South Station / Dewey Square

Time

The above map viewer allows you to explore the development of the Dewey Square area through Sanborn Atlases from 8 different times. Drag to pan; Scroll to zoom; Click top right button to switch map year.When walking in between the enormous skyscrapers of any American city's downtown, one might feel surrounded by a solid, static environment. The previous essay on natural processes already gave some reasons why this turns out not to be true: the city is in continuous plastic change due to the interaction with nature that is at all times in and around it. This essay now, will explore how we, as mankind ourselves, influence and change our urban environment over time. Much in the way nature influences the city in the broadest range of scales imaginable, from a single settling curb attracting all bikers to follow a certain path, to the entire climate determining what building techniques are employed, our own decisions also change cities on both a very local and an overarching scale. A single investor with an idea for a project can drastically change how one square or street functions, while a city planning might decide on how that same cities inhabitants move around.

What is important to realize is that a local decision by a single investor or house owner can also influence the city on a much larger scale. Societal values of a certain time, like the desire of the wealthy to move to quiet suburban communities in the nineteenth century, might influence a large amount of single investors in their decisions, thus emerging a pattern of change on a scale reaching beyond the individual. In this essay, I will try to explore and explain these patters of change for the site I have selected for this project, the Dewey Square and South Station area.

Dewey Square itself fulfills so many diverse functions in the city that it becomes hard to decide where to look. Today it is probably the most active transportation hub in Boston, linking together Amtrak service through south station, national and international buses through the bus terminal, and local transport though the MBTA red- and silver line connections. But it is also part of the city's important business or financial district, shaping the surroundings with humongous skyscrapers and filling the square with businessmen in suit and tie in a hurry to make that important meeting. Then there are also all the commuters walking around, providing a perfect location for commerce to settle – and that is only looking at the snapshot of the area that we see today, all the functions this very same space fulfilled in past decades. What changes exactly where most influential? Was it the dock that has been around since the very first settlements in Boston, the resulting availability of cargo that drew industries here? Was it the technological advancements enabling elevated railway service, the railway terminal in the first place, and the subway? Was it the automobile and how it changed the way people did business? Was it the recent introduction of the Greenway that makes this a pleasant area to be around?

While working on this essay, I've come to realize that only the continuous interaction of these changes provides an answer to why Dewey square changed the way it did. I will elaborate on a few patterns of change that I think have been important, but want to invite you to look at the same sources I used and see what you might discovered. I based most of my observation of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Atlases from 1867, 1885, 1909, 1929, 1958, 1974, 1981 and 1992. I assembled eight maps from those sources, all of which are available through the map viewer above.

Considering how important transportation has been for the development of Dewey square, I will structure findings about social and environmental change around the introduction and disappearance of methods of transportation.

The port and its surroundings

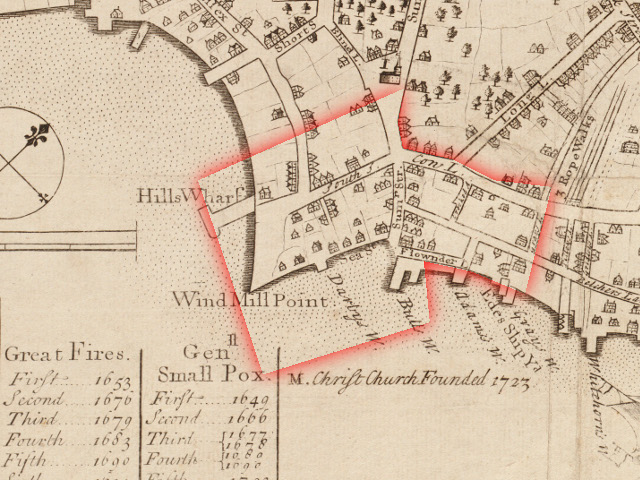

As explained in the essay on Natural Processes, what is now Dewey Square finds it origins as a port. Transportation over land involving horse drawn carriages or walking was tedious and slow. Supplies reached the New World over water, and in this context Boston proved the perfect location for a settlement. At this very location, one could find the waterfront up until the end of the nineteenth century. The presence of wharves and, because of them, the availability of resources attracted various industries. The 1867 map shows a variety of factories throughout the area: coffin factories, furniture factories, distilleries to name a few.

Boston Public Library, Leventhal Map Center

Another interesting thing is that South Station's root as a transportation hub can even be found here: it turns out that the “Liveries” [] that are mentioned on the 1867 Sanborn map are in fact stables with horses and carriages available for rental, which suggests that this location had a significant amount of incoming people that needed transportation away from the area even at that time.

The more detailed map from 1885 then shows an overwhelming peak of this industrial activity: nearly every single building visible is either a factory or a warehouse of sorts. The leather industry clearly dominates – which explains why up to this date, this part of Boston is called the Leather District.

From goods to people, industry to commerce

Yet there are more important changes going on around this time. The industry that originated here due to the availability of waterways introduced a new important form of transportation. The earlier docks and wharves, that already functioned to send and receive cargo, where gradually filled in to make room for more railroad platforms. Exactly parallel to the incoming ships, in between the old wharves, we now find an ever expanding range of incoming railroad platforms surrounded by coal yards and elevators, junkyards, warehouses and the like. Centrally placed, in what appears to be an extension of Summer street, we find a hint to the future of transportation from and to Dewey Square: a passenger terminal, connected to a streetcar on the newly created Atlantic Avenue, where the much narrower Broad Street used to be.

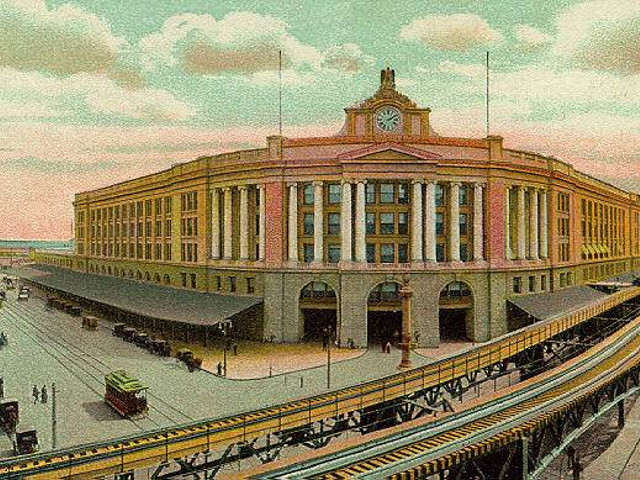

The next map, from 1909, shows the drastic evolution from this new form of transportation that was introduced only half a century ago. The chaos of privately owned, incoming railways and into Boston and their terminals drove Boston officials to find a centralized solution. South Station was the answer to this dilemma. The earlier New York and New England Rail Road Corportation's terminal and all the heavily industrialized wharves south of it where cleared, filled in and replaced by one overwhelmingly huge structure, of only a small part remains today. The terminal had twenty-eight incoming parallel tracks with platform, and was surrounded by lobbies, restaurants and offices.

But what does this technological development tell us about the emerging patterns of repurposing downtown area? Can we recognize a changing mentality? Important to realize is that the introduction of South Station is not just an expansion of the growing railway terminal. Its drastic introduction changed the function of the area it is built on from an industrial cargo railroad yard, filled with junk yards and coal sheds, to an impressive and equally expensive passenger oriented railroad terminal, entirely built in a neo-classical style as was popular at that time.

The 1909 map still shows abundant industrial activity surrounding South Station – but shows the precursors to its complete disappearance. The first large stores start to develop along the new Atlantic Avenue, and the lack of supply for all the industry around the area can only mean that it has to disappear at some point.

This development has to be put in context with societal values of the cities' inhabitants around the turn of the century. The same forces so extensively described by Kenneth T. Jackson in Crabgrass Frontier, that initially drove the wealthy to the quieter surroundings of the city, with the masses in their footsteps, that changed peoples opinions and habits in the city downtown itself. The continuously expanding industry of the nineteenth century had turned the downtown area into a filthy, polluted, noisy and unpleasant place to be around. The separation of industrial and residential area that is so obvious to us today, was not present at that time. In an attempt to transform the city, the focus of new development projects was passengers, not even more expansion of the omnipresent industry – south station is one of the best examples of this.

It is around the same time that South Station developed into the connecting transportation hub that it is today. In 1901, the Atlantic Avenue Elevated Railway was introduced, above the existing street cars, connecting South Station with State Street, the North end and Charlestown. What is known today as the Boston Red Line subway was extended from “Downtown Crossing” to south station in 1913.

Station on a Postcard,

bostonpreservation.org

From people to automobiles

The development that promised to turn dewey square and south station into an active, people-oriented square was put to a halt by the next major technological development that changed how people moved in the first half of the twentieth century in both the United States and Europe. The 1929 Sanborn map shows the first infrastructure this demanding new form of transportation would require. The U.S. Rubber Corportation replaces new stores introduced along Atlantic Avenue earlier. Vacant lots start turning into parking lots; the disappearing industry between South and Lincoln streets is replaced by more “auto parking”.

The complete dominance of Automobile in our urban environment and its development projects culminates in the introduction of the J. F. Fitzgerald Expressway, visible on the 1958 map. Introduced to solve traffic congestion in the Boston area, the elevated highway called the “central artery” cut through Boston's entire downtown. Too narrow even at the time it was build, it would soon be called the “longest parking lot in the world” by Boston citizens.

dominated by the expressway,

source unknown.

The shift to automobile transportation lead to three major changes for Dewey Square. First of all, there is the presence of the expressway itself. Its noise and pollutants must have inevitably changed the way people behaved in the area. Second, the accessibility the expressway provided was desirable for businesses. This made Dewey Square an attractive location for developing skyscrapers, causing the site to become part of Boston's vibrant financial district of the course of the following three decades after the introduction of the Expressway in the 1950's. By 1974 we can see the Stone and Webster office Building between Summer and Congress Street, the older buildings around the expressway are demolished. A third and equally important development is the shift away from rail transport. The streetcars are gone, the Atlantic Avenue Elevated is gone, and the South Station railway terminal largely demolished and repurposed after the two railroad companies serving it went bankrupt because their passengers disappeared. South Station wouldn't regain its functionality as a railway terminal until its renovation in 1989.

From automobile to open space and more...

Automobiles are still our primary form of transportation today, but the way they blend in with the urban environment has been changed drastically. In general, projects since 2000 have been working towards a more habitable environment. The Rose Kennedy Greenway, completed as part of the Big Project, turned what used to be one of the biggest scars in Boston into a breathing park space, again opening room for the community. It is harder to observe patters in the present then to discover them by retrospectively analyzing the past. I personally find the evolution of Dewey Square a positive one, leading towards a more enjoyable urban environment and more sustainable methods of transportation. The community aspect is again visible, both outside, on Dewey Square, as inside, in the various stores (both chains and local ones) that reside in the South Station lobby. I can only hope that city planners, investors and civilians learn from mistakes from the past, and collaborate to construct a sustainable, enjoyable city of the future.

Bibliography

Sanborn Map Co., Sanborn Fire Insurance Atlases Proquest Digital Sanborn Maps, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Rotch Library (various years).Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier, Suburbanization of the United States, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.