|

|

Getting Started: Project Definition

What About Preventive Measures?

|

Upgrading’ is essentially a reactive approach. What could be done proactively to mitigate the need for difficult and costly upgrading?

Spatial Planning Grids for Directing Growth may be used at the city scale to provide a structure for growth. A Growth Pole approach offers a more active spatial, administrative and financial planning technique for governments to bring vacant land into residential use of the low income. Some examples of proactive intervention strategies point out cities where efforts have worked.

|

|

Spatial Planning Grids for Directing Growth

|

Resource:

Large Orderly Frameworks (LOF) for Rapidly Expanding Urban Areas in the Third World. Goethert, Reinhard. 1986. CIB Proceedings, Washington, D.C.

|

|

The purpose of a large planning grid is to guide and channel urbanization to forestall ad hoc squatting which make future upgrading more costly and difficult. The grid is in response to:

- Need to accommodate new growth

- Inability to control squatting

- Limited institutional capacity

- Need for large-scale efforts

- Need for speed.

Large planning grids are also called guided land development and primary infrastructure networks. Both are variations on the basic concept.

There are several advantages:

- It provides an immediate action that can address growth issues without lengthy study or detailed preplanning.

- It is proactive and allows some degree of directing growth.

- It focuses efforts on the minimum necessary and does not overburden municipalities. It is premised on the question: “what is the minimum that a municipality must do”?

- It allows more predictability of major infrastructure investment.

- It provides flexibility in land use, since only the structure is fixed. It is responsive to market demands.

- It provides a ‘holding action’ to give time for municipalities to develop their institutional capacity.

|

|

Models for rapid structured settlement

Organized squatter invasions in Peru and other Latin American cities in the 60s provide success stories in orderly minimally controlled development. “Pueblo Jovenes in Peru and the “chalk” approach in Chile (boundaries laid out in lime) are two examples of institutional attempts to duplicate squatting. The ‘Law of the Indies’ - the rules given to early Spanish colonizers for structuring cities - was particularly successful throughout Latin America. In the United States, the original land surveys of 1784 provided the framework for settlement throughout the continent except for the original coastal states. This National Land Grid organized large agriculture holdings, townships and provided a subdivision structure down to individual blocks. Note any city plan in the west, for example Chicago, San Francisco and every city in-between. More recent Planned Unit Developments in the United States conveyed blanket approval for a development within a larger area and prescribed rules for the interior . Emergency housing and refugee settlements are other models for review. Agriculture land holdings - for example in Egypt - are perhaps the ideal of ‘no-control’ controlled development. |

Lima, Peru. Organized squatter invasions anticipated future legalization and upgrading.

|

|

San Juan, Puerto Rico. Most of the Latin American cities followed the ‘Law of the Indies’ guidelines. |

|

|

| |

|

How is it planned

The grid corresponds to major arterial roads. It is an approach premised on attracting development, and not on restricting development. The emphasis is on a physical response. Characteristics include:

- It must be flexible and relate to the topography and thus drainage.

- It must mesh with existing links to the city to anticipated growth areas.

To minimize the risks of misjudging growth, improvements within the planning grid should be undertaken only gradually, in step with the progress of urbanization.

An example of stages:

1 - Lay out and stake the rights-of-way.

2 - Build a simple earth roadway with drainage ditches.

3 - Reinforce the roads that carry the most traffic and improve drainage and intersections.

4 - Provide services as demand warrants and can be paid for.

There are two levels to a planning grid:

1 - A large organizing frame. This corresponds to the municipality’s interest of knowing where development will take place: a largely physical component. Areas for future community facilities must be designed. Lack of space for schools and open areas is a key problem in squatter settlements. The interval of the structuring grid ranges from 400-500 meters to 1000 meters. Smaller grids relate better to walking distances to the major roads.

2 - An infill process. This is of interest to settlers: a process orientation. How will the land be settled? Can the typical squatter process be effective or even function in this semi-structured context? What kind of guide can be given to settlers so future titling and installation of infrastructure can proceed rapidly and cost effectively? Entrepreneurs and settlers, as well as cooperative groups, could participate in the settlement process. Technical assistance and financial incentives may be offered to assure an orderly pattern.

How is it paid for?

It is the reverse of the traditional services-first-than-housing:

1 - Settlers move into area and stake out claim to lot.

2 - Houses are built buy settlers.

3 - Infrastructure is installed.

4 - Charges are levied.

Some cautions and fears

1 - Knowing the location of future roads offers opportunities for land speculation.

2 - To what extent would the preplanning encourage sprawl?

3 - Would it be difficult to accommodate existing structures?

4 - Is there a risk of internal squalor? How do you direct settlers into a orderly settlement pattern with minimum control?

5 - Is it necessary to control the size of lot claimed by settlers? How could this be done? |

Cairo, Egypt. The irrigation pattern is an example of an ‘autonomous’ large scale land development process. Main irrigation canals become main streets, and gravity-fed sewage networks. Agriculture properties become secondary streets and property lines.

|

|

The Growth Pole System

|

The Growth Pole System: An Alternative Program for Low-Income Housing in Colombia, South America. Kessler, Earl, and Edward Stanley Popko. Unpublished MIT Thesis. Cambridge, June 1971. 225 pages.

|

|

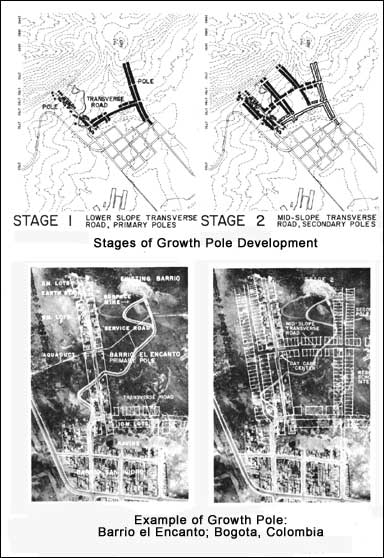

The ‘growth pole system’ provides an overall subdivision plan with a minimum set of services. Housing is then constructed by settlers through self-housing processes. The ‘growth pole system’ does not provide housing, but does provide vacant lots in a pre-established subdivision plan. It insures legal tenure of homebuilders by settling lots with titles. By providing an overall subdivision plan that considers infrastructure, open space and public facilities, the home builder is assured that his efforts to build a house will not be frustrated by a lack of overall barrio planning or legal security.

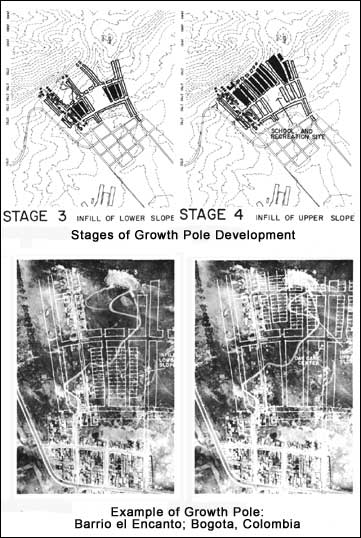

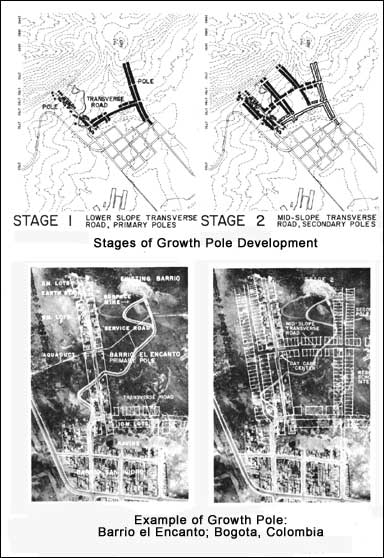

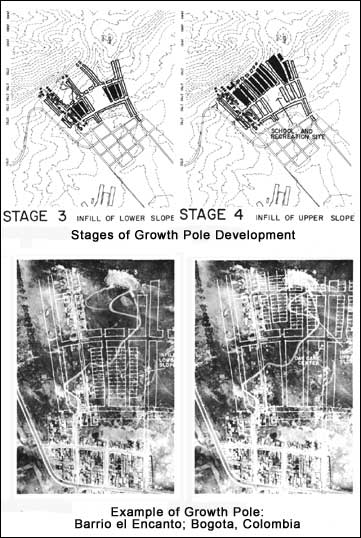

In its simplest form the ‘growth pole system’ controls the sequence and pattern by which land is settled for housing. There are two physical elements: the first is an overall subdivision plan for a minimum 1000 families, which includes lots, street layouts, reserved and for schools, parks and other land uses. The second are selected areas that receive full and complete development, excluding the building of. These fully developed areas are designated as ‘poles’ and contain full water, sewer, and electrical services, as well as street paving. The function of the poles is to attract homebuyers to specific sites. These poles cluster and concentrate efforts of self-helpers in beginning their homes. The poles also provide the points to which services are extended into newly developed areas.

The use of poles can promote home building without the huge expenditures of capital and time that total ‘site and services’ approaches require. From the potential homebuilder, it offers the advantage of acquiring legal title to a lot that is part of larger overall development plan. He is assured that provisions have been made for necessary utilities.

The growth pole system is made economically viable by the sale of lots, the elimination of institutional house construction programs, and the introduction of a labor market created by the residents themselves.

For municipal agencies, the system offers a framework for increasing health and safety standards, as well as a rational means of bringing vacant land into residential land use. This has a direct cost benefit to the city in terms of the land tax structures and in anticipating future public services expenses.

SUMMARY

Growth pole services and functions are of two types: short-term site selection and purchasing of land, and long-term technical and financial assistance.

- Short-term services include the complete site plan, the reservation of public spaces, roads, and public facilities. The ‘poles’ are small strategically located areas within this plan that received full and complete services.

- Long-term services include administrating legal titles, controlling sequence of development, supplying self-help groups with infrastructure materials and plans, and home-building loans.

The system works through two physical planning elements:

- A defined overall subdivision plan with a defined lotting pattern and reserved areas for infrastructure and community facilities.

- Full services to specific areas called ‘poles’ with a controlled sequence of selling lots at the poles and into the inter-pole areas.

The process of development follows a specific sequence:

- Poles are established by extending streets and utilities from adjacent neighborhoods.

- Pole location reflects the practicality of extending adjacent services, overall site proportions, inter-pole area sufficient for 1000 lots with primary school and playfield and walking distances to school and markets.

- Transverse roads reflect the extensions of any existing routes parallel to the contours, with best potential for developing the lower slopes first due to the lesser cost of berming, grading, and paving on a lower sloped area.

- School area and recreation field location are adjusted to the site’s topography. Mid-pole locations for the school are most favorable. Site proportions that orientate the long building axis parallel to the contours reduce the need for stairs and elevators. Recreation fields utilizing the least sloping areas for soccer or football fields are of primary interest.

- Lotting is established along the pole strips and transverse road. Parallels are retained for future pedestrian and auto circulation. Area for playfields, daycare centers, etc., are also reserved at this time.

The locations and inter-pole distances (spacing of poles) are a key to the success of development.

- A school and its associated playfields are a reasonable unit for the completed pole and infill development. Approximately a population of 6,000 is required to support a primary school.

- Walking distance of approximately 400m to the school suggests a spacing of 800m between poles.

|

|

Note: The examples shown above are from a settlement on the outskirts of Bogota, Colombia.

The layout is targeted toward slope sites, although the principles would equally apply to flat areas.

|

|

Some Examples of Proactive Intervention Strategies

|

|

Over 30 years of experience in upgrading begs the question: “What can be done to mitigate the need for upgrading. What policies are effective in preventing slums from occurring?” Two examples follow which may offer lessons for other regions.

Ouagadougo, Burkina Faso

In the mid 1980s new immigrants would be told: “Don’t squat there, it is illegal, squat here on these legal, surveyed plots.” They would be asked to pay an annual fee of 24,000 FCFA - essentially a symbolic amount. They would be registered in a telephone type of land registry, which was later incorporated into a city-wide street addressing program. The government initially trucked in water, and later water was provided by community-operated water standpipes for a fee. Latrines were mandatory and were built by the new landholders - citizens.

Lima, Peru

The Pueblos Jovenes program was carried out by SINAMOS (Sistema Nacional de Movilizacion Social) in the late 1970s. Groups of would-be landholders would get organized and carry out an overnight ‘commando-like’ action and squat on a clearly illegal site and setup an instant ‘shantytown’. Instead of sending in police to evict them, SINAMOS would relocate them to a suitable site. The government initially trucked in water, but quickly informal suppliers took over the provision.

What are common elements?

Both share the following features:

- They are low cost, easily surveyed

- No services are provided initially, but come in after the area is settled

- The settlers are actively involved in decisions and through 'sweat-equity'

- Settlers pay a small fee: it is not free

- The cities have some form of an urban structure plan or reference plan that indicates area of possible settlement

- Simple, non-cadastral registration/identification systems are used to record 'ownership'

- The settlement is legally recognized by the municipality or national government

What are potential problematic issues when transferring to other cities?

- Is land available in 'reasonable' locations that could be used for settlers? Availability implies government owned land, or land that could be purchased at low cost, and at a distance accessible to employment

- Would land speculation and sprawl be unwelcome factors to consider?

|

|

|