|

|

Setting It Up

Interactive Dwelling Design

|

|

| Families Designing Their Own Houses |

Patama Roonrakwit. Community Architects for Shelter and Environment (CASE), Bangkok, Thailand. Email: case@loxinfo.co.th

|

|

This example from Chiangmai, Thailand, illustrates an interactive, hands-on process to dwelling design. The approach highlights how professional upport is effectively transmitted, and how individual preferences are inherently incorporated while reaching a consensus at larger planning scales. The process allows participants to see the results of their own decisions and the tradeoffs which their design entails.

This approach may be used in resettlement projects, as well as in upgrading areas where the units are required to be rebuilt and the area restructured. (See also: Land Sharing)

The starting point is the aspirations of the families. Constraints are then progressively introduced and families make individual tradeoff decisions, appropriate to their circumstances and wishes. The families chose materials and the way of construction fitting to their resources. Rules for grouping of dwellings are made collectively and are self-defined.

Extensive use of self-built models, both small scale and full size, allow families to understand the spatial implications of their design decisions.

|

Background

Sixty-two families of the Santitham Community were required to move when a new road was to be built through their very low income settlement. The families were renting the property and had lived there for 25 years. They had built their dwellings and had formed a highly cohesive community.

After a protracted struggle the families convinced the National Housing Authority (NHA) to provide alternative land for resettlement. The families selected the new site, and the NHA agreed to provide paved roads, metered electric connections, storm-water drainage and a piped water supply. Each family would be granted land title after repayment of loans for the land. The houses remained the responsibility of the families and loans would be available from the Urban Community Development Office (UCDO).

The new site was approximately 5 acres which would contain 120 plots. Each plot would be 6m x 14m (84 sq.m.), appreciably smaller than their current 200 sq.m. plots.

“We had 40 people start, nearly half of whom were men. But most men dropped out, leaving the women to suspect that probably the men considered all this fussing about houses to be something unimportant, too simple for men.”

|

|

|

The Process

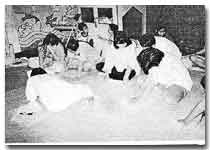

1 - Getting Started: Understanding the Community and Building Awareness

The architect went to the community to talk with the people and to get an idea of how they lived, what they wanted and what kind of resources they had for constructing the new dwellings. Families were asked to make sketches of their houses and add comments on space and functions.

“People are always shy, especially in Northern Thailand, so we talked about all the difficulties of making shelter in the city for a family with very little money and no land. We talked about how they do it, how did they use their houses, what parts are the most important, and what changes had they made. I tried to connect the discussion with issues of space and function.”

Output: Families were more aware of their considerable experience in designing and building their current houses, what was important to them and what improvements could be made in the new houses.

|

|

2 - Making ‘Dream Houses’

In a second workshop each family was invited to draw their dream without worrying about budget or size.

“Despite the invitation to go wild, most squeezed all of the family's needs into houses that kept within the limits of extremely modest plot sizes and budgets. No castles, no palaces, only two houses with home-cinema!”

Output: Base design of aspirations on which final designs can be developed. Families have a sense of what their dreams imply in reality.

|

|

|

3 - Making It Real: Adding Space Constraints

The 6m x 14 m plot was sketched on grid paper and their ‘dream house’ was squeezed into the plot by the families. Families were given scaled cut-out furniture to stick on the plan. The furniture gave scale and provided a sense if the spaces would work. Families were then asked to make a rough 3 dimensional model out of cardboard.

“We used the floor tiles of the room that we were in to help visualize the life-size scale that the grid paper represented.”

Output: Sketch and model of house. drawn to scale, modified to plot size Families now more aware of size constraints.

|

|

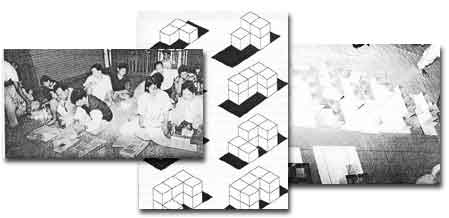

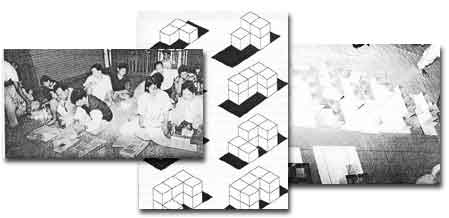

4 - Building Community Level Awareness

The models were placed together on the site plan. Discussions were held on what form their community should be and agreements were made on setbacks, density, and open space. The house designs were then readjusted to meet the community goals.

“Suddenly we had a community in front of us and it looked awful! Their was no open space, one roof drained on another roof, not place for trees or air circulation. It was packed! When I asked if they would like to live there, there was a chorus of No’s.”

Output: Preliminary site plan and agreements on setbacks, and open spaces. Adjusted house designs to conform to site agreements.

|

|

|

5 - Refining the Plan: Adjusting to Size Constraints

Families were grouped into those with similar family sizes and budget constraints so they could borrow ideas from one another and help develop house designs. A modular of 3m x 3m and 2.5m height was adopted as the basic element, which fits a standard room size and which could be conveniently built and spanned using locally available bamboo. These 'structural units' were made in cardboard and used by families to redesign their units. The resultant houses were placed on the site plan to again test and evaluate how they act as a community.

“All the houses were completely different in area, orientation, massing and function and the people were all happy with their ideas. When placed on the site plan, they could imagine themselves living there, and everyone was satisfied with the sense of community they had created.”

Output: Refined set of house designs, based on a 3m x 3m module. Site plan of community.

|

|

|

6 - Determining Costs of Materials and Construction

A simple table for estimating costs was given to each family in which to list materials and quantities needed for their new houses. They took in consideration what could be salvaged from their existing house, and then they decided what new materials would be needed and how much they would cost. Slides were shown of houses around the world with unconventional materials - bamboo, thatch, scrap wood, and cloth to give them another reference in deciding how to proceed.

They then divided into groups and went throughout the city to gather information about prices and availability. These were then incorporated into their cost estimates of their house.

“I did not have to persuade anyone to use cheaper ‘local materials’ rather than the more costly metal and concrete, which are symbolic of middle-class affluence. They figured out for themselves that using these materials make their houses too expensive. People understood their limitations and reality was the best decider. This does not mean not to use concrete or metal, but considering the hefty land-loan payments it makes sense to avoid deeper debt as much as possible. Gradually houses can be upgraded, as families can afford to do so.”

Output: List of materials for construction of their house and the estimated costs.

|

|

|

Conclusions

Families who participated in the workshops had more options and a broader understanding about how to build an appropriate, inexpensive house that suits the family’s needs.

Families understand their own situation best, and draw on their own experiences and build in their own way according to what works for them. Ready-made professional plans often end up scrapped, ignored, radically altered or are often even inappropriate and a disservice.

The approach illustrated balances the input from the professional practitioner with the realities and experience of the individual families, each contributing as equal partners.

“Houses are now built and families have moved in. Not unexpectedly the designs do not follow the workshop designs to the letter - real life conditions are messy!”

|

|

|

|

|

|