South Station / Dewey Square

Natural Processes

A walk around Dewey square, about an hour before sunset, reveals its function as New England second largest transportation hub (after Logan Airport). Enormous crowds of people from Boston's financial district and downtown march across the plaza towards the South Station railway terminal and subway stop, in waves carefully synchronized by the traffic lights coordinate all people, cars, trucks and buses that try to use the same space at the same time. Around everyone lies the carefully developed Dewey Square Park, marking the start of the Rose Kennedy Greenway that replaced a giant elevated highway running across the whole Boston downtown area until 2003. The park looks like it is reawakening from its white snow cover finally disappearing after deflecting all incoming sunlight for at least the past month. The trees around the area stand motionless as winter has taken away all their leaves, with piles of excess salt around the small iron grids that are supposed to provide water to their roots. These crowds of people are in a hurry, and have very little time to consider their surroundings. I feel awkward as I stand still amidst them, waiting for small details to catch my eye and camera. Yet these details provide evidence of much larger natural processes, that define how this area was shaped, define what makes this an attractive or unattractive space to be around, define the winds in the commuters' face as they run across towards the entrance of the 1899 South Station building.

Throughout this essay, I will try to structure the interaction between nature and the human and urban environment through a few select observations on the site. It is important to consider at all times that this relationship is “mutual”. There are benefits and problems that nature provides for human settlement and urban development, just as our settlement can provide both habitats and problems for nature. Over time, planners, architects and engineers have attempted to construct an environment in which the overall result of that interaction is optimal for our everyday lives. Some of these attempts are successful, some are not. By not purely evaluating the influence of urbanization on nature, and vice versa, nature's influence on our urban environment, but also the solutions we have already attempted to provide and how they were successful, we can use this information to model our cities to provide more comfort and be more sustainable in the future.

Space

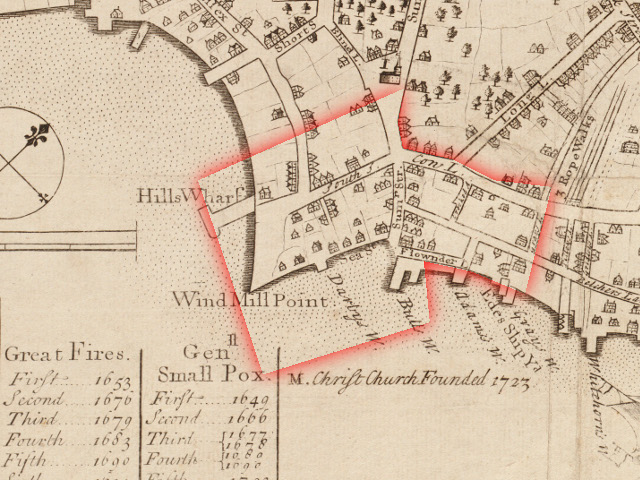

Nature's primary provision to humankind has always been a space to live in. We rely on land to live on, grow our food, and transport most of our goods. For the past two millennia, long distance transportation over water has become increasingly important. The border between these two media of transportation, the seafront, has therefore always been an attractive location to start settlement. This is one of the primary factors that located Boston where it is today. Access to the seafront must have also been the primary reason for the first Bostonians to build in the area of what is now Dewey Square. A 1722 map of the town of Boston, predating even the first landfill operations in Mill Pond from the early 1800s, shows that Summer street provided direct access to the waterfront at that time. What is now known as Purchase Street and Atlantic Avenue already existed on the same map, then labeled Cow- and Belchers lane, respectively. That makes current-day Dewey square one of the rather sparse areas of Boston that have existed for longer than the city itself has. The land east of Atlantic Avenue and south of East street, currently hosting the whole South Station railway terminal, is part of a landfill project from the early 1800s.

Boston Public Library, Leventhal Map Center

Then how does the origin of the land currently supporting the site influence its use today? I had a hard time answering that question through my observations of the site. A lot can be learned from imperfections in our environment, damage to man-made structures that could be a result from instability of the supporting ground, etc. Yet I could find barely any damage to the buildings in the area, whether they were old or rather recent, whether they were constructed with a wealth of resources or clearly constructed at a minimal cost (such as the single abandoned pre-World War II building remaining on Purchase street). But there is as much to be learned from what we don't see as from what we do see. The fact none of the present buildings show structural damage regardless of their age, supports that they are most likely built on original, stable ground. Today, the area hosts some of Boston's tallest highrises, such as One Financial Center and the Federal Reserve of Boston building.

Next to that, we can also recognize the original terrain of the area. Looking down from high street, the land strongly slopes down towards the south east, or what would have originally been the shore front. This is a very common pattern that develops around natural non-rocky shorelines such as that of Boston. The later landfill projects filled up the land up to this original low level and no higher, as transporting filling material is tedious and expensive.

contained nature (see below)

Light

Another day to day luxury nature provides us with is sunlight. A large part of living creatures require light in order to function, and are specifically designed to maximize the amount of sunlight they can catch. Trees artificially placed in an urban environment very clearly show this behavior, they will often lean over away from the walls of buildings near them with the sole purpose of maximizing light infall. The trees along One Financial Center on the extension of Purchase St are a great example of this. The enormous skyscraper placed there as part of the urban environment influences how these trees grow in their surroundings.

Buildings and Trees capturing Sunlight

Buildings and Trees capturing Sunlight

When placing and designing our buildings, we show a similar desire for integrating light. New high rises are often completely covered in glass; we layout interior floor plans to maximize light in living- and workspaces; we like our plazas to appear bright and welcoming. Both nature and mankind competing for light might make a sustainable, comforting combination seem paradoxical. However, it does not need to be. Carefully making use of nature's desire to capture light can improve sidewalks, and promote forms of transportation other than cars. Growing plants in areas where we don't use incoming light, such as roofs of buildings, could potentially reduce air conditioning costs during the hot summer months, and prevent direct access of the cold wind during the winter.

Warmth

Just like the sun radiates light, it also provides all heat for us. The way in which we construct our cities heavily influences how this heat gets absorbed, reflected or dissipated. The Granite Garden clearly explains the phenomenon of the urban heat island on the size of the whole city. Due to the dominating paved and concrete surfaces in a city radiating the heat they absorb a lot more than natural surfaces would, measured temperatures in an urban environment can be up to several degrees Celsius lower than a few kilometers outside of the city, this effect being the strongest in the evening after the sun has set. What it also describes is a local “heat island” effect in an urban surrounding. This effect is clearly present around Dewey square. While the snow in an area is melting, it will reveal the underlying surfaces faster in those areas where the temperatures are higher or that are reached by more direct sunlight. Dewey Square itself, constructed as an open plaza surrounded by five story buildings as well as high rise buildings on all sides, collects incoming sunlight and heats up the contained space. During my last visit, the entire square was cleared of snow, even the grassy areas where no salt was used to melt it away. At the same time, the large open Brigg's field on MIT's Campus in Cambridge, still part of Boston's urban area and as such not significantly less influenced by the Urban Heat Island on the cities' scale, was still completely covered in snow.

During the winter, we experience little disadvantages from this heating effect. In summertime however, it can make the difference between a burning square that the masses desperately avoid or a rich haven where people seek coolness and refreshment. The Granite Garden references a similar phenomenon around Boston's new City Hall dating from 1968. Dewey Square itself however, seems to have been designed to account for this effect in the summer. It is largely covered by a central grass field, which shows much more desirable heat absorption effects than paved surfaces, and trees are planted around the benches to provide some shade. The way in which these trees have been integrated with the paved surface is a little bit more questionable, but we will get back to this later.

The melting snow demonstrates another phenomenon due to incoming direct sunlight along east-west running streets. As the sun never shines upon south facing walls, but is at its highest point when shining upon south facing walls, the snow on that side of the road generally melts faster. This phenomenon also affects the temperature properties of the interior of these buildings, and not only during the winter. It is therefore important to consider these features when assigning functions to different rooms in a building, in order not to needlessly heat up certain rooms while air conditioning others.

One could also consider this property when developing the road layout. For example, it currently is a lot more common in Europe than it is in the United States to construct an asymmetric road layout, where bikes and pedestrians share one side of the road, and cars the other. This would be beneficial for everyone involved. Pedestrians and bikers, who will prefer more sunlight for comfort, could share the south facing side of the road, which can then be enhanced by providing room for trees to grow. These trees would grow better with more sunlight, make the streets overall appearance more appealing and provide a sense of cleanliness. Cars, sharing the north facing side of the road would not be bothered in their visibility by incoming sunlight and would need to use less air conditioning for cooling down the cabin. The overall safety of the situation also improves by reducing the ever-dangerous situations where pedestrians and bikers are in the same space as cars. Bringing cars closer to the wall of the buildings, and narrowing down the appearance of the street by planting trees has also been shown to generally slow down drivers.

Contained Nature

Over the past two decades city governments across the United States and Europe have been starting to realize it is important to re-integrate green into the urban environment. Dewey Square is a great example of this. The site's entire appearance today is defined by carefully placed trees and plants, either from private initiatives, like along the major Financial District buildings, or from city initiatives, such as on the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway, completed in the previous decade. But the way in which these trees are integrated into the concrete environment raises questions. All too often they are thought of as objects that are simply placed – they are not. Trees live, grow, grow roots, and breathe. Trees planted along Summer Street near South Station are cemented in no more than a square foot of soil, covered by a metal grid that is supposed to allow some water to flow through. The rest of the ground surface is mostly paved, either with asphalt for cars or with bricks for pedestrians.

L: Park and Seating area ineffectively placed in a windy passage between tall buildings, the trees soaking up more salt than water

L: Park and Seating area ineffectively placed in a windy passage between tall buildings, the trees soaking up more salt than water/ R: Integration of bushes and trees next to One Finacial Center, leaning towards the right to seek light.

As much as this is is an improvement over what used to be here, we need to consider if this situation is ideal. Piles of excess salt used for removing snow off the surface are left right around the tree's water intake covers. This salt will soon, with the next rainfall or melting snow, permeate into the little soil these trees have and unbalance their water absorption (in natural environments that are salty due to inflow of seawater have entirely different vegetations, with species specifically adapted to maintain appropriate water levels at all times). If these trees survive at all, we can never expect them to grow to their full size and provide a wealth of shade and coolness as they would when they had the opportunity to grow in a free environment, as is proven by the fact that they have been here for over a decade and haven't seen much significant growth.

Next to these plants' chances of survival or growth, it is important to consider the effectiveness of the placement of green into our street settings. Climbing up to the top of a parking garage on Lincoln street gives a good overview of the integration of green in the major traffic node that is the intersection with Essex Street and the extension of purchase Street (officially named John F. Fitzgerald Surface Road). A desolate island with concrete boundaries and a few tries on it is locked in between a parking lot, and two of the busiest streets in the area. All good intentions aside, this triangle of “contained nature” within walls of pollutants and asphalt serves no purpose. Given the sparse light they see, these trees will not freshen the air, nor do they provide a safe location for bystanders to relax: the location is noisy and permanently polluted by all the vehicles accelerating at the busy intersection right next to it. Integration of nature into the urban environment is important, but must be thought through properly. Is this optimal use of the available space? Can we group together certain uses of the space to optimize how they interact with the users (i.e. pedestrians, bikers, drivers)?

L: Isolated triangle with a few tries, locked in between asphalt and concrete / R: Overview of aritifically added nature in surroundings (both taken from top of a parking garage), dominated by traffic chaos

L: Isolated triangle with a few tries, locked in between asphalt and concrete / R: Overview of aritifically added nature in surroundings (both taken from top of a parking garage), dominated by traffic chaos

Dewey Square is in general one of Boston's more recently renovated and well maintained areas. It is also one of the areas where a lot of attention as been given to improve the appeareance by integrating green space into the environment. When seen in retrospect, it also makes very intelligent use of the original geography: the land that was originally part of the Shawmut peninsula on which Boston was founded is used wisely for structures that require maximal stability, such as skyscrapers. The area that has been filled in artificially is currently used for Boston's biggest railway terminal: a structure that requires a large plot of flat land (a feature always provided by landfill). The water flowing onto Dewey Square from High Street is collected nicely into the many sewer entrances integrated into the square's pavement and by the large grass field. But much room for improvement remains. Large crowds of people try to cross the constantly congested streets in complete chaos, through winds funneled together by the tall buildings, in sunlight falling in from every possible angle. A lot of the artificially added plants look out of place and desolate, and are placed in sub-optimal conditions. Integration of nature into our urban environments, and thoughtfulness about natural process in city design is an ongoing process: we've come a long way since a few decades ago, and have a lot of improvements to make in our future.

Bibliography

Anne Whiston Spirn, The granite garden : urban nature and human design. New York: Basic Books, 1984.Alex Krieger, David Cobb, Norman B. Leventhal, Amy Turner, Mapping Boston, Boston: The MIT Press, 2001.