| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |

| Vol.

XVI No.

5 April / May 2004 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

From The Faculty Chair

FPC Statement on Representation of Minorities

In the last Faculty Newsletter I discussed issues related to faculty governance. In that article I wrote: "The Faculty Policy Committee, the over-arching committee in the existing (faculty governance) structure, has the charge to "maintain a broad overview of the Institute's academic programs, deal with a wide range of policy issues of concern to the Faculty, and coordinate the work of the faculty committees". Very quickly FPC finds itself playing the role of the gatekeeper to the faculty meetings, giving final approval to recommendations by other committees, or serving as a sounding board of ideas arising largely from the administration. Indeed, that is a necessary function but what is lacking is the strategizing role, the faculty body who can think of issues and define positions to be taken by the faculty which in turn can help and guide the administration." The existing Faculty Policy Committee decided to spend a fair amount of its time being pro-active in the formulation of policy, developing positions that would hopefully influence Institute policy. Following is a white paper, a set of recommendations, resulting from addressing the faculty diversity issue. We hope that all faculty read this carefully. Changes in the composition of the faculty will only occur when we modify our attitudes and bring the issue to the forefront of our hiring practices.

The members of the Faculty Policy Committee who have contributed to this piece are: Rafael L. Bras, Paola Rizzoli, Ken Manning, Kirk Kolenbrander, Lorna Gibson, Vijay Kumar, Anne McCants, Ernst Berndt, Mary Fuller, Ahmed Ghoniem, Leslie Norford, Yun-Ling Wong ('04), and Krishnan Sriram (G).

Faculty Policy Committee

Statement on Representation of Minorities on the Faculty and

in the Graduate Student Body

Introduction

The Faculty Policy Committee considers diversity in the professoriate, the student body, and the staff an issue of strategic importance to MIT. FPC takes for granted the arguments of equal opportunity, justice, and the socio-cultural value of a learning environment representative of the larger community. FPC is also convinced that our commitment to excellence and our proud adherence to the recognition and promotion of merit require that we reach out to a more diverse community.

The percentage of underrepresented minorities (African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans) and women in the science and engineering workforce is less than half of what it should be relative to the overall population (The Talent Imperative: Diversifying America's Science and Engineering Workforce, Building Engineering and Science Talent (BEST), 401 B St., Suite 2200, San Diego, CA, April 2004). Demographics would seem to indicate that this situation would probably grow worse in the foreseeable future. If MIT fails to get the best of this "missing population," then we will be also missing the fastest growing pool of talent in the nation and ultimately will be unrepresentative of the groups that will become the economic engine of the United States. Already over 35% of the professoriate in engineering, 25% in mathematics and computer sciences, and 20% in the physical sciences are foreign-born (National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2000, report NSB-00-01, National Science Foundation). Without this reliance on the best and the brightest from other parts of the world, the nation will have difficulty staffing higher education and research in science and engineering. But as opportunities develop in this increasingly integrated world, this source of foreign-born brainpower can be expected to diminish. Our hope (and obligation) is to educate and hire from the largest group, and the largest untapped source of talent, in our own population: women and underrepresented minorities.

This document is written with the explicit understanding that when the term "minority candidate" is used, the authors assume that such a person is qualified by criteria MIT applies in its selection for all candidates for a given position. Only qualified individuals hold positions at MIT, whatever the race. While our focus is on underrepresented faculty as defined by the Institute in its policies, we note that in some areas and schools Asians are not adequately represented on the faculty in particular areas, especially in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, given the composition of Asian students in the undergraduate population.

| Back to top |

An Assessment of the Present

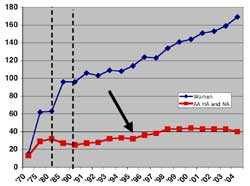

The following three figures summarize the representation of women and underrepresented minorities on the MIT faculty and in the student body. The first figure shows the time history of the number of women in the faculty with the number of underrepresented minorities in the faculty. The number of women faculty shows a steady growth, particularly since 1998-99, although examination of this figure and the next also reveals that it will be many decades before the percentage of women faculty equals the percentage of women in the pipeline (defined as women receiving PhDs.)

The graph showing the number of minority faculty is more discouraging. This number remains stagnant, and is not even at its all-time high at present. The stagnation reflects limited hiring and limited success in the promotion of underrepresented minorities.

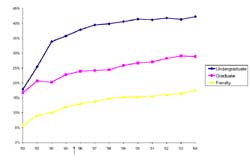

The second figure shows that the undergraduate population exhibits a significant growth in the number of women. The graduate population also has grown, initially not as quickly, but at a healthy pace that parallels growth in the women faculty ranks.

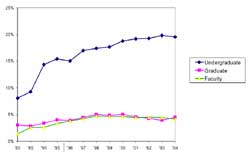

The third figure tells a different story. The percentage of underrepresented minorities has grown (there is a hint of stagnation lately) in the undergraduate population, but there is no percentage growth in the graduate population, which is as flat as the minority faculty time history. It should be noted that the absolute number of underrepresented minorities in the graduate student body has increased (from about 200 in 1994 to about 280 now), but that it has not kept pace with the increase in the graduate student body during the same period.

There is an undeniable correlation between the momentum of recruitment and hiring of women to the faculty and the graduate student body and the emergence of uncompromising leadership among the women faculty, as represented by the Women in Science report of 1999 and reports from each of the five schools that led to the establishment of the five Gender Equity Committees. This movement accomplished the documentation of problems, the rallying of the women faculty behind a cause, and the admission by the MIT administration that a problem existed and needed to be addressed. Since then, gender has been a more visible issue in many decisions within the Institute. We now need to stimulate the same kind of momentum on the minority faculty issue-namely, collect data and interview both minority students and faculty to identify key issues that may help to explain our failure to make progress. Then, through collaboration with faculty colleagues in the various departments and members of the administration, we must take steps to address the issues identified.

Strategies for Change

It is too easy to attribute the small number of minorities in the faculty solely to a pipeline issue. The argument is that there are not enough qualified candidates to fill the available positions, and that there is therefore a dearth of minority applicants for open positions. But although the pipeline is leaky between undergraduate and graduate education, in terms of underrepresented minorities nationwide, it is not empty. FPC believes that there are qualified candidates available. Being very generous in the counting, there are now some 40 underrepresented minorities on the MIT faculty. Hiring even 3-4 individuals a year (less than 10 percent of our annual hiring) would make a significant difference. MIT alone has 280 underrepresented minority graduate students, and other academic institutions around the country have similar numbers. Few would dispute the fact that some fields are reasonably well-populated by minorities nationwide. Even accounting for the poor historic performance of academic institutions in educating minorities, there is enough of a pool nationwide to break the inertia in minority hiring at MIT. But to find the top candidates that we want, we must begin by making ourselves attractive and welcoming to minorities. So far, we have not done so. Recruiting the best minds is never a "business as usual" exercise. Recruiting the best minority faculty candidates, however, requires even harder work and increased willingness to compete.

A strategy to change the composition of the faculty and the graduate student body must be multi-dimensional and strongly supported throughout the Institute, at both the grass-roots efforts of the faculty and the upper levels of the administration. Following are a few propositions and action items in several important dimensions.

| Back to top |

Commitment from Below

Faculty in the departments and academic units are the first and foremost effective agents for recruiting, hiring, and retaining minority faculty.

– Each faculty member must accept responsibility to bring minority candidates within his or her profession, or through other appropriate networks, to the attention of his or her MIT colleagues, department head, and dean in routine searches, as well as for appointments as targets of opportunity.

– Each faculty member should strive to insure that all searches within his or her department give due attention to equal opportunity for minority candidates.

– Colleagues in every academic unit should strive to insure the success of minority faculty through appropriate mentoring and guidance throughout the faculty member's career, especially in the early stages.

– Faculty members should be recognized and rewarded on an individual basis by the department head, dean, and upper-level administration for outstanding efforts to attract, recruit, and retain minority faculty.

Commitment at the Top

The evidence indicates that one of the most effective ways to overcome the inertia of recruitment, hiring, and retention of minorities is for the leadership to signal unequivocally their commitment to the solution of the problem, with attendant consequences and rewards.

– The upper-level administration must repeatedly convey the message, in word and deed, that minority recruitment is a very important issue. This involves open debate and discussion in every possible forum.

– Deans must be unwavering and uncompromising with departments and their leaders about the seriousness of the need to hire minorities. This worked well in the case of women hires, finally convincing some units that excellence was staring them in the eye from among the female ranks.

– The appointment and evaluation of department heads should explicitly consider performance in minority recruitment and retention.

– Minority recruits should have advocates at the highest level of MIT's decision-making and policy-setting bodies; such advocates should be tasked with "problem solving," for example, when issues arise with a potential hire.

Information

We must collect and make available better information both to understand the current situation and to identify where improvements are possible.

– Coordinate efforts on behalf of minority recruitment and retention more effectively.

– Maintain and provide access to accurate data on minority applicants to graduate school, admission rate, and yield.

– Develop a wide array of information on recruitment, including a clearinghouse of information on resources available at MIT and elsewhere.

– Maintain and provide access to centralized information on minority faculty applicants, interviews, outcomes, and promotion histories.

– Gather information on failures to attract students and faculty, including feedback from candidates on their reasons for declining offers.

– Develop and make available a manual of "best practices" for recruitment of minorities at all levels.

Recruitment and Retention of Faculty

As already stated, minority faculty recruitment and retention require an unequivocal message from the top: we want minority hires, men and women. This process can begin by collecting and publishing data relative to minorities at MIT, including issues of retention and promotion, salary, space, leadership roles, etc. Some other general recommendations have been given already.

Action items

– Implement the Council for Faculty Diversity "pipeline proposal," available from the Council.

– Track the progress of all minorities in science and technology, and in the humanities and social sciences.

– Consider making an initial aggressive move to hire in areas identified as not having a pipeline problem (the Council on Faculty Diversity should identify these areas).

– Consider establishing a program to provide postdoctoral experience funds, not at MIT, for individuals whom we are willing to hire once they acquire additional experience.

– Revisit the use of the MLK program as a recruitment tool.

– Require a priori justification of search committee for not interviewing minority faculty candidates.

– Be willing to hire our own minority graduates.

– Insure that all serious minority candidates meet with members of the senior administration, to make it clear that MIT wants them.

– Provide generous start-up funds.

– Publish best practices and celebrate successes.

– Develop an effective mentoring system, realizing that there are not enough senior minority faculty to mentor new minority hires.

– Create a more transparent promotion process and a way to audit the process through appropriate checks and balances.

– Seek out minority faculty for influential positions within departments and the central administration (department heads, members and chairs of key committees).

– Involve tenured minorities in the selection of administrators.

– Watch for and intervene to prevent the isolation and marginalization of minorities that frequently occur, particularly after tenure.

| Back to top |

Recruitment and Retention of Graduate Students

Our success in recruiting undergraduates is largely due to the fact that undergraduate admissions are controlled and governed by the Institute's central policies. The decentralized nature of graduate admissions, however, makes it difficult to apply central policies in a uniform way. This is exacerbated by the inability of the Office of Graduate Education to acquire all the information it needs about admission decisions from the responsible academic departments. A strategy for improving graduate student recruitment would include the following elements:

– Move the system closer to some centralized responsibility with respect to data collection, outreach, improvement of yield, targeted resource allocation, and retention efforts.

– Develop a feeder system of mutually trusted institutions.

– Collaborate with institutions that often hire our students and from which we hire.

– Make our environment friendlier to minorities, including provision of services now available primarily to undergraduates.

– Improve yields of admitted students.

Action items

– Reformulate the standing committees helping to formulate policy on graduate education. The Office of Graduate Education must have increased clout and resources.

– Require that information on admissions decisions, particularly relative to minority candidates, be shared with the Office of Graduate Education.

– Require explanations for each minority-candidate decision, and supply courtesy explanations to supporters of candidates from institutions we wish to cultivate.

– Invite all accepted minorities to visit the campus.

– Identify a few feeder undergraduate institutions and develop a trustworthy collaboration with them.

– Be more aggressive in exerting a presence at venues frequented by undergraduate minority students (GEM, HENAAC, etc.) in order to dispel the perception that we are unfriendly, inaccessible, arrogant, and do not want them.

– Provide centralized support for minority graduate students (OME is largely undergraduate-focused).

– Compile and disseminate best practices of recruitment, admission, yield management and retention.

– Institutionalize and expand the summer research program.

– Change departmental policies that place our own minority undergraduate students at a disadvantage in competing for slots in MIT's graduate programs.

– Implement the Council for Faculty Diversity "pipeline proposal."

Summary

The FPC considers the recruitment of underrepresented minorities to the graduate student body and the faculty an issue of major importance for MIT. There is a lot to be learned from the experience of women at MIT. This white paper outlines some ideas that should be improved on, followed, or implemented. The one clear message, though, is that change requires unequivocal support and strong leadership from the upper levels of the administration. Members of the minority community must also play a leadership role, as their experience and advice are critical to understanding the issues. Progress towards a greater level of diversity will require the effort of all faculty, minority and nonminority alike.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |