Evolution and Achievements

MS. ZIPPERER:

What has been achieved in Ghana so far?

MR. BANES:

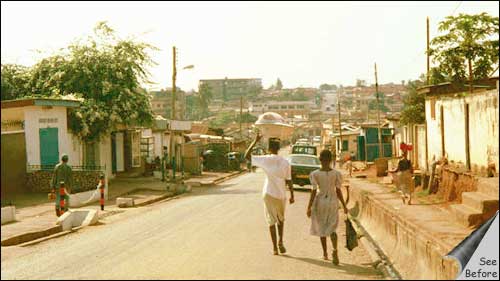

In total, this program affects half a million people over almost 1,000 hectares in 12 communities, in 5 cities. It is not national by any means, but it has been a good start and was doubled up with the Urban Environmental Sanitation Project (UESP) where we upgraded seven communities, over a quarter million people in 500 hectares.

MR. GATTONI:

Comparing the upgrading efforts in Indonesia with the upgrading program in Ghana, it seems that the fundamental thing in Indonesia was the built-in capacity of the so called KIP unit, that was doing a lot of things in-house, that knew what it was doing and did them without much complication. In Ghana, we have a series of projects that have set up some sort of mechanism that relies heavily on subcontracting doing things in various cities in a decentralized way.

What do you conclude about Ghana - using what it has done under these projects that you have been talking about - if we would expect them to go from half a million to 6 or 8 million in the next 10 years? Do you think there is enough capacity to be able to take that on in the next project?

MR. BANES:

I think going up to scale at this moment would be difficult in Ghana, but the pace of upgrading initiatives which have developed in this country has been right. This process started 10, 15 years ago and there was very little knowledge of what could be achieved with the multisectoral, integrated approach to basic infrastructure provision in these areas. Probably the Bank and/or other donors were saying this is what has been done in the KIP. So they said, yes, we'll give it a try, and the project unit for the first Bank project overall, the ADRP, staffed it up with a lot of young, bright guys out of the University of Science and Technology, among them architects, planners and engineers. The Bank teams worked with them, and they cut their teeth on the pilot project, which was a small, 30 hectares project.

15 years ago, the Ministry of Works and Housing was very weak. Ghana was then a centralist country. Everything was directed top-down from the Ministry of Works and Housing. So the Bank latched its project unit, the Technical Services Center, onto the Ministry of Works and Housing, and it was driven technically. It probably wasn't the ideal way to go, but I think it was the only way to go at that time, because frankly, at the ministry level, government was totally incompetent, technically.

Ghana started to be decentralized a few years ago. Decentralization does not necessarily mean weakening the central government. The latter does not have to be large, but at least it has to know what it is doing. Maybe the Ministry of Local Government in Ghana is getting too big, and maybe there is a bit of empire-building, but I think it is now technically competent. It has been able to become more competent because of the contract staff in the ministry, the local government support unit, which is the central agency driving all the Bank projects and other donors projects involving the assemblies.

It is a development process for the communities to learn of these new initiatives. Now the consulting business is beginning to accept that there is a different way of doing things rather than a very traditional, conventional engineering approach using entrenched standards. The contractors have learned, and I think the units and government have learned, too.

MR. GATTONI:

So there is a capturing of knowledge and learning from it.

Maybe another interesting question is how do you make sure that knowledge base is not lost, or in fact perhaps is enhanced; and then, secondly, how do you make sure that institutionally, this gets passed on from one project to the next?

It seems that a sequence of projects, like we saw with KIP and the Ghana project, gives you some continuity and therefore helps in that knowledge-gaining process. But maybe there is a need to do more about recording the experiences as they go along.

MR. BANES:

Within the Ghana civil service and the local government service, there is some continuity which is surprising, given the woeful remuneration they get. But I think the continuity with regard to the project unit is that they have had perks. The usual way they are kept on is they all get a new vehicle; every new Bank project means a new vehicle. And now there is a move to take people on contract. Of course, that upsets the system a bit.

We have been tinkering around with civil service and local government reform for a long time, but if we haven't found a solution so far. For the moment we continue doing other things like contracting staff as consultants or giving them perks so that they accept the poor salary situation.

But has there been any training in upgrading? In recent years, I went on missions where we weren't talking about upgrading at all. There was nobody who knew what upgrading was, except myself, being an old hand and having done it before. That is a bit sad. When I had my first interface with the Bank in 1975, there were two things the Bank did: it lent money for programs in the urban sector, the sector I was involved with, and it had a lot of specialists who helped agencies to develop their programs. That second thing seemed to me to be lost over the years. I kept hearing that the Bank was a bank and not in the technical assistance business. But I think the Bank has to be more than just a bank.

Anyway, that was another way for the Bank to get over the upgrading message in Ghana, because over the years, they had sent a couple of guys who had done some upgrading.

MR. GATTONI:

And knew what it was about.

MR. BANES:

Yes. And I think that is very much potluck for the country. Nigeria had the same opportunity, but they didn't show any political commitment. In Ghana, although there was skepticism at the beginning, now people have realized that the project has benefits. Once again, political commitment is crucial. But getting the message over was something that I think the Bank should have done more in these years and has been lost.

MR. GATTONI:

Yes. It may be necessary to do a lot more now to catch up, especially when we are talking about doing big-scale things in places that have not had the experience that Ghana has had. We are going to try this in places that are just starting out, and it's going to be very tough.

MR. BANES:

Yes. My experience in Ghana is that you only have to get together with the local government. There are lots of bright guys working in these project support teams that were set up under UESP. If you sit down with them they will argue at the beginning and say, "these are inferior standards". But when you explain everything to them, they will begin to realize, "fine, let's stick with our conventional standards, let's stick with the design guide here, okay, and let's have a look at what it is going to cost.

Key elements of sustainable upgrading: Political Commitment

MR. CHAVEZ:

If upgrading projects can not be implemented or are not successful, what do you think is the main ingredient lacking?

MR. BANES:

Well, to begin with, political commitment.

MR. CHAVEZ:

Do you have any thoughts on how you can spark political commitment?

MR. BANES:

That's a good question. I think the governments have to see that it works on other places. In the case of Nigeria, for example, we made that offer, that they should go and look. But the problem there, Roberto, was that we, together with officials, had selected the worst area, a horrific area, called Ajegunle. We were doing some main drainage there. I remember, George agreed to fund me to stay for a couple of weeks to work and we set up a team. It was in the middle of the rainy season and we spent two weeks slogging through the mud. We got some old maps and the old felt-tip pen planning.

MR. CHAVEZ:

Did you have access to any aerial photography?

MR. BANES:

Well, we had this map, we blew up from aerial photographs. And we tramped through this area, through the mud, in the rain, planning this thing out. It was a big area. There must have been at least 5,000 people. Finally, we had a little scheme. But when we presented it to the state government, they rejected it.

MR. CHAVEZ:

That was really a missed opportunity, wasn't it?

MR. BANES:

Yes. We have wasted 15 years. Fortunately, upgrading is starting now.

R. CHAVEZ:

The lessons that you have drawn are really very interesting. As you said, political will is of crucial importance for successful upgrading. Other key elements are the use of local resources, both human resources and material resources, as well as the need to adapt our own support to the way the local governments do business rather than trying to enforce our rules. And lastly, the buying of the community. If the community starts to see improvements, others see them, too, and then a chain reaction starts.

Key elements of sustainable upgrading: Simplicity

MR. GATTONI:

The KIP program in Indonesia was very successful because it had a simple, locally grown and pragmatic approach to bringing basic services quickly to a huge number of people. Our evolution of work in upgrading at the Bank has made it more and more complex, or more cumbersome in a way.

During his career, Chris has continued to apply that same concept of simplicity in upgrading, and what Chris has done in Africa has been very appropriate for Africa. It has been to take that simple approach to getting just the basic appropriate standards. I have noticed throughout the years of Chris' work that he has an excellent way of making sure that what you do in a project are the most simple things. And these have the biggest impact. When a project got too fancy, we have bogged down. I'd like Chris to explain us this approach of simplicity, so that we can learn from it.

MR. BANES:

To keep a project simple, upgrading should first of all concentrate on the provision of basic services. This package of basic services includes the building and paving of a main access route to a standard which is sufficient. Usually, the main route is a two-lane road, with open side drains which often double up as the sullage drain. Sullage is gray water, bath water, washing water, water that is used in the kitchen, but that goes to the storm drains. Then the different roads, such as the area road, the community and the kampung road, as well as the drainage network, have to be linked to the primary distributor to the area. It has to be ensured that there is some primary infrastructure with which the secondary infrastructure can be served.

Ensuring water supply means the installation of a basic reticulation system which would serve standpipes, and depending on where the community is in its development, you would design it such that there could be some individual house connections, should they be demanded.

Sanitation is usually on-plot. There are some cities in some countries where sewerage is the norm, but normally, it is an on-plot sanitation solution or a communal sanitation solution. There are various options.

To keep a project simple, we tend to do basic planning and engineering work for the infrastructure. This also includes simple designs. We avoid doing a different design for every community. Instead we have design and construction standards, such as standard road cross-sections for different widths, standard drain sections, standard public tap facilities, standard communal toilet blocks, as well as standard individual pit latrines. In KIP, we also had planning standards. Having looked at what could be afforded and what could be achieved in one area, we used to say you can't have more than 100 meters of road of this size within that hectare on a per-hectare basis; you can only have so much foot path; in Ghana, one public tap per 5 hectares; so many street lights per kilometer of road, etc. And you have to be fairly rigid about those standards and to figure out what it will cost to do that.

Once you start with this menu, the cost target, the basic standards etc., you can keep the program fairly simple and be able to move forward quickly. Whereas if you start with the clean sheet of paper, go into the community and start from scratch, it's a long, long process in my experience.

Key elements of sustainable upgrading: Community Participation

MR. BANES:

I mentioned community participation. This is a very important element, but it has to be balanced so that you can move ahead quickly. However, the community should not be as strongly involved so that you get such a proliferation of different requirements which would make the planning and design of a program impossible. The biggest problem we had by involving the community, e.g. in Ghana, was that the community expected that improvements will start already within two or three months. But government procedures don't work like that, and when you overlay Bank procedures on top of those, you can't improve anything very quickly.

So whatever you do, don't involve the community too early in the process. It is not an easy thing to find out when to begin to involve the community. If you involve them already when you first start looking at building a database, and you don't even know whether it is that community that is going to be funded under a given project, then it is very unfair to involve it and waste it's time and effort and raise it's expectations knowing it may take five years until you can do something.

In my experience, you have to start off with something on the table. If you start with a bare table, just saying: "Guys, what do you want to do?", they will perhaps tell you that they want a school. But then you have to explain that the Bank is funding this project, and that we can't build a school, because that would have to be financed with another pot of money through another project. So, right at the beginning you have to know what you can achieve and how you can achieve it.

MS. ZIPPERER:

That means that you have to prepare the community before it can participate in the upgrading process. Was it easier to involve it in Indonesia than in Ghana?

MR. BANES:

In Ghana, in the first generation of projects, there was no structured community involvement. Of course, if you walk into one of these communities there is a crowd around you straightaway. The same happens to the local consultants and the local government officials if they go there. As soon as they put up their survey instruments the crowd is around. The people ask you questions, and you have to answer them or you don't get out of the community.

Now, this is not the sort of structured involvement that the social scientist would say is required, but there is always some community involvement. You can't do anything in these communities unless there is a certain involvement. Actually, the contractors who implement the project have most contact with the community. There are the chiefs and the sub-chiefs of the community coming out and saying, "You have to do this, because you are in trouble if you don't do this or that" in this area. So there is this pressure. The contractors know that they have to keep the community leaders sweet, because otherwise, his machinery and his materials would disappear overnight. So there is a lot of involvement between the contractor and the community.

You have to find a contractor who knows how to deal with the people, then you won't have any difficulties. I have been to sites with lots of problems. But you have only to talk to the contractor to realize why he is having problems. If everything you say he doesn't like, you know he is going to have the same communication problems and discussions with the community. You can develop a feeling for a contractor whether he is on the ball, and I think these guys in Ghana were generally pretty good.

MS. ZIPPERER:

What about the NGOs?

MR BANES:

The NGOs are doing a great job, but they work too slowly. In Ghana, for instance, they have been five years tinkering around with a little community sanitation component. I think these slum areas are growing faster than NGOs are able to deal with them with that approach, so the community involvement has to be balanced. At the same time we have to tell them "Guys, you have to come to closure on this. We have to move forward. You are complaining that you've been waiting for a long time. You have to make these decisions, and you have to stick to them, and this is the way we're going to do it because this is the quickest way of doing it."

Challenges: Mapping and Tenure

MR. GATTONI:

Chris, let's talk a bit about a couple of critical aspects of upgrading that we haven't yet touched upon. One of the things that we see is that the cities have grown very fast in a very disorderly fashion. There is little information and data for planning how you do upgrading. I wonder what you found useful to keep in mind when you are starting to do the physical planning of these areas. Sometimes, there are not even street names or addresses; how do you know who lives where, and what happens when people move in, because they know there is an upgrading project coming on?

The second question concerns tenure. There is much debate. KIP has the notoriety that it didn't deal very much with tenure. In Africa, it is very hard to deal with land tenure issues. I'd like you to tell us a bit about your experience and your thoughts regarding tenure.

Talk a little bit about those two aspects: the preparing for planning and the question of land.

MR. BANES:

Well, concerning the preparing for planning, this often causes delay at the start. I mean, people know where the communities broadly are, and on a large-scale plan, you can see where these areas are. But there is no precise plan. So then you look for aerial photographs, and they are 20 years old. That is really a constraint which slows things down. In Ghana, in the cities that we are dealing with, we try to get a mapping exercise done. Often it is a flying exercise which is not really the best way to do it. To fly the whole country or a whole region is very expensive, and the task manager will say, "No, we can't afford to do that. We can only do it for our project".

So to get a national mapping project should be one of these things that is almost a forerunner to get there, and then establishing the wherewithal, the mechanisms to keep things updated.

That is a problem. On the plus side, of course, labor is fairly cheap, so it is amazing that field survey teams get in there and can knock out a map that is good enough for engineering design. It is not a cadastral map, but it's good enough for planning and engineering design, and they can do it fairly quickly.

Mapping is a constraint, and that is something that I think we should be addressing in parallel programs.

MR. GATTONI:

This is for large-scale programs.

MR. BANES: