| Vol.

XXVIII No.

3 January / February 2016 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Constraints on Civilian R&D Budgets

From Excessive Pentagon Spending

In December 2015, Congress adopted its Omnibus Budget Bill, appropriating $1.15 trillion for federal spending in the coming budget year. We can take some comfort that the R&D budget increased by 5%. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget was increased $2 billion to $32 billion, while NASA’s science budget received a 6.6% increase to $5.6 billion, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) budget increased 4.4% to $5.77 billion. In a statement released December 17, 2015, the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) "applauded the high priority that Congress placed on reinvesting in our nation’s innovation system." However, a few sentences later, they stated: "As has been well documented, the United States has fallen behind other nations in the priority it places on R&D, recently ranking 10th among developed nations in R&D investment compared to the size of its economy.” U.S. non-defense R&D has decreased from approximately 0.9% in the 1960s to 0.34% today. [Jeffrey Sachs, The Boston Globe, February 4, 2016.]

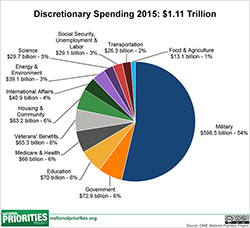

Though the negotiations over the budget were widely reported – mostly devoted to the issue of riders that might or might not be appended to the budget (such as defunding Planned Parenthood) – news accounts were generally silent on the most profound aspect, the overall budget priorities. In fact, more than $600 billion, about 55% of the total Congressional discretionary budget – our tax dollars – was appropriated for Pentagon spending and weapons procurement, including DOE (Department of Energy) nuclear weapons, and the Overseas Contingency Operations Account.

R&D funds are the engine driving scientific and engineering research and higher education in our research universities and medical schools. They provide on the order of $460 million to MIT’s operating budget, about 66% of the total (see ) financing our research equipment, materials and supplies, publications, research assistants, postdoctoral fellows, and general operating overhead. Given their long-term importance, projecting necessary investments in R&D, technological innovation, and higher education, requires carefully assessing the balance between our military and civilian expenditures. We offer examples below indicating that this balance has shifted too far to the military side. We would have a healthier society, stronger economy, and a less dangerous international policy if we reduced the 55% of our discretionary budget going to the Pentagon, in part by spending less on nuclear weapons, and increasing spending on civilian needs and programs.

Despite this year's increases in the R&D budget, we are still underinvesting in civilian research. Following are just three examples of some of the many critical investments needed for national health, for public transit, and for dealing with climate change.

Biomedical Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases

The $32 billion for biomedical research financed by the National Institutes of Health in universities and hospitals across the country will be about 3% of the federal budget under the control of the Congress. At this time, neurodegenerative disease affecting the brain (including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s) afflicts more than 4.5 million Americans. By 2050, the numbers for Alzheimer’s alone are expected to triple to 13.2 million. These long-lasting afflictions cause a great emotional and economic cost to the families and to the nation as a whole. The Alzheimer’s Association projects that caring for patients with Alzheimer’s will cost all payers – Medicare, Medicaid, individuals, private insurance and HMOs – $20 trillion over the next 40 years.

As a result of prior NIH research investments, the mechanisms of diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s are reasonably well understood. The key proteins have been identified, as have many steps in the development of pathology. Thus the time is ripe for the development of effective anti-Alzheimer’s drugs, with many pharmaceutical firms pursuing vigorous programs. However, development of effective therapies requires human trials testing for improvement in cognition and behavior, and looking closely for side effects, particularly in higher brain functions. These trials are enormously expensive.

Given the known and increasing cost to the nation as the population continues to age, the rational approach would be an all-out effort – like the moon landing program in the 1960s – by sharply increasing the federal R&D budget for neurodegenerative diseases. Senator Elizabeth Warren has called for supplementing the NIH budget with fees from the pharmaceutical industry, but this is only a small step in the needed direction. In his State of the Union address, President Obama called for new efforts toward cancer therapies. Subsequent reports indicated a sum of ~$1 billion, a step in the right direction but hardly a “moonshot.”

What our nation needs is on the order of a 10x increase in neurodegenerative R&D to $10 billion a year. This would still leave the total NIH R&D budget at only 4% of the total. Yet a majority of the members of Congress claim that the nation can’t afford such expenditures. Nonetheless, they voted some $30 billion for upgrading nuclear weapons capacity, both unnecessary and destabilizing, and counter to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty that the U.S. ratified 40 years ago.

Public Transportation

On May 12 last year, an Amtrak train derailed outside Philadelphia, in part because of the failure to install Positive Velocity Control (PVC) signals. The next day, a Senate committee supported a further reduction in Amtrak investment. The sums under discussion were in the $1-2 billion range. Subsequently, the Republicans in the House passed a transportation bill reducing Amtrak funding by $250 million below the President’s $2.45 billion request. Delays and equipment failures on the Massachusetts MBTA, and on New Jersey Transit, stranded or delayed tens of thousands of rail passengers, causing serious personal inconvenience and cost, as well as overall damage to the economy. The derailment represents failure to upgrade track bed, rail cars, and signals, and failure to install PVC technology throughout the route. According to Amtrak, the New Jersey Transit delays “. . . stem from long-term under-investment in the Northeast Corridor.” New York and New Jersey have recently agreed on the need to upgrade the rail corridor, including the building of two new tunnels under the Hudson River, but the source of the funding is unclear.

From a broader perspective, these failures reflect the almost insignificant investment by the Department of Transportation in R&D on sensors, signal systems, and telecommunications needed, not only to bring both passenger and freight trains up to the already obsolete twentieth-century standard, but to prepare for higher speed, more efficient passenger travel that will be needed later in this century if the U.S. economy is to continue to grow.

After many years of stopgap single-year funding, Congress passed the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. This act authorizes a total of $305 billion over the next five years, with $10 billion spread over five years for passenger rail improvements. These sums are totally inadequate to the need, and are dwarfed by European and Asian investment in rapid and energy-efficient rail transit.

Though the nation apparently can’t afford to improve the safety and efficiency of train travel for hundreds of thousands of Americans, we can afford to spend billions of dollars each year increasing the accuracy of our nuclear missiles. The Draper Lab in Cambridge received $2.7 billion in DOE contracts to increase the accuracy of nuclear missiles. Given warheads that will obliterate every living creature within miles of the explosion, increasing accuracy from 600 meters to 300 meters is deeply absurd and a terrible waste of national resources.

Meanwhile, the Department of Transportation Volpe National Research Center two blocks away is sufficiently strapped for funds that they are negotiating to sell some of their land to a commercial developer in exchange for building renovations.

Sustainable Energy

Committees of the National Academy of Sciences, the United Nations, and many professional organizations agree that the Earth’s climate is heating up, putting many sectors of human society at increased risk from multiple factors: rising sea levels increasing weather extremes – both storms and droughts – and changing fresh water hydrology and availability. There have been many calls for intensified R&D into sustainable energy, and many states have established incentive programs. But real progress requires large-scale scientific and energy efforts. Yet the Department of Energy budget for research development and demonstration remains under $5 billion, no higher than it was five years ago. In fact, the DOE spends far more on nuclear weapons maintenance and upgrades than they do on sustainable energy research. Similarly, the NOAA budget provides only $58 million for climate research instead of the requested $89 million, and $10 million for ocean acidification research rather than the requested increase to $30 million.

Although Congress routinely separates spending bills into civilian and military categories, the only way that ~$600 billion for military spending can be appropriated is to limit civilian programs, as has been done over the past decade, or to increase taxes (which has become politically taboo). The Congressional Budget Office projects the cost of U.S. nuclear forces for the decade 2015-2024 at $348 billion. A significant fraction of that cost is in replacement of our land- and sea-based intercontinental missiles, a cost which will increase in the following decade.

| Back to top |

Excessive Nuclear Weapons Spending

One arm of our current nuclear weapons triad is the U.S. fleet of 14 nuclear powered and nuclear-armed submarines, the world’s largest. Each submarine carries multiple warhead missiles, representing a several orders of magnitude greater destructive power than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In addition to the blast, heat, and radiation damage, launching and detonation of the Trident missiles from a single nuclear weapons submarine – either by accident or intent – could be sufficient to induce a “nuclear winter” leading to worldwide famine, resulting in the deaths of tens of millions of people. The current Pentagon proposal, a quarter-of-a-century after the collapse of the Soviet Union, proposes buying eight new nuclear weapon submarines at $12 billion each.

Sadly, the President’s State of the Union address included no mention of the need to reduce our nuclear weapons stockpile, retreating from his earlier 2009 call in Prague to rid the world of nuclear weapons.

These projected expenses are a classic example of “less would be more”; they are not only economically counterproductive, but ironically they also decrease our national security. Steady improvements in the accuracy of our ballistic missiles increases Russian fear of our first-strike capabilities (no matter how implausibly we view this as a possibility) and coupled with their less robust early warning system, could possibly lead to an accidental launch which would start a nuclear war. The probability of this “doomsday scenario” is low, but not zero, as massive failures of complex technical systems have occurred – e.g., Challenger, Fukishima. Indeed, twice false attacks have been indicated on Russian early warning systems, a response having been averted only by the heroism of individual officers who were on duty.

Our systematic nuclear weapons and delivery system improvements feed the dangerous international competition for the modernization of nuclear weapons in Russia and China, making it more difficult to negotiate arms control agreements. They play into other countries’ notions of the importance of nuclear weapons (e.g., India, Pakistan, North Korea), which is very dangerous for international stability.

We note sadly that despite our having almost a thousand nuclear weapons on hair trigger alert and capable of pinpoint accuracy, this has not prevented North Korea from proceeding with their nuclear weapons program. The path to security is nuclear reductions, not increases.

Our reliance on nuclear weapons helps to undermine the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that is a cornerstone of our security, as exemplified by the recent intense negotiations with Iran. The NPT depends on an agreement that the countries that forgo nuclear weapons are entitled to develop nuclear power and expect the nuclear powers to disarm (NPT Article 6) although the time scale is not defined. The failure of the 2015 NPT review at the UN to reach a consensus this past June was due in large part to the failure of the nuclear weapons states to define any specific procedures or time scales to divest their nuclear weapons.

Given that the current U.S. nuclear arsenal represents extraordinary overkill capacity, there is no increase in national security to be derived from increasing its destructive power. In 2012, a committee chaired by former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General James Cartwright, concluded that: “No sensible argument has been put forward for using nuclear weapons to solve any of the major 21st century problems we face including threats posed by rogue states, failed states, proliferation, regional conflicts, terrorism, cyber warfare, organized crime, drug trafficking, conflict-driven mass migration of refugees, epidemics, or climate change…. Nuclear weapons have…become more a part of the problem than any solution.”

We conclude that a major reason behind the shortfall in civilian R&D is diversion of federal tax dollars to the continuing excessive, wasteful, and dangerous spending on new and upgraded weapons systems, including destabilizing nuclear weapons, which dwarf civilian investments. Continuing investment in such non-productive and provocative weapons programs will result in a declining standard of living and quality of life. As President Eisenhower warned us, in the long term undermining of the civilian economy only decreases our national security.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |