Subsections

2.4 Specific Heats: the relation between temperature change and heat

[VW, S& B: 5.6]

How much does a given amount of heat transfer change the temperature

of a substance? It depends on the substance. In general

|

(2..4) |

where  is a constant that depends on the substance. We can

determine the constant for any substance if we know how much heat is

transferred. Since heat is path dependent, however, we must specify

the process, i.e., the path, to find

is a constant that depends on the substance. We can

determine the constant for any substance if we know how much heat is

transferred. Since heat is path dependent, however, we must specify

the process, i.e., the path, to find  .

.

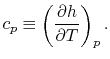

Two useful processes are constant pressure and constant volume, so

we will consider these each in turn. We will call the specific heat

at constant pressure  , and that at constant volume

, and that at constant volume  , or

, or

and

and  per unit mass.

per unit mass.

- The Specific Heat at Constant Volume

Remember that if we specify any two properties of the system, then

the state of the system is fully specified. In other words we can

write

,

,  or

or  . [VW, S & B: 5.7]

. [VW, S & B: 5.7]

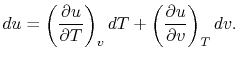

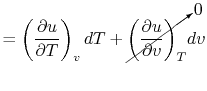

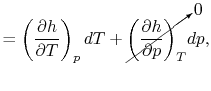

Consider the form

, and use the chain rule to write how

, and use the chain rule to write how

changes with respect to

changes with respect to  and

and  :

:

|

(2..5) |

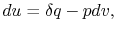

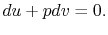

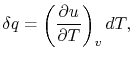

For a constant volume process, the second term is zero since there

is no change in volume,  . Now if we write the First Law for

a quasi-static process, with

. Now if we write the First Law for

a quasi-static process, with  ,

,

|

(2..6) |

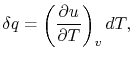

we see that again the second term is zero if the process is also

constant volume. Equating (2.5) and

(2.6) with  canceled in each,

canceled in each,

|

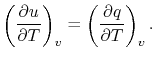

|

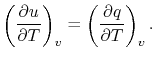

and rearranging

|

|

|

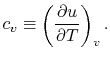

In this case, any energy increase is due only to energy transfer as

heat. We can therefore use our definition of specific heat from

Equation (2.4) to define the specific

heat for a constant volume process,

- The Specific Heat at Constant Pressure

If we write  , and consider a constant pressure process, we

can perform a similar derivation to the one above and show that

, and consider a constant pressure process, we

can perform a similar derivation to the one above and show that

In the derivation of  , we considered only a constant volume

process, hence the name, ``specific heat at constant volume.'' It is

more useful, however, to think of

, we considered only a constant volume

process, hence the name, ``specific heat at constant volume.'' It is

more useful, however, to think of  in terms of its definition

as a certain partial derivative, which is a thermodynamic property,

rather than as a quantity related to heat transfer in a special

process. In fact, the derivatives above are defined at any

point in any quasi-static process whether that process is constant

volume, constant pressure, or neither. The names ``specific heat

at constant volume'' and ``specific heat at constant pressure'' are

therefore unfortunate misnomers;

in terms of its definition

as a certain partial derivative, which is a thermodynamic property,

rather than as a quantity related to heat transfer in a special

process. In fact, the derivatives above are defined at any

point in any quasi-static process whether that process is constant

volume, constant pressure, or neither. The names ``specific heat

at constant volume'' and ``specific heat at constant pressure'' are

therefore unfortunate misnomers;  and

and  are thermodynamic

properties of a substance, and by definition depend only the state.

They are extremely important values, and have been experimentally

determined as a function of the thermodynamic state for an enormous

number of simple compressible substances2.1.

are thermodynamic

properties of a substance, and by definition depend only the state.

They are extremely important values, and have been experimentally

determined as a function of the thermodynamic state for an enormous

number of simple compressible substances2.1.

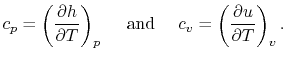

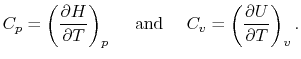

To recap:

or

Practice Questions

Throw an object from the top tier of the lecture hall to

the front of the room. Estimate how much the temperature of the room

has changed as a result. Start by listing what information you need

to solve this problem.

The equation of state for an ideal gas is

where  is the number of moles of gas in the volume

is the number of moles of gas in the volume  . Ideal gas

behavior furnishes an extremely good approximation to the behavior

of real gases for a wide variety of aerospace applications. It

should be remembered, however, that describing a substance as an

ideal gas constitutes a model of the actual physical

situation, and the limits of model validity must always be kept in

mind.

. Ideal gas

behavior furnishes an extremely good approximation to the behavior

of real gases for a wide variety of aerospace applications. It

should be remembered, however, that describing a substance as an

ideal gas constitutes a model of the actual physical

situation, and the limits of model validity must always be kept in

mind.

One of the other important features of an ideal gas is that its

internal energy depends only upon its temperature. (For now, this

can be regarded as another aspect of the model of actual systems

that the ideal gas represents, but it can be shown that this is a

consequence of the form of the equation of state.) Since  depends

only on

depends

only on  ,

,

In the above equation we have indicated that  can depend on

can depend on

. Like the internal energy, the enthalpy is also only dependent

on

. Like the internal energy, the enthalpy is also only dependent

on  for an ideal gas. (If

for an ideal gas. (If  is a function of

is a function of  , then, using

the ideal gas equation of state,

, then, using

the ideal gas equation of state,  is also.)

Therefore,

is also.)

Therefore,

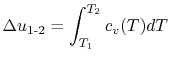

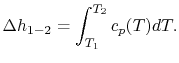

If we are interested in finite changes of internal energy or

enthalpy, we integrate,

and

Over small temperature changes (

),

it is often assumed that

),

it is often assumed that  and

and  are constant. Furthermore,

there are wide ranges over which specific heats do not vary greatly

with respect to temperature, as shown in SB&VW Figure 5.11. It is

thus often useful to treat them as constant. If so

are constant. Furthermore,

there are wide ranges over which specific heats do not vary greatly

with respect to temperature, as shown in SB&VW Figure 5.11. It is

thus often useful to treat them as constant. If so

These equations are useful in calculating internal energy or

enthalpy differences, but it should be remembered that they hold

only if the specific heats are constant.

We can relate the specific heats of an ideal gas to its gas constant

as follows. We write the first law in terms of internal energy,

and assume a quasi-static process so that we can also write it in

terms of enthalpy, as in

Section 2.3.4,

Equating the two first law expressions above, and assuming an ideal

gas, we obtain

Combining terms,

Since  ,

,

An expression that will appear often is the ratio of specific heats,

which we will define as

Below we summarize the important results for all ideal gases, and

give some values for specific types of ideal gases.

- All ideal gases:

- The specific heat at constant volume (

for a unit mass or

for a unit mass or  for one kmol) is a function of

for one kmol) is a function of  only.

only.

- The specific heat at constant pressure (

for a unit mass or

for a unit mass or  for one kmol) is a function of

for one kmol) is a function of  only.

only.

- A relation that connects the specific heats

,

,  , and the gas constant is

, and the gas constant is

where the units depend on the mass considered. For a unit

mass of gas, e.g., a kilogram,  and

and  would be the

specific heats for one kilogram of gas and

would be the

specific heats for one kilogram of gas and  is as defined above.

For one kmol of gas, the expression takes the form

is as defined above.

For one kmol of gas, the expression takes the form

where  and

and  have been used to denote the specific heats

for one kmol of gas and

have been used to denote the specific heats

for one kmol of gas and

is the universal gas

constant.

is the universal gas

constant.

- The specific heat ratio,

(or

(or  ), is a function of

), is a function of  only and is greater than unity.

only and is greater than unity.

- An ideal gas with specific heats independent of temperature,

and

and

, is referred to as a perfect gas. For example, monatomic gases

and diatomic gases at ordinary temperatures are considered perfect

gases. To make this distinction the terminology "a perfect gas with

constant specific heats" is used throughout the notes. In some

textbooks perfect gases are sometimes also referred to as ideal

gases, and to avoid confusion we use the stated

terminology2.2.

, is referred to as a perfect gas. For example, monatomic gases

and diatomic gases at ordinary temperatures are considered perfect

gases. To make this distinction the terminology "a perfect gas with

constant specific heats" is used throughout the notes. In some

textbooks perfect gases are sometimes also referred to as ideal

gases, and to avoid confusion we use the stated

terminology2.2.

- Monatomic gases, such as He, Ne, Ar, and most metallic vapors:

(or

(or  ) is constant over a wide temperature range and is very nearly equal to

) is constant over a wide temperature range and is very nearly equal to  [or

[or

, for one kmol].

, for one kmol].

(or

(or  ) is constant over a wide temperature range and is very nearly equal to

) is constant over a wide temperature range and is very nearly equal to  [or

[or

, for one kmol].

, for one kmol].

is constant over a wide temperature range and is very nearly equal to

is constant over a wide temperature range and is very nearly equal to  [

[

].

].

- So-called permanent diatomic gases, namely H

, O

, O , N

, N ,

Air, NO, and CO:

,

Air, NO, and CO:

(or

(or  ) is nearly constant at ordinary temperatures, being approximately

) is nearly constant at ordinary temperatures, being approximately  [

[

,

for one kmol], and increases slowly at higher temperatures.

,

for one kmol], and increases slowly at higher temperatures.

(or

(or  ) is nearly constant at ordinary temperatures, being approximately

) is nearly constant at ordinary temperatures, being approximately  [

[

,

for one kmol], and increases slowly at higher temperatures.

,

for one kmol], and increases slowly at higher temperatures.

is constant over a temperature range of roughly

is constant over a temperature range of roughly

to

to

and is very nearly equal to

and is very nearly equal to  [

[

]. It decreases with temperature above this.

]. It decreases with temperature above this.

- Polyatomic gases and gases that are chemically active, such as CO

, NH

, NH , CH

, CH , and Freons:

, and Freons:

The specific heats,  and

and  , and

, and  vary with the

temperature, the variation being different for each gas. The general

trend is that heavy molecular weight gases (i.e., more complex gas

molecules than those listed in 2 or 3), have values of

vary with the

temperature, the variation being different for each gas. The general

trend is that heavy molecular weight gases (i.e., more complex gas

molecules than those listed in 2 or 3), have values of  closer to unity than diatomic gases, which, as can be seen above,

are closer to unity than monatomic gases. For example, values of

closer to unity than diatomic gases, which, as can be seen above,

are closer to unity than monatomic gases. For example, values of

below 1.2 are typical of Freons which have molecular

weights of over one hundred.2.3

below 1.2 are typical of Freons which have molecular

weights of over one hundred.2.3

In general, for substances other than ideal gases,  and

and  depend on pressure as well as on temperature, and the above

relations will not all apply. In this respect, the ideal gas is a

very special model.

depend on pressure as well as on temperature, and the above

relations will not all apply. In this respect, the ideal gas is a

very special model.

In summary, the specific heats are thermodynamic properties and can

be used even if the processes are not constant pressure or constant

volume. The simple relations between changes in energy (or enthalpy)

and temperature are a consequence of the behavior of an ideal gas,

specifically the dependence of the energy and enthalpy on

temperature only, and are not true for more complex

substances.2.4

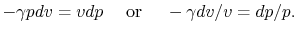

2.4.2 Reversible adiabatic processes for an ideal gas

From the first law, with  ,

,

, and

, and

,

,

|

(2..7) |

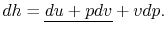

Also, using the definition of enthalpy,

|

(2..8) |

The underlined terms are zero for an adiabatic process. Rewriting

(2.7) and (2.8),

Combining the above two equations we obtain

|

(2..9) |

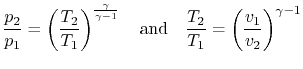

Equation (2.9) can be integrated between states 1 and 2

to give

For an ideal gas undergoing a reversible, adiabatic

process, the relation between pressure and volume is thus:

We can substitute for  or

or  in the above result using the ideal

gas law, or carry out the derivation slightly differently, to also

show that

in the above result using the ideal

gas law, or carry out the derivation slightly differently, to also

show that

We will use the above equations to relate pressure and temperature

to one another for quasi-static adiabatic processes (for instance,

this type of process is our idealization of what happens in

compressors and turbines).

Practice Questions

- On a

-

- diagram for a closed-system sketch the

thermodynamic paths that the system would follow if expanding from

diagram for a closed-system sketch the

thermodynamic paths that the system would follow if expanding from

to

to

by isothermal and

quasi-static, adiabatic processes.

by isothermal and

quasi-static, adiabatic processes.

- For which process is the most

work done by the system?

- For which process is there heat exchange?

Is it added or removed?

- Is the final state of the system the same

after each process?

- Derive expressions for the work done by the

system for each process.

Douglas Quattrochi

2006-08-06

|

![]() , and consider a constant pressure process, we

can perform a similar derivation to the one above and show that

, and consider a constant pressure process, we

can perform a similar derivation to the one above and show that

![]() , we considered only a constant volume

process, hence the name, ``specific heat at constant volume.'' It is

more useful, however, to think of

, we considered only a constant volume

process, hence the name, ``specific heat at constant volume.'' It is

more useful, however, to think of ![]() in terms of its definition

as a certain partial derivative, which is a thermodynamic property,

rather than as a quantity related to heat transfer in a special

process. In fact, the derivatives above are defined at any

point in any quasi-static process whether that process is constant

volume, constant pressure, or neither. The names ``specific heat

at constant volume'' and ``specific heat at constant pressure'' are

therefore unfortunate misnomers;

in terms of its definition

as a certain partial derivative, which is a thermodynamic property,

rather than as a quantity related to heat transfer in a special

process. In fact, the derivatives above are defined at any

point in any quasi-static process whether that process is constant

volume, constant pressure, or neither. The names ``specific heat

at constant volume'' and ``specific heat at constant pressure'' are

therefore unfortunate misnomers; ![]() and

and ![]() are thermodynamic

properties of a substance, and by definition depend only the state.

They are extremely important values, and have been experimentally

determined as a function of the thermodynamic state for an enormous

number of simple compressible substances2.1.

are thermodynamic

properties of a substance, and by definition depend only the state.

They are extremely important values, and have been experimentally

determined as a function of the thermodynamic state for an enormous

number of simple compressible substances2.1.

![]() depends

only on

depends

only on ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() , and

, and ![]() vary with the

temperature, the variation being different for each gas. The general

trend is that heavy molecular weight gases (i.e., more complex gas

molecules than those listed in 2 or 3), have values of

vary with the

temperature, the variation being different for each gas. The general

trend is that heavy molecular weight gases (i.e., more complex gas

molecules than those listed in 2 or 3), have values of ![]() closer to unity than diatomic gases, which, as can be seen above,

are closer to unity than monatomic gases. For example, values of

closer to unity than diatomic gases, which, as can be seen above,

are closer to unity than monatomic gases. For example, values of

![]() below 1.2 are typical of Freons which have molecular

weights of over one hundred.2.3

below 1.2 are typical of Freons which have molecular

weights of over one hundred.2.3

![]() and

and ![]() depend on pressure as well as on temperature, and the above

relations will not all apply. In this respect, the ideal gas is a

very special model.

depend on pressure as well as on temperature, and the above

relations will not all apply. In this respect, the ideal gas is a

very special model.

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() ,

,

![]() or

or ![]() in the above result using the ideal

gas law, or carry out the derivation slightly differently, to also

show that

in the above result using the ideal

gas law, or carry out the derivation slightly differently, to also

show that