| Vol.

XXVIII No.

4 March / April 2016 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

MIT Engineering Systems Division R. I. P.

Eulogy for a successful experiment 1998-2015

On July 1, 2015, the Engineering Systems Division (ESD) ceased to exist as a recognized organizational unit at MIT. This event went unnoticed perhaps by a majority of the MIT community, but for those of us who were an integral part of the life of the Division it was a major event. Not much has been said or written by either the administration or former members of ESD since then, and so I felt compelled to write this article. This piece is not an official history of ESD, but simply a personal reflection, since the Division has played a major role in my own career and also in that of several of my colleagues here at MIT. I will first review the creation of ESD and its early trajectory (1998-2004), followed by its most active period (2004-2011) and its ultimate decline and discontinuation (2012-2015). I will also attempt to extract some lessons learned from this experiment, both for me personally, and for MIT as an institution.

Creation of ESD – Need for “Big E” Engineering (1998-2004)

The MIT Engineering Systems Division was founded on December 1, 1998 under then Dean of Engineering Bob Brown. This event followed on the heels of a multi-decadal effort to create a new unit at MIT that would focus on the science and engineering of large and complex socio-technical systems. Examples of such systems include global manufacturing and supply chains, multi-modal transportation systems, electrical power generation and distribution networks, and health care systems. The particular impetus for the creation of ESD came from a report of the Eager Committee, named for Prof. Tom Eager who was then Department Head of Materials Science and Engineering, and who chaired this visionary committee that included, among others, Institute Professor and later Dean of Engineering Thomas Magnanti. The group issued its recommendations in 1996 [T.W. Eager (chair), D.A. Lauffenburger, T.L. Magnanti, E.M. Murman, D. Roos, “Final Report of the Committee on Hiring and Promotion of Faculty interested in Big E Engineering,” MIT School of Engineering, September 15, 1996] and included the following statement:

“In order to expand MIT’s activities in engineering systems and engineering integration, we propose that the School of Engineering create a Division of Engineering Systems that cuts across the eight Engineering Departments. This Division would report to an Associate Dean, would have a faculty rank list and budget, with the authority to develop curricula, admit students and hire and promote faculty.”

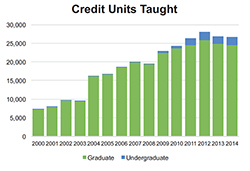

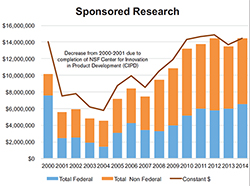

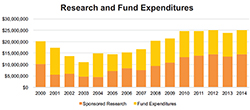

Prof. Dan Roos became ESD’s founding director and Associate Dean of Engineering Systems in 1998 and served in that role until 2003. He was followed by Prof. Daniel Hastings (2003-2005), Institute Prof. Joel Moses (acting, 2005-2007), Prof. Yossi Sheffi (2008-2011), Prof. Joseph Sussman (interim, 2011-2012), Prof. Steve Graves (interim, 2012-2013) and Prof. Munther Dahleh (2013-2015). The evolution of ESD during its first decade was characterized by a pioneering spirit that included the creation of a new PhD program in Engineering Systems, the placement within ESD of several pre-existing Masters programs including TPP, LGO (formerly LFM), SDM, and SCM (formerly MLOG) and the organization of several workshops that led to some seminal intellectual cross-pollination amongst the roughly 50 faculty members associated with ESD. Several inset graphics accompanying this article show the evolution of ESD over time, for example in terms of the number of credit units taken by MIT students in ESD subjects, indicating a growing interest in this area.

(click on image to enlarge)

(click on image to enlarge)

(click on image to enlarge)

With the formation of ESD came a commitment to hire eight new junior faculty members as so-called “duals” between ESD and a department in the School of Engineering. The idea that an interdisciplinary unit like ESD would have half-faculty slots – to be used in conjunction with half-slots from the departments – was unique. Faculty from other departments and programs at MIT joined ESD, including those from the Sloan School of Management, the program for Science, Technology and Society (STS), and others.

Some were duals and others were the more traditional joint faculty. I was fortunate enough to be offered one of the first “dual” slots between ESD and the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 2001, a perfect fit for my research interests at the intersection of aerospace systems, engineering design, and strategy.

The year 2004 essentially completed the startup phase of the Division with an international Engineering Systems Symposium held at MIT, a report issued by the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) regarding the envisioned characteristics of Engineers in 2020 [The Engineer of 2020: Visions of Engineering in the New Century, National Academy of Engineering, ISBN: 0-309-53065-2, 118 pages, 6 x 9, (2004)], as well as the completion of an initial five-year review – required by MIT for any newly-formed unit – by an independent faculty committee led by Prof. Ahmed Ghoniem [A. Ghoniem (chair), H.F. Hemond, G. McRae, S. Silbey, T. Stoker, N.E. Todreas, ESD Five Year Review Committee, Final Report, September 2005]. Even though ESD passed this initial review, there were several recommendations and some criticisms expressed in the report that would never completely vanish in the following decade, despite ESD’s efforts to address the recommendations and its manifest growth and intellectual progress. At the time some of the criticisms seemed to me to be legitimate and not unusual for a relatively young academic unit. While this led to some consternation within ESD, the above mentioned NAE report provided confirmation that ESD was indeed on the right path.

(click on image to enlarge)

(click on image to enlarge)

| Back to top |

The “Golden Age” of ESD (2005-2011)

During the period between roughly 2005-2011 ESD continued to grow and gain increasing traction in fulfilling its mission. This seems to me to have been the “Golden Age” of ESD and some of the accomplishments during this time are summarized here:

- Pre-existing programs such as TPP, TMP, SDM, LGO (LFM) and SCM (MLOG) were managed under a more integrated and joint umbrella, with each retaining a relative degree of autonomy. This gave a general sense that these interdisciplinary programs had a common home at MIT.

- Following a retreat in 2001, the ESD faculty voted to initiate a new PhD program in Engineering Systems, incorporating the prior Technology, Management and Policy (TMP) program. The first cohort graduated in 2005.

- A number of junior faculty were hired and promoted over these years, with mixed results. While some junior faculty, including myself, felt very much at home in the Division, others decided to change their appointments from dual to joint or leave the Division altogether because they felt that working in a more department-centric structure would work better for them. The promotion and tenure process for dual junior faculty was also challenging since they had to effectively convince both ESD and their other department that they satisfied the criteria for tenure at MIT.

- As ESD’s intellectual agenda matured and scholarship in Engineering Systems progressed, the MIT Press decided to create a new book series in the field. This series was successfully launched in 2010 and has since published five titles, including an overview about Engineering Systems as well as books on methods (e.g., the Design Structure Matrix) as well as on designing systems for lifecycle properties such as flexibility and safety. A more recent book looks at complexity in health care systems.

- MIT’s activities in the area of Engineering Systems did not go unnoticed at other universities. In 2004, the Council of Engineering Systems Universities was created with like-minded programs around the world. It is fair to say that ESD served as the catalyst for the formation of CESUN. This organization continues to this day with about 60 university members and bi-annual conferences and annual meetings. The 2016 meeting will be hosted by George Washington University (GWU) in June. A number of programs were created in direct response to MIT’s foray into this new area.

- U.S. News and World Report expanded its graduate rankings of engineering programs in 2013 to broaden the existing category of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering to include Systems. The ESD program was ranked third nationally in 2013, the first time it was included in this category. I viewed this as a significant success, but it went almost unnoticed by MIT’s administration.

Decline and Discontinuation (2012-2015)

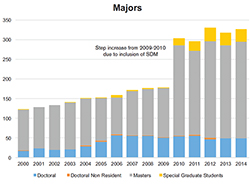

Starting in 2011, it became clear that ESD, although the third largest graduate program in the School of Engineering with about 300 students, and having also gained the right to hire “ESD only” faculty – rather than duals – under then Dean of Engineering Subra Suresh, was at a crossroads. In a number of dimensions, such as the faculty/student ratio, ESD was understaffed and under-resourced. At the same time, ESD’s graduates were increasingly in demand by systems-oriented programs around the world. To most of us in ESD it seemed that the Division was doing well, especially as we saw our program emulated elsewhere around the world, particularly in those universities participating in CESUN.

At this point a change in the leadership of the MIT School of Engineering took place. Dean Suresh, who had been generally supportive of ESD, left MIT to become the director of NSF and was succeeded in February 2011 by Dean Ian Waitz. One of Dean Waitz’s first orders of business was to examine more deeply the future of ESD.

A series of committees and long consultations ensued, which eventually led to the recommendation to disband ESD in its current form and create in its stead a “new entity” following the model of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES). During this difficult period that lasted about four years, the Division was unable to hire new faculty or to continue on its planned growth trajectory. The ESD Visiting Committee met several times during this same period, and was supportive of ESD in its written reports to the Corporation, although this seemed to have little impact. While I feel that a “proper” process was followed in the sense of the recommendations of the Widnall Committee, I could never shake the impression that, beginning in 2011, the discontinuation of ESD was a foregone conclusion.

The main reason stated or implied for ESD’s discontinuation as a unit were alleged “quality issues” in its programs, as well as an unwillingness by the School of Engineering to further support it. I have to this day not seen any concrete evidence or data that supports the allegations of “quality issues” associated with ESD. As is so often true in life, perception is reality. However, this perception seemed to have been mainly an internal MIT issue, since as stated earlier the ESD model was being copied or emulated at other universities. My own hypothesis is that the main reason for ESD’s discontinuation was that its ambition to conduct “unified” research that would meld together engineering, management, and the social sciences in a way that would make the disciplinary boundaries between these fields nearly indistinguishable, caused a counter-reaction by more disciplinary-oriented faculty and some administrators. Similar tensions are often observed in the painful birth of new research fields and disciplines, as they are in the study of socio-technical systems.

Lessons and Takeaways

As a result of ESD’s discontinuation, MIT launched a new unit as of July 1, 2015 – the Institute for Data, Systems and Society (IDSS) – under the able leadership of Prof. Munther Dahleh. The mission of IDSS is quite similar and yet somewhat different from the earlier conception of ESD. IDSS is focused on the increasingly large amounts of data that are generated by today’s complex systems and how these data can be statistically analyzed and ultimately lead to better models and decisions. The core faculty in IDSS is centered around the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems (LIDS), some remnants of ESD, and other faculty at MIT across all five Schools. The research in IDSS has a distinctly more mathematical, almost “algorithmic” flavor, and I have to admit that I do not yet feel the same intellectual resonance in IDSS as I felt in ESD. Nevertheless, I am willing to give it a try and be a positive contributor to the future of IDSS, even though the loss of ESD is still painful to me.

As we look back at the 17-year history of ESD at MIT there are several lessons learned that stand out for me:

- Initial conditions matter. While ESD was created in 1998 under then Dean Bob Brown, the level of enthusiasm for the new unit was only moderate and the migration of faculty into the new unit from CEE, Aero Astro, and other units ruffled some feathers. A potential contributor to this was the lack of explicit backfill for the dozen or so faculty members who moved their full or half appointments to ESD. To be successful, a new interdisciplinary unit should have more universal support at all levels and receive a strong initial commitment and endowment. In that respect, it is probably true that IDSS’s initial conditions in 2015 were stronger than those of ESD in 1998.

- Continuity of leadership. ESD has had a number of very capable and respected directors (mentioned above) during its existence. However, many of these were only “acting” or “interim” and every leadership change created a discontinuity. In sharp contrast stands the Biological Engineering Division (BED) that became the successful Department of Biological Engineering under the sustained and strong leadership of Prof. Doug Lauffenburger. In order to reach its full potential a new academic unit should be led by the same person for at least the first decade of its existence.

- Clarity of mission. The mission of ESD was a bit fuzzy from the start. For some the ambition was to “broaden engineering” by simply supporting the departments and by creating a common home for the various systems-oriented programs at MIT. For others it was a more ambitious quest for a unifying theory underlying all socio-technical systems, an attempt not dissimilar to the General Systems Theory of the 1950s and ’60s [Von Bertalanffy, Ludwig, and Anatol Rapoport, eds. General Systems. Society for general systems research, 1963]. Over time ESD’s agenda became more ambitious, swinging towards the latter view, as did the amount of resistance by some at MIT. It is also true that as ESD’s activities expanded, the needed resources in terms of faculty, space, and budget did not.

- Unified versus federated approach to socio-technical systems research. A unified approach aims to not only bridge established disciplines but to formulate a new ontology that incorporates and harmonizes research in previously separate disciplines or fields. This was more or less ESD’s approach. A federated approach is where recognized experts in different disciplines (e.g., engineering science, policy, economics . . .) get together to tackle a specific problem or question using the theories, methods, and tools that are well accepted in their home disciplines. After their joint effort is done, they disband again to retreat to their home turf. This is how many policy studies on key societal topics such as energy, manufacturing, the environment, and innovation are done. In my view, there is a need for both approaches. The risk of the first is that the research is, or is perceived as, shallow if the unified approach is reduced to the least common denominator of the participating disciplines. The danger of the second approach is that a common approach and lasting scientific advancements are never achieved due to the more ephemeral nature of the collaboration.

In summary, it is my view that ESD, in the period from 1998 to 2015, has in many ways been a successful experiment. It significantly advanced research in socio-technical systems at MIT and beyond. It strengthened a number of educational programs; and it created an open and inviting research environment. Others may argue that ESD failed because it did not permanently inscribe itself as an organizational unit at MIT. While the memory of ESD will likely fade over time, the intellectual contributions, exceptional graduates, and worldwide community interested in tackling socio-technical problems in a unified way will live on. For MIT, the ESD experience should serve as an opportunity to learn and become more reflective in terms of the drivers of its own organizational transformation. But that is a topic for another day.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |