will make around South Station, with the now studies history of the site in the background.

Week 7/8, March 30 2014

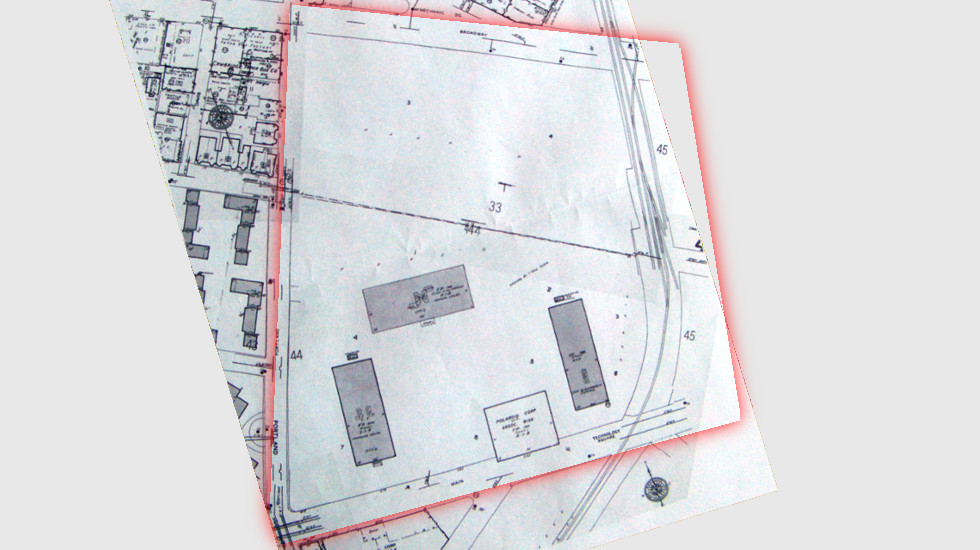

This week's main focus has been applying the research we did on our class site in week 6 to our own site. For the Dewey Square and South Station area, the Sanborn Fire Insurances proved extremely resourceful. Accurate maps available from every decade show the site's evolution, its shifting use of transportations and its changes in industries. (large, high-detail maps of the site that I have assembled from sheets of the Sanborn maps are available below)

The break also proved a good time to continue reading Kenneth T. Jackson's Crabgrass Frontier. One aspect of suburbanization that Jackson describes is the duality between transportation and desire for a quieter environment. Is it the developments in transportation technologies that enabled reaching out further into the countryside, or is it the desire of the wealthy to reach out that drove development of more comfortable and affordable transportation?

Exactly this development is extremely applicable to the history of Dewey Square. At first I struggled finding the relevance of a work entirely treating suburbanization, when my site was part of even the earliest settlement in Boston. But then I realized that “moving people” is always a system that goes both ways. For transportation to branch out into the open, the city has to provide a hub where everything connects together. And this is exactly was South Station was and is for Boston.

The original railroad facilities at the site were laid out along the wharves, transporting only cargo. A continuously expanding demand for passenger railways then caused the construction of the south station railway terminal in 1899, now coming from the south in order to connect with people, not goods. By 1989, a streetcar can be found on Atlantic avenue, which was later elevated to make room for the automobile.

Another domain to explore is the site's industrial development. Where in 1867 a high concentration of Blacksmiths can be found around the more southern streats in the area, by 1885 the leather industry is dominant (this explains why this part of Boston is named the “Leather District”).

The Fire Insurance Atlases are not available after 1938. One of my goals for the next few days will be to find resources that cover the last half century. Developments like the Central Artery and Great Dig have strongly shaped Dewey Square, and deserve a good amount of attention.

Week 6, March 15 2014

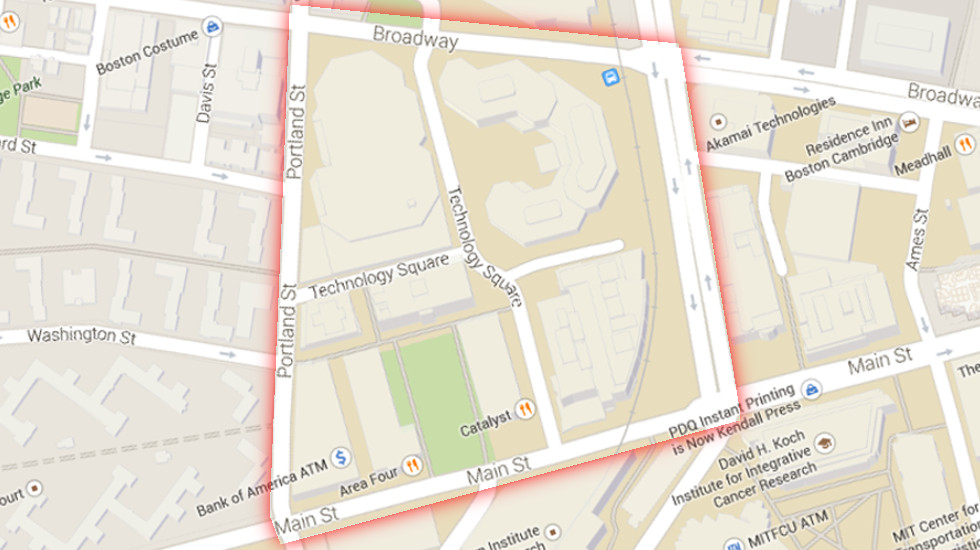

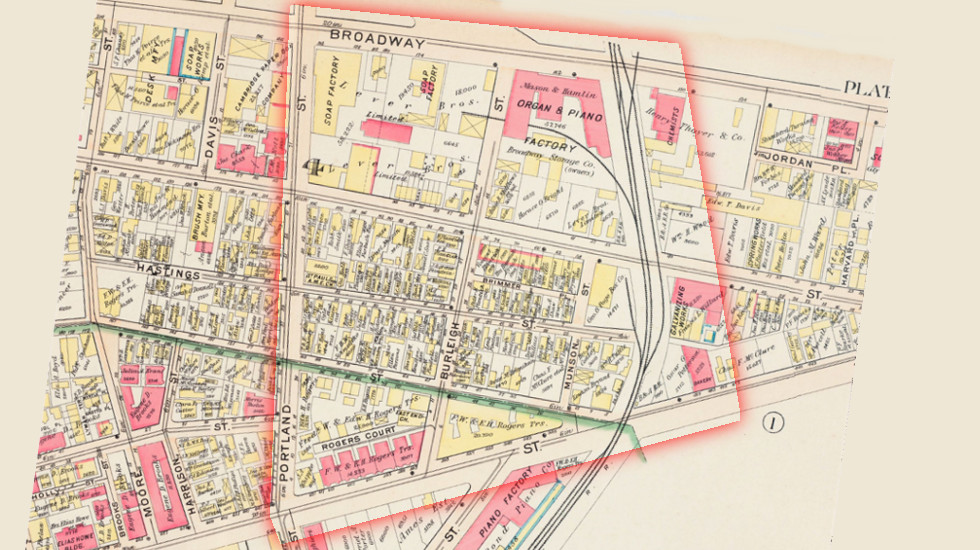

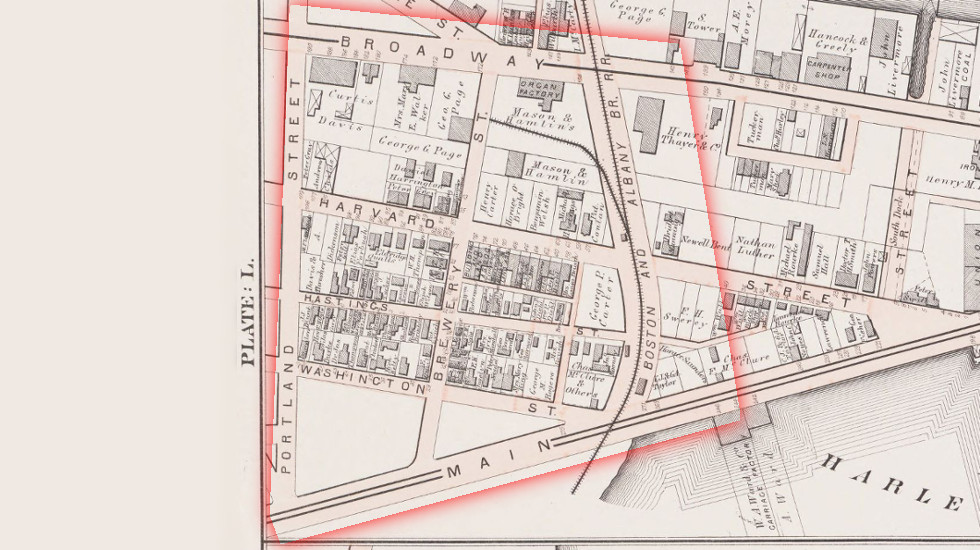

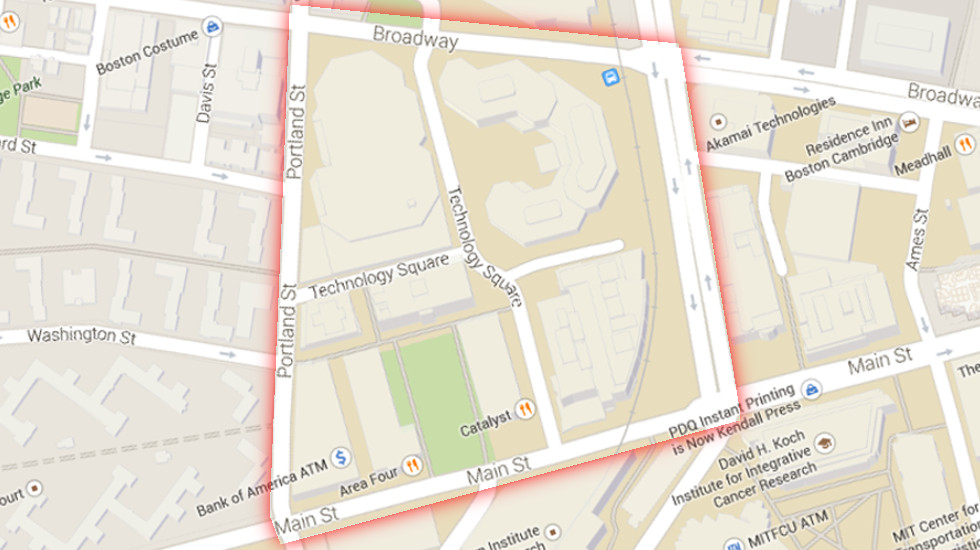

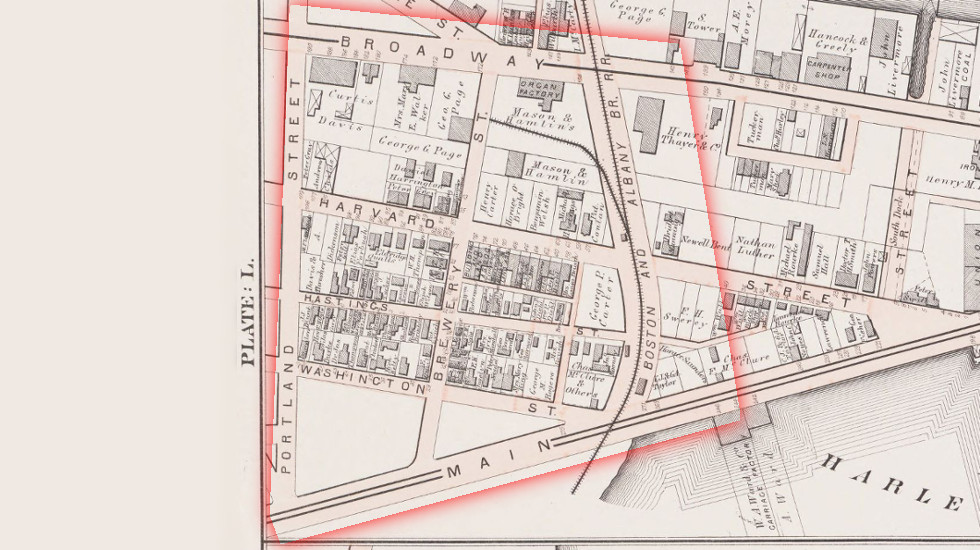

In class on Wednesday this week, we analyzed the evolution over the past century and a half of a section of our common class site in Cambridge. Our site was what is known today as Technology Square, a recently developed research- and office building area in Cambridge's Kendall Square area, situated between Broadway, Portland St., Main St, and Galileo Galilei Way. In order to understand the evolution of this small plot of land, we looked at a series of 6 maps describing the area as it appeared in 1873 up to today.

The interactive map view below allows the site we analyzed, highlighted and identically positioned on all maps we used, including their sources.

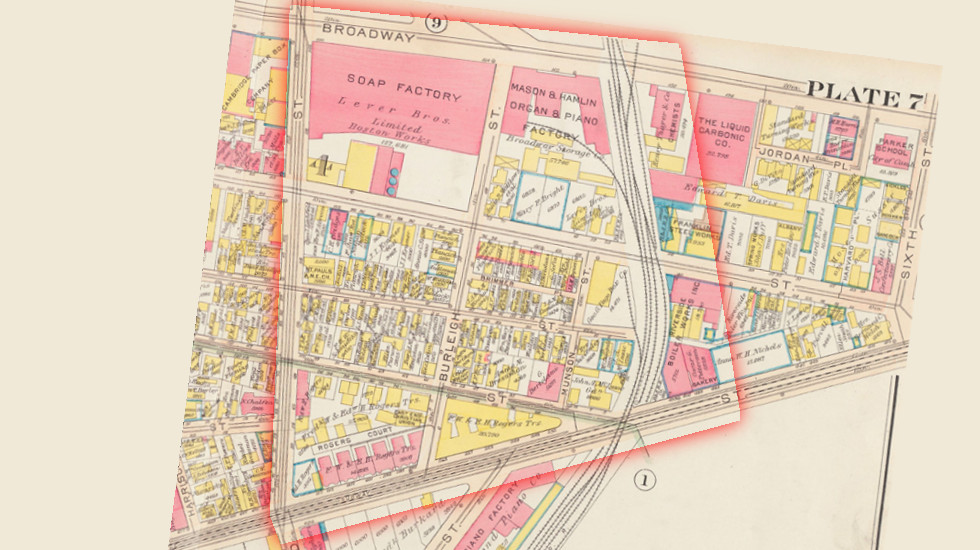

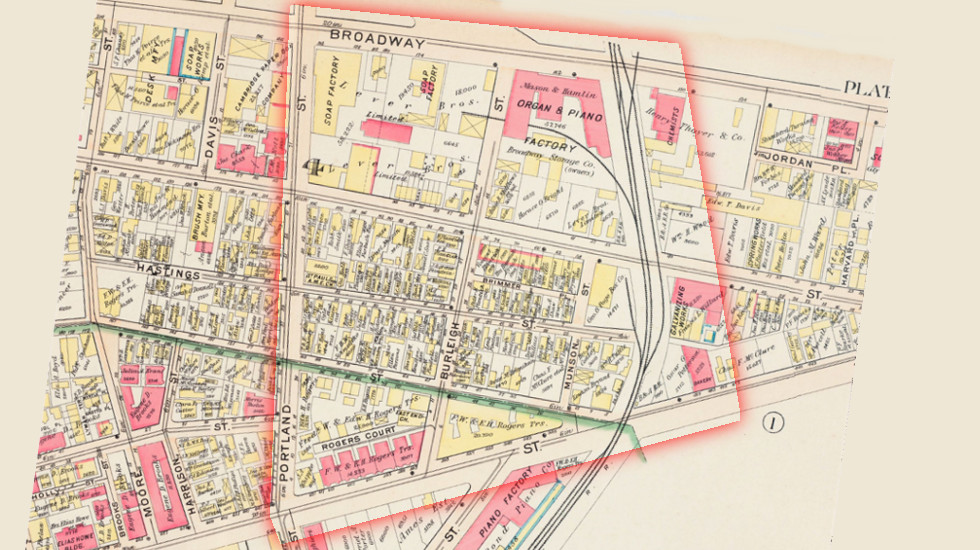

On the oldest map, dating from 1873, the immediately looks significantly different than it does today. The roads are aligned with Broadway, whereas today they are aligned with Main street. Street layouts are one of the most persisting properties of urban areas, which means something unusual must have happened. The land use of the area is also significantly different than it is today. The area between Washington and Harvard Street is a residential area, with isolated single family homes, showing the names of the owners. Some industry can already be found below Broadway, with the railroad extending into the Mason & Hamlin's Organ Factory.

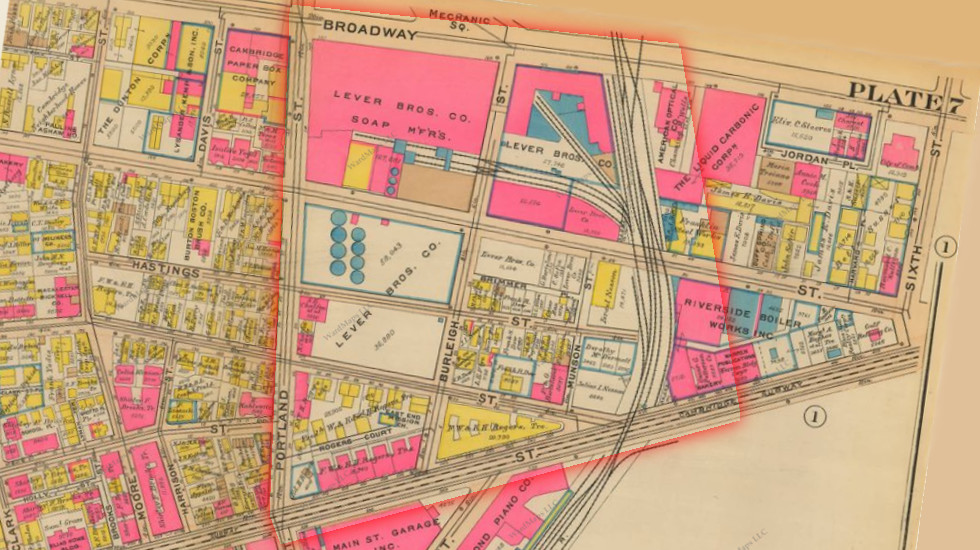

In 1903 we can see that the land between Main St and Washington Street is now developed. The residential area remains, but the industrial area north of Washington street is clearly expanding. Notice how the Lever Brothers Soap Factory has settled in the most north-west block in the site. The railroad now features double tracks, and the branch is extended to the soap factory.

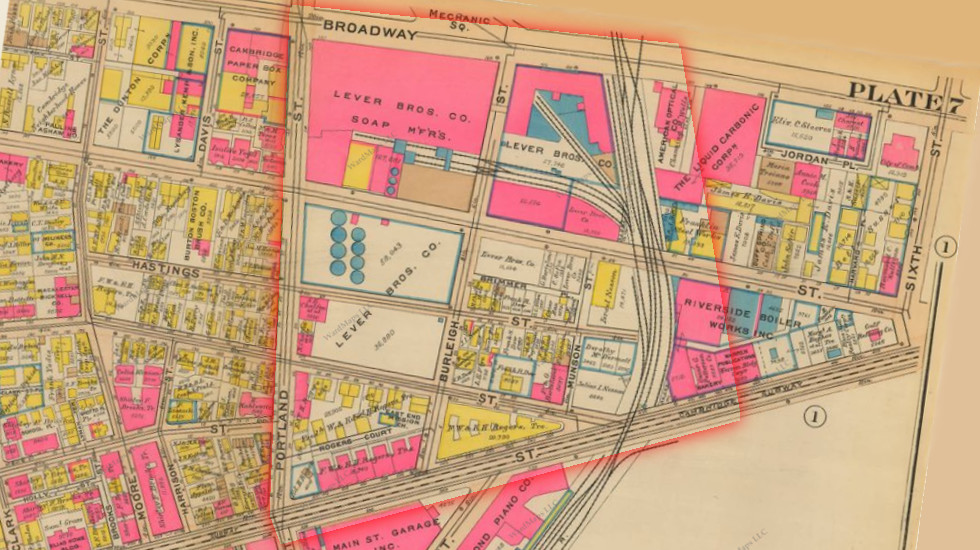

The 1916 map again shows more industrialization of the northern part of the area, and expansion of the railroad running north-south.

Notice how in 1930, the Organ and Piano factory has ended business in this area, and the Lever Brothers Soap Factory has taken over their entire site. Most importantly, a large part of the former residential area has been acquried and demolished by lever brothers. The area around the railroad is now losing its residential function.

By 1970, the look of the entire area has changed drastically. It turns out that Lever Brothers merged with the Dutch margarine manufacturer Margarine Unie to form one of the biggest soap and food concerns today, Unilever. In an effort to modernize their production facilities, the Cambridge factory was abandoned in the 1950's. By 1970 the site has been completely cleared of buildings and roads, and shows three office buildings: a clue to its new purpose.

Today in 2014 the site has been entirely repopulated, temporarily owned by MIT and real estate companies. It now hosts large office and research buildings.

Feel free to explore more changes using the interactive map view below. The methods we used during Wednesday's class are eye-opening. I hope to be able to do the same thing for the South-Station site I chose soon.

- 2014

- 1970

- 1930

- 1916

- 1903

- 1873

© 2014 Google

Source unknown

Bromley, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co., 1930 - Wardmaps LLC

Bromley, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co., 1916 - Harvard University Library

Bromley, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co., 1903 - Harvard University Library

Hopkins, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.M. Hopkins & Co., 1873 - Harvard University Library

© 2014 Google

Source unknown

Bromley, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co., 1930 - Wardmaps LLC

Bromley, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co., 1916 - Harvard University Library

Bromley, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co., 1903 - Harvard University Library

Hopkins, Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Philadelphia : G.M. Hopkins & Co., 1873 - Harvard University Library

Week 4, March 1 2014

The past week's progress in 11.016 shed light on nature and urban life's coexistence in the same space. Neither are a solid entity, one does not make room for the other. Both interact plastically and heavily depend on each other. The more I gained insight in how this co-inhabitation in space and time functions, the more I realized how often we neglect it in our design and planning decisions. Very often, we will look upon small efforts towards a better environment as having an impact far too little to make a difference.

But there is particular one quote, from the very beginning of first chapter of The Granite Garden, that struck my attention. After describing efforts by cities all across the world, each with their own problems and difficulties, each solution on its own scale, it read: “Solutions need not be comprehensive, but the understanding of the problem must be.” This one sentence seems to me as one of the best summaries of understanding and improving the interaction of human settlement with surroundings, and, more importantly, its hosting environment. The statement wraps up two important aspects: understanding a situation with its prior mistakes and improvements in decision making, and possible solutions to obtain a better overall quality of life.

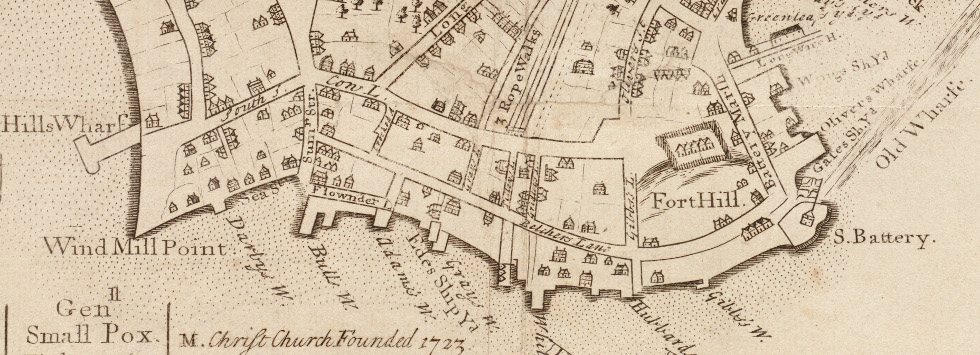

What interests me most about understanding the settlement-nature interaction, is the large range of “scales” its processes can be observed on. Movement of water masses involves whole cities or their neighborhoods, but the presence of certain species growing in cracks of pavement can have as much of an impact on a city's impression on us.

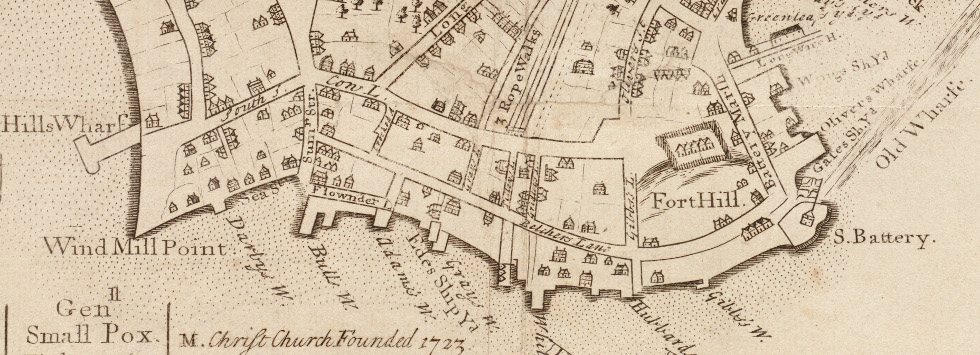

The chapter on Boston: A Natural Environment Transformed then, summarized the reasons of Boston's development, existence, functionality and appearance today. Together with historic maps from Mapping Boston (Krieger, Cobb, Turner) and from the Boston Public Library Collection I can explore how nature shaped and shapes South Station's neighborhood. Interestingly enough, the current Atlantic Avenue seems to be the shore front from 1722, which makes part of the site I chose one of the oldest pieces of land in Boston, and the other part a more recent landfill project. A field trip tomorrow should help discover the areas natural history.

Detail from "The Town of Boston in New England, John Bonner, Published by William Price - Boston Public Library

Week 2, Feb 15 2014

Selecting a site to focus on during the entire semester is challenging. Will its history prove interesting? Are there uses today that are not immediately visible from the surface? Another important aspect is how this site would relate to my personal interests.

It took a while, but I believe I have found “my” snippet of Boston. In fact, I am in it as I am writing this. For the past few years now, I've developed an interest in how infrastructure development, what it does for cities or regions as a whole and how interacts with its direct neighborhood. I was looking for an area with visible, vibrant life, and a major current and/or past transportation function. That's how I ended up here, in South Station. I suspected that this would be an interesting neighborhood to explore, so decided to bike here - even despite the terrible weather – hoping to get a better view on the surroundings than when being dropped off through an underground tunnel. I think I was right: the I-93 is passing right nearby, but recently turned into an enormous stretch of park area, hosting community events like fairs or even the Occupy Boston movement. South Station was and is a major railway terminal, but has not always been which I'm sure will provide some interesting evolutions of the surroundings through time. There is also a stop of Boston's underground subway system, the “T”, providing easy access from within the terminal building to both the orange and red lines. But what makes the area really interesting is everything that happens outside of its transportation function: the direct vicinity also seems to provide homes for people, office buildings and a wide variety of commercial activity. I'm looking forward to coming back here frequently, and discover the rich detail that lies hidden around here.

In class this week, I really enjoyed the Philadelphia case study. I never realized before that the structured road grids and careful city planning as seen in the US started as early as the 1700s. It makes me wonder what city planners back then had in mind for the cities they were designing. Did they envision growth to the extent that “their” downtown would host millions of people after the relatively short time span of a century or two, three? Did they realize that their decisions about where to lay out parks, major avenues and squares would still be defining city life today?

Week 1, Feb 8 2014

The domain of Urban Studies has been one of my secretly kept interests for quite a while now. All too often, you hear people approach exact and social sciences or humanities as if they are entities that live in two divided universes. People develop a passion for one or the other, and often close off to “the other side”, whose followers presumably reside further down the street.

Urban development and all its facets, like infrastructure development, transportation, plazas, neighborhood renovation or migrations is, in my opinion, a beautiful example of where the field of exact sciences intersect with human social interactions. As one analyzes a city, its community, its ups and downs, it is important to look at a variety of factors, ranging from the more statistical (traffic flow, average income, amount of businesses) to the more subtle (remnants of old developments, conversations on the street, the general feel of how things look, …) where the latter are at least equally important, if not more, then the former.

In that sense, I think the Grady Clay reading was eye-opening. It demonstrates how much can be learned from a city or environment, simply by taking the time to open your eyes and analyzing what is physically available, what is visible in everyday life. It brings together more exact analysis employing sources like maps and statistics, with a more subtle approach, employing sources like sights from photographs, or memories of conversations. I especially liked the example of so-called “venturis” because it particularly illustrates this duality. They can be constructed geographically, by physically forcing a flow of people through a certain path, but they are more easily discovered by taking a look at the interactions that take place in a certain area.

Our first lecture then also gave beautiful examples of how what remains today in a city's look or layout reveals important parts of its history – in American cities, but also beyond: in the European cities I am more familiar with. I am excited about the explorations I will be able to make throughout this semester in this class. American city development is very different from what happened to the European cities I have lived in my entire life so far. I'm excited to find out what challenges arise here, how they compare to the discussions I have seen back home, and in what different ways people come up with solutions.

Week 13, May 23 2014

After having presented a summary of my findings as part of this project on Wednesday, now seems an appropriate time to reflect on the project as a whole.

I did not realize at first how the first five presentations that were given on Wednesday related to one another. They all had such a different present state, a different history, a different origin. But during the in class discussion after we had all finished the puzzle started falling together. For the whole semester, I had been looking at South Station: its industry, its history of people moving in and out, towards the neighborhood down the street, the suburb, or another city far away. But I was zooming in on one end of the line: all these newly developed methods of transportation, while certainly reshaping Dewey square, also drastically introduced or changed neighborhoods on their path. The streetcars and subways I saw appearing also appeared in Coolidge corner or Davis Square, but with a very different impact. Functions I saw shifting away appeared on the other end of the line.

I was also surprised to see how similar the Bulfinch Triangle area was in its early days compared to South Station. The railway terminal there brought with it its industry, blacksmiths, liveries and the like much like it did in its southern counterpart. Yet today these two locations in Boston are nothing alike. This change in development can probably be attributed mostly to a single decision from the very end of the twentieth century: centralizing Boston's passenger railway transport in South Station. It keeps impressing me how much influence a single decision can have on an urban environment.

The following sixteen presentations will without doubt reveal more and more broader patterns that were not directly visible from our sites' focus.

Week 12, April 26 2014

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, written in 1961, Jane Jacobs writes: “Of course [city planning] stagnates. It lacks the first requisite for a body of practical and progressing thought: recognition of the kind of problem at issue.” Jacobs refers to city planning being treated with statistical problem solving techniques, without recognizing its organized complexity known from the biological sciences.

I think it is extraordinarily important to reflect on this issue today. Developments of the last two decades, in particular in the field of computational technology, allow for revolutionary, new problem solving techniques to be applied. Because at the basis of every problem in organized complexity lies an easy to model decision making process. What we have failed to realize in the domain of urban planning is that the sum of these lower-level decision making processes is an incredibly complex system that can indeed not be modeled by ordinary probability and statistics, or single mathematical laws.

Yet I strongly believe that we have the technologies for large-scale prediction of the consequences of urban planning decisions at hand. Today, we can run system simulations that simulate thousands of individual-based decision making processes simultaneously. The way they interact as a result of this simulation is not otherwise predictable.

A simple example is that of a traffic system. Traffic, like urban planning as a whole, is a problem of disorganized complexity. It is impossible to predict its behavior based on ordinary probability theory or mathematical laws. Yet it is very straightforward to predict the behavior of an individual on its commute from home to work: he or she will generally follow the fastest route, at a fixed time of day, taking in account the other individuals trying to the same (i.e. avoid traffic jams). Today's technology allows of to run thousands of these single processes (one car) simultaneously. The patterns that emerge reflect what we see in daily life to an incredibly accuracy. Predictions like this were impossible to make two to three decades ago.

Learning to apply large simulation techniques to urban planning is a domain I am personally very interested in. It is definitely the reason I am taking this class (interestingly enough, as the only Electrical Engineering and Computer Science student this year). The Jacobs reading made me realize that the lack of applying readily available knowledge to urban planning has been a problem for decades – and one I can only try to help solve.

Week 10, April 12 2014

Monday's class provided an opportunity for me to briefly present the work I've been doing exploring the history and current situation around South Station and Dewey Square. Most importantly, I got to see the different insights fellow students have on very similar, adjacent or even overlapping sights. The details that meet one's eye are subject to the individual. Therefore every one of us notes possibly similar, but distinct aspects of urban life around our sights. The influence of changes we observed in our own sites obviously extend beyond our arbitrary boundaries, in neighboring sites but possibly even up to miles away. Seeing these changes was exciting.

Wednesday's class gave an interesting insight in the West Philadelphia Landscape Project. I found it interesting to learn how the change of function of a certain site (with settling industry, etc.) changed social structures. The first part of this weeks reading, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History by Dolores Hayden, elaborated on exactly this topic. Her description of “place” puts the observation of the urban landscape into social and general (aesthetic, sensory) perception. I think this is a powerful concept that has been a basis for all the work we did in the context of this class. Hayden's history of a place is a history of those observations that we have been trying to make on our own sites. It is a history of projecting our current observations backwards through time time to understand how citizens back then used and perceived a given space.

I will finish the last part of the Hayden reading by tomorrow, to complete the basis for our last assignment, on Traces and Trends. I am eager to find out what new discoveries I will make around South Station, with the now studies history of the site in the background.

Week 7/8, March 30 2014

This week's main focus has been applying the research we did on our class site in week 6 to our own site. For the Dewey Square and South Station area, the Sanborn Fire Insurances proved extremely resourceful. Accurate maps available from every decade show the site's evolution, its shifting use of transportations and its changes in industries. (large, high-detail maps of the site that I have assembled from sheets of the Sanborn maps are available below)

The break also proved a good time to continue reading Kenneth T. Jackson's Crabgrass Frontier. One aspect of suburbanization that Jackson describes is the duality between transportation and desire for a quieter environment. Is it the developments in transportation technologies that enabled reaching out further into the countryside, or is it the desire of the wealthy to reach out that drove development of more comfortable and affordable transportation?

Exactly this development is extremely applicable to the history of Dewey Square. At first I struggled finding the relevance of a work entirely treating suburbanization, when my site was part of even the earliest settlement in Boston. But then I realized that “moving people” is always a system that goes both ways. For transportation to branch out into the open, the city has to provide a hub where everything connects together. And this is exactly was South Station was and is for Boston.

The original railroad facilities at the site were laid out along the wharves, transporting only cargo. A continuously expanding demand for passenger railways then caused the construction of the south station railway terminal in 1899, now coming from the south in order to connect with people, not goods. By 1989, a streetcar can be found on Atlantic avenue, which was later elevated to make room for the automobile.

Another domain to explore is the site's industrial development. Where in 1867 a high concentration of Blacksmiths can be found around the more southern streats in the area, by 1885 the leather industry is dominant (this explains why this part of Boston is named the “Leather District”).

The Fire Insurance Atlases are not available after 1938. One of my goals for the next few days will be to find resources that cover the last half century. Developments like the Central Artery and Great Dig have strongly shaped Dewey Square, and deserve a good amount of attention.

Week 6, March 15 2014

In class on Wednesday this week, we analyzed the evolution over the past century and a half of a section of our common class site in Cambridge. Our site was what is known today as Technology Square, a recently developed research- and office building area in Cambridge's Kendall Square area, situated between Broadway, Portland St., Main St, and Galileo Galilei Way. In order to understand the evolution of this small plot of land, we looked at a series of 6 maps describing the area as it appeared in 1873 up to today.

The interactive map view below allows the site we analyzed, highlighted and identically positioned on all maps we used, including their sources.

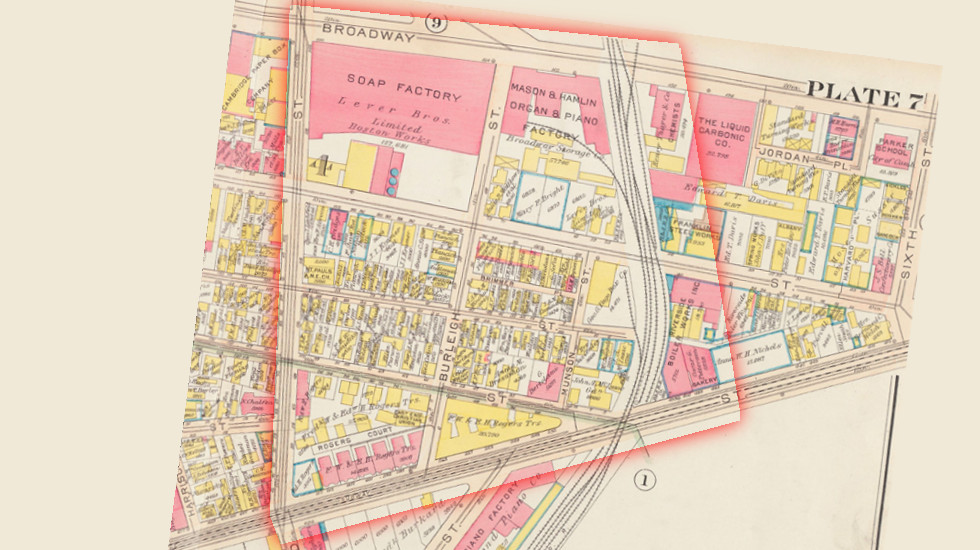

On the oldest map, dating from 1873, the immediately looks significantly different than it does today. The roads are aligned with Broadway, whereas today they are aligned with Main street. Street layouts are one of the most persisting properties of urban areas, which means something unusual must have happened. The land use of the area is also significantly different than it is today. The area between Washington and Harvard Street is a residential area, with isolated single family homes, showing the names of the owners. Some industry can already be found below Broadway, with the railroad extending into the Mason & Hamlin's Organ Factory.

In 1903 we can see that the land between Main St and Washington Street is now developed. The residential area remains, but the industrial area north of Washington street is clearly expanding. Notice how the Lever Brothers Soap Factory has settled in the most north-west block in the site. The railroad now features double tracks, and the branch is extended to the soap factory.

The 1916 map again shows more industrialization of the northern part of the area, and expansion of the railroad running north-south.

Notice how in 1930, the Organ and Piano factory has ended business in this area, and the Lever Brothers Soap Factory has taken over their entire site. Most importantly, a large part of the former residential area has been acquried and demolished by lever brothers. The area around the railroad is now losing its residential function.

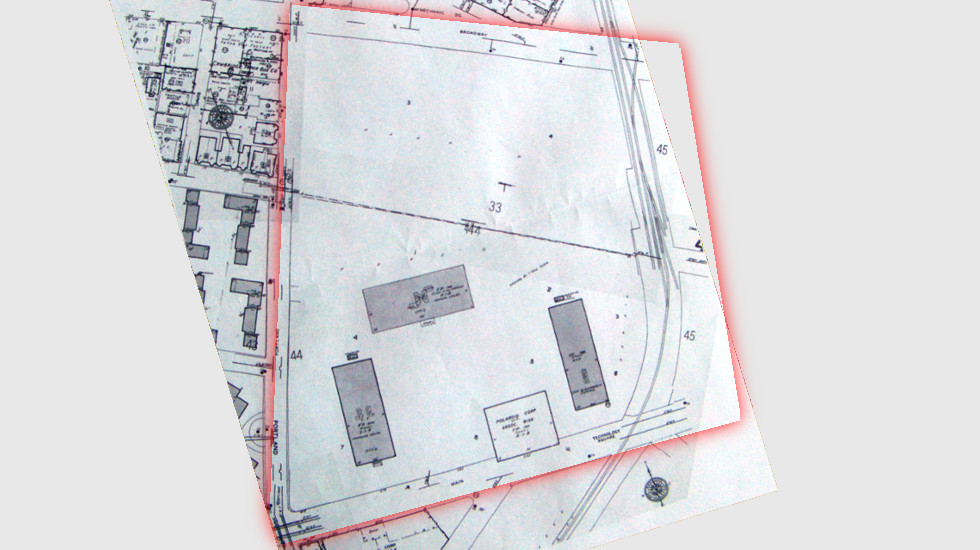

By 1970, the look of the entire area has changed drastically. It turns out that Lever Brothers merged with the Dutch margarine manufacturer Margarine Unie to form one of the biggest soap and food concerns today, Unilever. In an effort to modernize their production facilities, the Cambridge factory was abandoned in the 1950's. By 1970 the site has been completely cleared of buildings and roads, and shows three office buildings: a clue to its new purpose.

Today in 2014 the site has been entirely repopulated, temporarily owned by MIT and real estate companies. It now hosts large office and research buildings.

Feel free to explore more changes using the interactive map view below. The methods we used during Wednesday's class are eye-opening. I hope to be able to do the same thing for the South-Station site I chose soon.

- 2014

- 1970

- 1930

- 1916

- 1903

- 1873

Week 4, March 1 2014

The past week's progress in 11.016 shed light on nature and urban life's coexistence in the same space. Neither are a solid entity, one does not make room for the other. Both interact plastically and heavily depend on each other. The more I gained insight in how this co-inhabitation in space and time functions, the more I realized how often we neglect it in our design and planning decisions. Very often, we will look upon small efforts towards a better environment as having an impact far too little to make a difference.

But there is particular one quote, from the very beginning of first chapter of The Granite Garden, that struck my attention. After describing efforts by cities all across the world, each with their own problems and difficulties, each solution on its own scale, it read: “Solutions need not be comprehensive, but the understanding of the problem must be.” This one sentence seems to me as one of the best summaries of understanding and improving the interaction of human settlement with surroundings, and, more importantly, its hosting environment. The statement wraps up two important aspects: understanding a situation with its prior mistakes and improvements in decision making, and possible solutions to obtain a better overall quality of life.

What interests me most about understanding the settlement-nature interaction, is the large range of “scales” its processes can be observed on. Movement of water masses involves whole cities or their neighborhoods, but the presence of certain species growing in cracks of pavement can have as much of an impact on a city's impression on us.

The chapter on Boston: A Natural Environment Transformed then, summarized the reasons of Boston's development, existence, functionality and appearance today. Together with historic maps from Mapping Boston (Krieger, Cobb, Turner) and from the Boston Public Library Collection I can explore how nature shaped and shapes South Station's neighborhood. Interestingly enough, the current Atlantic Avenue seems to be the shore front from 1722, which makes part of the site I chose one of the oldest pieces of land in Boston, and the other part a more recent landfill project. A field trip tomorrow should help discover the areas natural history.

Detail from "The Town of Boston in New England, John Bonner, Published by William Price - Boston Public Library

Week 2, Feb 15 2014

Selecting a site to focus on during the entire semester is challenging. Will its history prove interesting? Are there uses today that are not immediately visible from the surface? Another important aspect is how this site would relate to my personal interests.

It took a while, but I believe I have found “my” snippet of Boston. In fact, I am in it as I am writing this. For the past few years now, I've developed an interest in how infrastructure development, what it does for cities or regions as a whole and how interacts with its direct neighborhood. I was looking for an area with visible, vibrant life, and a major current and/or past transportation function. That's how I ended up here, in South Station. I suspected that this would be an interesting neighborhood to explore, so decided to bike here - even despite the terrible weather – hoping to get a better view on the surroundings than when being dropped off through an underground tunnel. I think I was right: the I-93 is passing right nearby, but recently turned into an enormous stretch of park area, hosting community events like fairs or even the Occupy Boston movement. South Station was and is a major railway terminal, but has not always been which I'm sure will provide some interesting evolutions of the surroundings through time. There is also a stop of Boston's underground subway system, the “T”, providing easy access from within the terminal building to both the orange and red lines. But what makes the area really interesting is everything that happens outside of its transportation function: the direct vicinity also seems to provide homes for people, office buildings and a wide variety of commercial activity. I'm looking forward to coming back here frequently, and discover the rich detail that lies hidden around here.

In class this week, I really enjoyed the Philadelphia case study. I never realized before that the structured road grids and careful city planning as seen in the US started as early as the 1700s. It makes me wonder what city planners back then had in mind for the cities they were designing. Did they envision growth to the extent that “their” downtown would host millions of people after the relatively short time span of a century or two, three? Did they realize that their decisions about where to lay out parks, major avenues and squares would still be defining city life today?

Week 1, Feb 8 2014

The domain of Urban Studies has been one of my secretly kept interests for quite a while now. All too often, you hear people approach exact and social sciences or humanities as if they are entities that live in two divided universes. People develop a passion for one or the other, and often close off to “the other side”, whose followers presumably reside further down the street.

Urban development and all its facets, like infrastructure development, transportation, plazas, neighborhood renovation or migrations is, in my opinion, a beautiful example of where the field of exact sciences intersect with human social interactions. As one analyzes a city, its community, its ups and downs, it is important to look at a variety of factors, ranging from the more statistical (traffic flow, average income, amount of businesses) to the more subtle (remnants of old developments, conversations on the street, the general feel of how things look, …) where the latter are at least equally important, if not more, then the former.

In that sense, I think the Grady Clay reading was eye-opening. It demonstrates how much can be learned from a city or environment, simply by taking the time to open your eyes and analyzing what is physically available, what is visible in everyday life. It brings together more exact analysis employing sources like maps and statistics, with a more subtle approach, employing sources like sights from photographs, or memories of conversations. I especially liked the example of so-called “venturis” because it particularly illustrates this duality. They can be constructed geographically, by physically forcing a flow of people through a certain path, but they are more easily discovered by taking a look at the interactions that take place in a certain area.

Our first lecture then also gave beautiful examples of how what remains today in a city's look or layout reveals important parts of its history – in American cities, but also beyond: in the European cities I am more familiar with. I am excited about the explorations I will be able to make throughout this semester in this class. American city development is very different from what happened to the European cities I have lived in my entire life so far. I'm excited to find out what challenges arise here, how they compare to the discussions I have seen back home, and in what different ways people come up with solutions.