|

|||||||||||||

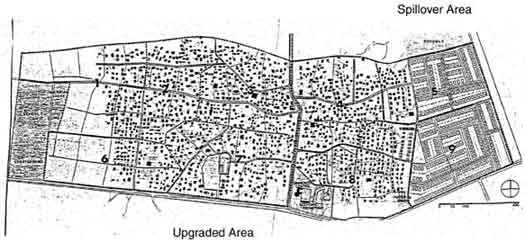

Kalingalinga Integrated Upgrading ProjectExample of: • Comprehensive Integrated Project |

|||||||||||||

|

Lusaka, Zambia |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Summary

|

Kalingalinga was a joint project of the Lusaka Urban District Council (LUDC) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft f|r Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). It was seen as a comprehensive project integrating physical, social as well as economic improvement efforts. The project was first conceived in 1979, launched in 1980, and completed in 1987, with follow-up support continuing through till 1992. At initiation, the area contained 13,000 people in 1,460 houses. 2/3 of the project costs came from GTZ grants. The goal was to involve people in the decision making, planning, and execution process of upgrading, and to integrate social and economic improvement along with upgrading houses and infrastructure. To avoid the problem of special implementation units, the project was developed as part of a normal 'line-agency' function and no special project implementation unit was envisioned.

|

||||||||||||

|

For further information:

|

Kalingalinga: Community on the Move, GTZ report, No. 175, Eschborn, 1987.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Background

|

A priest acted as catalyst to initiate donor efforts for upgrading of this centrally located but neglected transitional community. It had been omitted from the previous LUDC/World Bank upgrading program which had covered much of the city. LUDC and GTZ staff with newly established community representative group agreed on a plan of action, after intensive planning meetings held to familiarize officials and staff in goals and issues in the project. The community representative body and the housing section in the LUDC were charged with implementing the project, and occasional expatriate inputs provided technical assistance and training. A post mortem evaluation was commissioned in 1994 to assess results and draw lessons.

|

||||||||||||

|

Components

|

Included was the provision of school, clinic, markets and community center; installation of water standpipes to groups of families; roads, street lighting; house improvement loans through a community revolving fund; core house material loan program through community revolving fund; promotion of economic activities and income generation through micro-loans; experimentation with lower cost construction materials and techniques, alternative sanitation methods; and secure title to the land. The project including realignment of dwellings and lots to lower densities and to allow for widening streets. Building material loans were offered first to families who had to be relocated into an adjacent overspill area .

|

||||||||||||

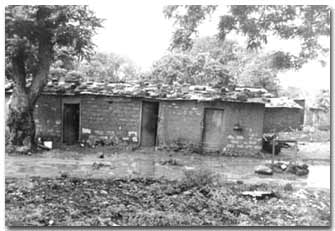

Kalingalinga Project: Houses throughout the area were |

|||||||||||||

|

Lessons:

What worked and why? |

|

||||||||||||

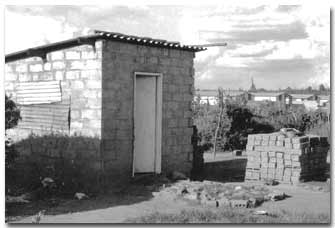

Kalingalinga Project: Materials loans were given for single room |

|||||||||||||

|

What didn't work and why?

|

Alternative soil-cement block manufactured through cooperatives proved to be non-competitive and not popular. First choice was cement block since they provided a sense of permanence and contrasted with traditional rural construction. Their use also allowed higher rents. Double-pit composting latrines proved to be culturally unacceptable and too expensive. |

||||||||||||

Kalingalinga Project: Core houses rapidly expanded |

|||||||||||||

|

Tips:

|

|

||||||||||||

|

To Learn More:

|

Kalingalinga: Community on the Move, GTZ report, No. 175, Eschborn, 1987.

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||