|

Project Amazonia: Characterization - Biotic - Epiphytes Introduction Epiphytes or arboreal flora constitute an integral part of the rainforest ecosystem and are the most sensitive among the flora to climatic change. Vascular epiphytes (such as those living on bark), residing primarily in pre-montane to mid-montane forests, comprise 10% of epiphyte species, yet the majority of those in the forest canopy1. Non-vascular epiphytes (mosses, liverworts, and lichens) require specific timing on wet dry cycles to flourish, and are much more acutely affected by variations in climate (such as changes in the patterns of annual and seasonal rainfall) than their vascular counterparts. All epiphytes, however, are distributed throughout the canopy on the basis of water supply. Within vascular epiphytes, there are:

Non-vascular epiphytes include:

The availability of moisture affects the diversity, abundance and distribution of non-vascular and vascular epiphytes (although the latter is less sensitive).1

Epiphytes play a key role in the rainforest ecosystem. They provide nectar, pollen, fruit and seed for harvest, and their moisture and nutrient retaining properties are essential to many of the terrestrial invertebrates and lower vertebrates. Some epiphytes have developed coevolved mutualisms with fauna, for example within an ant-nest garden, the ants provide a home for the epiphytes, while the epiphytes remove harmful excess moisture from the nest. They also provide an important source of biomass (storage capacity). Epiphytes are important in rainforest hydrology and mineral cycles. They are well equipped to absorb the prevailing horizontal precipitation (in the form of fog water). They also vastly increase the canopy foliage surface area which absorbs ions and moisture (some data indicates that up to half of the canopy's macronutrients may be contained in epiphytes1). Epiphytes behave as storage facilities and capacitors for other rainforest biota, as they release certain ions at some points in the year, and absorb the same ions at others. Dead epiphytes contribute to the soil-recharging litter of the forest floor.

Adaptation to drought:

In general, epiphyte species composition and biomass are much more sensitive to different relative moisture levels than those of other flora. The effects on different forests and certain regions of the same forest due to change in climate vary according to the types of epiphytes in these regions. Higher CO2 concentrations allow C3 and CAM epiphytes to fix carbon with less transpiration, but the scientific community is still not sure of exactly how this would change competitive patterns between species.

A change in the climate large enough to only affect epiphytes would nonetheless change the entire forest in terms of its "physical structure, biodiversity, and patterns of energy, water, and nutrient flux" in addition to "ecosystem stability and resiliency."1 Epiphytes and Fragmentation:

Basic Info on Fragmentation: Epiphytes as Bioindicators Epiphytes and orchids are well suited to be indicators of the health and biodiversity of the rainforest, not only because they are an important source of nutrients for other flora and fauna, but because they are very sensitive to shifts in microclimate and they have slow growth. The performance, survival, and distribution of epiphytes is dependent on stand density, microclimate, distance from seed source, tree size and species, type and history of disturbance, population dynamics of epiphytes and trees, and epiphyte physiology.2

Epiphytes are far more vulnerable to deforestation than other

flora. For example, 26% of vascular plant species present in 1900 are now

extinct, but 62% of epiphyte species are extinct.2

Epiphytes are completely dependent on their host plants, so if a tree is cut

down, all of the epiphytes residing on that tree will die. In addition, they

have very specific zoning constraints, so secondary vegetation might not

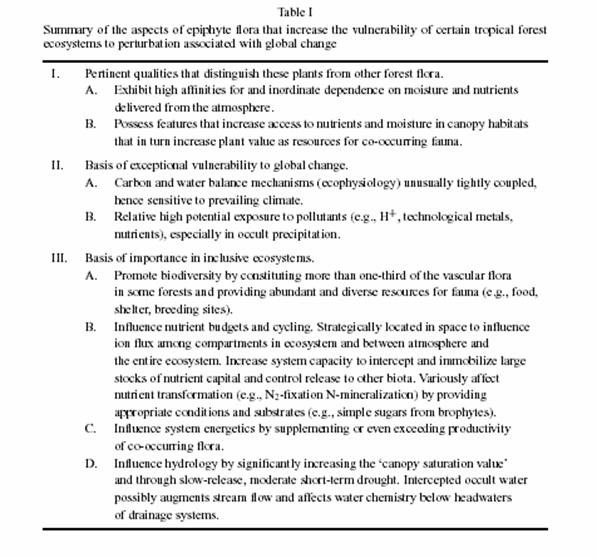

have all of the necessary microsites for different epiphyte species. Table 12 illustrates the loss of species and biodiversity in a plantation as compared with oldgrowth forest. While the number of species for the two groups is not very different, there is considerable loss of biodiversity, because only epiphytes residing in some of the locations on a tree are present.

Below are a couple of specific species or groups have been identified as good bioindicators.

Epiphytes obtain their Nitrogen either from canopy soil or from nutrients in rainwater. Nitrogen-15 concentration is much higher in ground-rooted plants than in epiphytes with access to canopy soil, pointing to a much richer source of Nitrogen in terrestrial soil versus canopy soil. In addition, N-15 concentration is much higher for those epiphytes in canopy soil than those on smaller branches, indicating that epiphytes on smaller branches have to rely almost exclusively on rainwater as a source of Nitrogen.3 This means that these epiphytes (on small branches) are much more susceptible to drought and thus would be better bioindicators.

1: Benzing, David H. "Vulnerabilities of Tropical Forests to Climate Change: the Significance of Resident Epiphytes." Climatic Change. 1998. Volume 39: Issue 2-3, pgs 519-540. 2: Hietz, Peter. "Diversity and Conservation of Epiphytes in a Changing Environment." International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). 1998. Volume 70: Issue 11. Available at: http://www.iupac.org/symposia/proceedings/phuket97/hietz.html 3: Hietz, Peter; Wanck, Wolfgang; Wania, Rita; Nadkarni, Nalim M. "Nitrogen-15 natural abundance in a montane cloud forest canopy as an indicator of nitrogen cycling and epiphyte nutrition." Oecologia. 2002. Volume 131, pgs. 350-355. 4: Lambert, Frank R. and Marshall, Adrian G. "Keystone characteristics of Bird-dispersed Ficus in a Malaysian lowland Rain Forest." Journal of Ecology. 1991. Volume 79, pgs. 793-809. 5: Ranta, Pertti; Blom, Tom; Niemela, Jari; Joensuu, Elina and Siitonen, Mikko. "The fragmented Atlantic rain forest of Brazil: size, shape and distribution of forest fragments." Biodiversity and Conservation. 1998. Volume 7, pgs. 385-403. 6: Turner, I.M.; Chua, K.S.; Ong, J.S.Y.; Soong, B.C.; Tan, H.T.W. "A century of plant species loss from an isolated fragment of lowland tropical rainforest." Conservation Biology. August 1996. Volume 10: Issue 4, pgs. 1229-1244. |

1

1