| Vol.

XVIII No.

4 March/April 2006 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

International Students at MIT Post 9/11

Have increased security measures affected our student population?

There has been concern expressed across the Institute about the potential effects of the U.S. government’s post-9/11 security measures on international students. The good news is that international students continue to apply to and matriculate at MIT in significant numbers. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we did not see our numbers plummet, as did many schools across the nation.

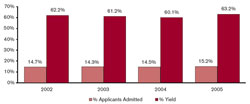

A quarter of the students at MIT are international; nearly 37% of graduate students are international. Those percentages have remained fairly constant over the past 10 years. Numbers of students from specific countries have fluctuated slightly over the years. Currently, the numbers for Canada and the United Kingdom are down, while India’s and Korea’s have increased. (See M.I.T. Numbers.) International graduate applications declined noticeably in 2004, but those numbers are beginning to recover, climbing again in 2005. (Source: Office of the Provost, Institutional Research.)

MIT still retains its enormous appeal to the best and brightest around the world in nearly all science and engineering fields. In spite of onerous post-9/11 visa regulations and processes, our students do secure their visas and arrive with very little trouble. In 2002, nearly 100 of our international students were subjected to extra security clearance procedures, eliciting significant visa delays. By this year that number has trickled to fewer than a dozen. This past academic year, all of our 800 or so incoming students who accepted offers of admission, and could identify funding resources, arrived by registration day. No one was denied a student visa. The oft-discussed “visa problem” for international students is not a significant issue at MIT. Our students get their visas. And the vast majority arrives in a timely fashion.

So what’s to worry?

There is growing anecdotal evidence that while our international student population is, by and large, very happy at MIT, they are ambivalent about being in the United States. Many of our students report a distinct feeling of unease about the political and cultural climate in the U.S.

That unease surrounds their stay at MIT, as they come to understand just how extensively their activities and whereabouts are tracked and recorded by federal authorities; and as their motives for studying in the U.S. are questioned by those authorities. Our students are keenly attuned to an atmospheric shift in the American environment, one tilted toward suspicion of foreign nationals, and in the extreme, even menace. Why, we hear some international students asking themselves, should we commit to this less-than-fully welcoming environment?

Once in the U.S., it is relatively easy for an international student to run afoul of immigration laws. If you pass your qualifiers, but forget to apply for a new immigration document which reflects the higher degree, or if you move and fail to update your address within 10 days, or if you allow your documents to expire by as little as one day, your legal status in the U.S. will be “terminated.” Such oversights, though often redeemable through a lengthy and costly reinstatement process, can potentially plague a student throughout a career in the U.S. The record of the “mistake” never goes away. You will likely be asked about it in future applications.

| Back to top |

The Student Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) is the government’s student tracking database. It is often inaccurate and chronically out of date. It is also unforgiving. A few examples:

- A returning African student was told at a U.S. Embassy that his status in SEVIS was “deactivated” and he was no longer entitled to a student visa. In fact, though the student had been a graduate student for nearly a year, it was his undergraduate record that the Consular Official had accessed. Urgent faxes and e-mails from MIT, even a copy of the active record in SEVIS itself, would not dissuade this particular consular official. The SEVIS record he could see was all that mattered.

- A PhD student was stopped during a random security check in upstate New York. After a cursory check in SEVIS, the border official bluntly told her that she was in the U.S. illegally, and promptly arrested her, holding her in a makeshift cell for several hours. Her young friend and boyfriend were witness to the events, were shocked and frightened, and won’t forget it any time soon. A year earlier the student had withdrawn from MIT for a term and departed the U.S. to care for an ill parent. The authorized withdrawal was duly noted in SEVIS, as was the fresh entry to the U.S. when the student returned to full-time registration. According to the student, the agent simply didn’t believe her and refused to allow her time to secure documentary evidence of her status before placing her directly into deportation proceedings. She was, in the agent’s view, “unlawfully present in the United States.” When I spoke to the agent a few days later confirming her MIT status, he told me over the phone that “she didn’t look like a PhD student at MIT.”

- A pregnant PhD student was re-entering the U.S. after a visit home. While the border official acknowledged that her SEVIS records were in order, he proceeded to aggressively question her about her pregnancy, accusing her of “using her student status” to ensure that her baby was born in the U.S. This demeaning encounter left our student so shaken that it was weeks before she could speak about the experience without sobbing.

Of course, cases such as these get eventually “resolved.” The beleaguered student arrives back at MIT and returns to his or her research. The anger and hurt retreats. But the experience leaves a sting, not easily forgotten. And of course these stories have legs. They are told and retold to other students, to anxious faculty and staff, and to family back home.

Unwelcoming and disconcerting experiences such as these are having a perceptible impact on our students. Some are beginning to openly question whether or not they want to pursue education, careers, or lives in the U.S. They are increasingly considering internships, research and employment opportunities outside of the U.S. “. . . to hedge my bets,” as one student put it to me, “in case I find I don’t like it here.” Recently, three different students married to U.S. citizens have indicated that they have no desire to pursue opportunities in the U.S. after graduation. One of them, a Russian national, said he had no intention of ever applying for a green card. Another, a PRC national, is going off with her husband to a post-doctoral position in Finland after graduation. This kind of rejection of even considering opportunities in the U.S. was unthinkable as little as three years ago.

Should we be concerned that foreign students feel less welcomed and at ease in a security-minded America? Other countries have always coveted our highly talented students, and our students have always had choices. But now competing countries have more to offer than in the past.

With stronger economies, aggressive global recruitment strategies, and enhanced academic and research infrastructure in places such as Canada, India, China, and much of Asia, “our” students are actively wooed.

These countries are also pointedly liberalizing their visa polices as U.S. immigration policy becomes more prohibitive. Friendly immigration policies in Canada, the UK, and Australia specifically target scientists and engineers. Other countries will no doubt follow suit. The message implicit in these polices resonates deeply with MIT’s international students: “We want you. We will value you when you are here.”

Why wouldn’t our students begin to respond to this welcome?

Wouldn’t you?

MIT provides an extraordinary and effective environment for research and education to all of our students, including our internationals. Within MIT, international students feel valued and vital to this vibrant academic community. Many will build lasting relationships with the Institute, and many with the United States. But we cannot ignore the troubling implications of the broader American environment to the well being of our community.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |