| Vol.

XXV No.

2 November / December 2012 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Graduate Student Life, Research Productivity, and the MITIMCo Proposal

The value of a residential campus

Few faculty, students, or administrators doubt the advantage of a residential campus over a commuter campus for undergraduate education. The ability of students-in-residence to continuously interact with each other, with their TAs, with grad students and faculty in UROP projects, provides a deeply enriched educational environment, compared to a dispersed commuting campus. This is even truer for graduate students. Particularly for those graduate students whose theses require hands-on work (e.g., in biology, chemistry, chemical engineering, and many other experimental disciplines), the interaction of students with each other, with postdoctoral fellows and research technicians, is absolutely critical for optimal research productivity. In addition, many graduate students have to be able to spend extended and irregular time with their experiments, unrelated to the rhythms of the conventional workday.

The MIT 2030 Task Force report notes the absence of housing needs or goals in the MIT 2030 plan, and calls for a study of housing needs of MIT graduate students, faculty and staff.

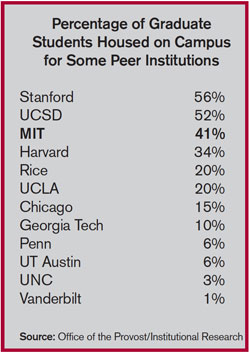

The table shows that many leading research universities house a significant fraction of their graduate students on campus. For some strong research universities, low graduate student residence numbers are misleading, as the campuses are surrounded by residential neighborhoods providing graduate student housing adjacent to campus. Though there are few studies on the relationship between graduate student residences and research productivity, there are very few full commuter campuses in the top tier of research universities.

The graduate student housing dilemma

With limited on-campus graduate housing, more than half of MIT graduate students have to secure housing off campus. Unfortunately, the increased cost of housing in Cambridge is causing considerable distress for our graduate students. As described in the May/June’s issue of this Newsletter ["Concerns Over the Lack of Graduate Student Housing in the MIT 2030 Plan"], vacancy rates in Cambridge are around 1%, among the lowest in the nation. Given the commercial development in Cambridge, housing costs are very high and increasing significantly faster than graduate student stipends. Graduate students cannot compete financially with employees of Novartis, Shire, Pfizer, Microsoft, or Google.

One consequence of this is that our students are being pushed further away from the campus, resulting in an ever increasing time spent commuting, and significantly decreasing their productive time on campus. In practice, many students are limited to housing that is near the Red Line or other public transit, with attendant higher rents.

Furthermore, as many faculty know, commuting by car into and out of Cambridge, across the BU Bridge, through the Alewife Brook interchange, on McGrath Highway, or through Union Square, meets with increasing congestion. If the proposed developments in Kendall Square, Central Square, Alewife Brook, and North Point – on the order of 18,000,000 square feet – are built, the number of auto trips/day into and out of Cambridge will increase by more than 50,000, with a similar increase in Red Line and bus trips. Given that the Red Line is already close to saturation point, and the critical road interchanges are already heavily congested, commuting to and from MIT is going to be more and more time consuming. Thus it is not practical for graduate students who have to spend considerable time with their experiments to try to lower their rents by living outside of Cambridge.

The solution is campus graduate student housing

The solution – just as for undergraduates – is to build sufficient housing on the campus. Many of our nation’s leading research universities have followed this path.

President Vest’s administration listened to the housing concerns of graduate students [see: MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. 13 No. 2, “Pressing Issues for Graduate Students”] and launched an effort to increase on-campus graduate student housing to 50% of the need. This resulted in the renovation of 224 Albany Street into graduate housing and the construction of the Pacific Street housing. That was an important step in the right direction, but the initiative was not sustained under President Hockfield. That path should be pursued by building additional graduate housing. Campus space to the northwest between Mass. Ave. and Main St. has already been leased for 40- and 60-year periods to Pfizer and Novartis. That leaves the MIT land between Main Street and Memorial Drive on the East Campus as the most natural area for new construction of graduate residences.

The MITIMCo proposal ignores graduate student housing needs and its relation to research productivity

Unfortunately, MIT 2030 and the MITIMCo up-zoning proposal ignore this need. In particular, the MITIMCo proposal focuses on building commercial offices on campus land, which will be leased for long terms as a source of income. No student housing has been included in any of the MITIMCo presentations to the Cambridge Planning Board. This lack of housing was sharply criticized at the Planning Board hearing by both representatives of the East Cambridge and Kendall Square communities, and by MIT’s Graduate Student Council.

It is perhaps not surprising that real estate executives who have driven the MITIMCo proposal would be insensitive to issues like graduate student housing. In addition, there is an intrinsic conflict of interest with MITIMCo’s real estate managers receiving much larger bonuses from long-term commercial leases than from building affordable graduate student housing.

These are among the many reasons MIT needs a standing Campus Planning Committee of faculty, administrators, staff, and students, as suggested by the faculty MIT 2030 Task Force in their closing section.

The MIT 2030 plan focuses on the income generated from the commercial leases. But real estate profits can be realized in many venues in the Boston area, elsewhere in the U.S., and abroad. Graduate student housing is only of use to MIT if it is in on the campus or in close proximity. In addition, a significant fraction of MIT income – overhead on research grants – depends on graduate student productivity. Reducing the quality of life and productivity of a significant fraction of MIT’s graduate students has real costs, even though they may not be easy to assess. At a minimum, the MITIMCo up-zoning proposal should be put on hold until the Provost’s Task Force on Community Engagement in 2030 Planning has been digested by the faculty and graduate students, and the redesign called for has been assessed and adopted.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |