|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

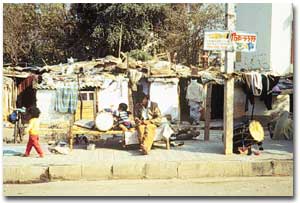

Three general approaches can be taken when upgrading: upgrade in place, clear and redevelop, and clear and relocate. Considerations in deciding include the impact of highrises and the poor when redeveloping or relocating, the notion of ‘temporary’ upgrading in particularly problematic areas, and demolition.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

A Story |

||||||||||||

High Rises and the Poor |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Vitas Housing in Tondo: What happens when poor people who live on the ground, are 'upgraded' into flats that are up in the air? There are some obvious benefits in "going up," since more people can be packed into less land. But it's expensive, hard to maintain and the complex web of connections which knit poor communities together do not always survive the transition from street to sky. The National Housing Authority's enormous Vitas Housing Project was built in Tondo, Manila, in the 1980s to resettle families displaced by the Port Authority's new container terminal. Ten of the project's 27 buildings were allocated for socialized housing while the rest were sold on the open market. The brand-new, engineer-designed, pink-painted buildings were inaugurated in 1990, and marked a revival of NHA's medium-rise housing program. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Vitas Housing Project, Philippines. |

||||||||||||

|

Contact between neighbors on different floors is due mostly to quarrels. In one instance, a woman hacked down her upstairs neighbor's door with a jungle bodo when there was a leak. Unoccupied buildings elsewhere have been invaded by squatters and social divisions throughout the project have made the entire area into a war-zone. Drugs, crime and violence are getting worse, kids are kept locked inside their small units for safety. Only 33% of the residents belong to one of the 18 residents organizations which have formed in different buildings. There is no project-wide community association.

|

||||||||||||

Vitas Housing Project, Philippines. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

*Urban Poor Associates can be reached by contacting: Urban Poor Associates, Ananeza Aban, Ana Marie Dizon, 80-A, Malakas Street, Barangay Pinyahan, Diliman, Quezon City 1116, Philippines, Telephone: (632) 426 4119/926 6755 Fax: (632)426 4118, E-mail: emc321@wtouch.net. |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

Temporary Upgrading? |

||||||||||||

|

The Newspaper Headline:

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Is it conceivable that upgrading can be carried out on a temporary basis? Can minor improvements be prudent even when the location is clearly inappropriate and even unsafe?

|

||||||||||||

The Story

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

Is Demolition the Way to Go? |

||||||||||||

Excerpted from: |

||||||||||||

|

Slum Clearance and Public Housing For nearly 40 years, developing countries sought to solve the problems of poverty and housing deficiencies by removing the poor from slum neighbourhoods and rehousing them in more durable shelter. The failure of these policies led many developing countries during the 1960s and 1970s to try massive public housing construction. The problems of the poor were defined primarily by the condition of their housing, and the solution was to construct public units with relatively low rents. Again, neither services nor employment opportunities were usually provided, and the results were equally disappointing. The cost of public housing construction was high and rentals were expensive. As a result, these policies benefited middle-income rather than the poorest families. Most slum dwellers were merely pushed from cleared sites to other parts of the city. In Madras, India, for example, slums containing more than 58,000 families were cleared between the early 1950s and the mid-1970s, replacing their shanties with public housing tenements. As in many other cities that attempted to solve shelter problems through public housing programmes, the costs of construction in Madras were much higher than expected and the acquisition of private land was seriously delayed by litigation. In the meantime, the slum population continued to grow rapidly. As a result, in the mid-1970s the Slum Clearance Board restricted such activities to floodprone areas and to those places in the city where land would be taken for highways or other public purposes (Seguchi, 1985). Countries with rapidly growing economies were no more successful with slum removal and public housing for meeting the needs of the poorest groups than countries with sluggish economic growth. The inability of slum clearance, relocation, and public housing policies alone to deal effectively with the problems of slum dwellers or to provide other services needed by growing numbers of poor households in urban settlements became clear by the early 1970s. Among the most serious problems with these policies are that they are extremely costly for national governments because of the high level of compensation paid to owners of demolished properties; they create serious problems of social displacement and disruption for the residents of slum and squatter settlements; they are often delayed by social and political pressures exerted by slum residents who resist forced removal from their homes; and, they impose high transport costs on families who are relocated far from their workplaces in the centre of the city. Moreover, the policies do not alleviate the housing problems of the poor and indeed, exacerbate them in many countries. The poor cannot afford much of the public housing that replaces slum dwellings and, thus, the destruction of slum communities often reduces the stock of low-income housing and worsens overcrowding in low-rent units. Often slum clearance in one part of the city simply increases overcrowding in other slum communities (World Bank, 1980; Kulaba, 1982). Although government-sponsored low-cost housing for the poor still plays an important role in shelter provision policies in developing countries, experience suggests that by itself it is too costly and limited in scope to meet the shelter needs of the poorest households. If public housing policies are to operate more effectively, municipalities must be able to expand their general revenue bases, enact new tax provisions that generate special revenues earmarked for public housing construction and maintenance, and increase their assets by borrowing. This will require the creation or expansion of municipal bond markets for public housing. Most governments have depended on purchasing property from private owners or on eminent domain to acquire land for public housing projects. However, if the costs of public housing construction are to be reduced, governments will have to turn to other land acquisition options, including land readjustment and acquisition in advance of need. In developing countries, public policies will have to be combined with other options for shelter provision to reduce shelter deficiencies. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

A Story: |

||||||||||||

Is Demolition Prolonging Housing Problems? |

||||||||||||

Excerpt from: |

||||||||||||

|

The following is a real illustration of how demolition of “problem areas” really does not solve any problems from the long-term municipal standpoint. It creates a burden on the city and hardship for the poor. The Mahakali story is a classic example of urban development that doesn’t solve problems but only postpones them, hoping they’ll go away. The 226 houses in the Mahakali pavement settlement were part of a larger slum that was cleared years ago, to make room for a new arterial road in Worli. Back then, most of the families didn’t qualify for resettlement, and those who did were unable to survive out at Malvani, where the city had dumped them. So many ended up on the pavements back in Mahakali. When they began building a Mahila Milan collective with help from Byculla pavement dwellers, they knew rough times were ahead. A few years later, the Mahakali settlement found itself again in the path of urban improvement, this time for a road-widening. Despite urgent negotiations, the municipal demolition trucks finally came and hundreds of huts were destroyed. The Mahakai community remained steadfast, throughout, and is now planning for its eventual resettlement, which the new SRA policy entitles them to (Citywatch: India 3). |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||