Conflict of Interest

Overview

MIT is a world leader in supporting and encouraging spinout companies and a broad array of other entrepreneurial activities. Its first responsibility, however, is to maintain the integrity of the Institute’s education, research, and teaching missions. Processes that promote full and timely disclosure of potential conflicts of interest are critical to identifying, managing, and eliminating risks for members of the MIT community who are participating in allowable entrepreneurial activities.

In The Engine Working Group on Conflict of Interest, we examined three types of real or perceived conflicts—conflicts of commitment, individual financial conflicts of interest (fCOIs), and organizational conflicts of interest (OCIs).[1] We surveyed the published COI policies of peer institutions across the country to gain an understanding of where MIT stands with respect to the broader policy landscape. We also drafted some initial scenarios that illustrate common problematic activities for MIT researchers, postdoctoral associates, and faculty members, as well as potential COI challenges for postdocs seeking to engage with The Engine.

“At a place like MIT, we need well-thought-out conflict-of-interest guidelines to promote the right environment for launching successful, innovation-based companies.”

— Robert Langer, David H. Koch Institute Professor

Where We Are Today

Current MIT COI policies enable faculty, students, and staff to engage responsibly in entrepreneurial activities on condition that such activities do not compromise their commitment to MIT or the integrity of MIT’s mission. These policies are in line with the published COI policies of most peer institutions.

Existing Processes Strike a Balance

Requirements and procedures for disclosure, review, and management of COI issues (real or perceived) attempt to balance the needs of a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem with MIT’s institutional responsibility to its own community, its sponsors, and its collaborators. MIT has designed its policies to ensure that publishable fundamental research—rather than outside financial interests—drives its activities.

Under the current MIT financial conflict of interest policy and using existing guidelines, MIT faculty members can participate with confidence in a wide range of outside activities that align with their institutional responsibilities. Such activities may include, but are not limited to, consulting, starting companies, and serving on scientific advisory boards. Present policies and practices also promote appropriate use of and access to Institute resources and facilities.

Transparency Is Expected and Encouraged

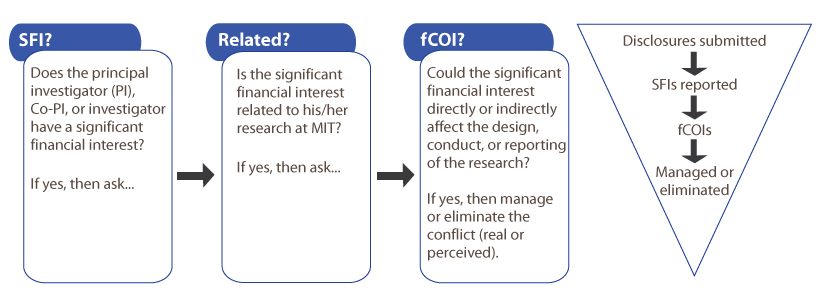

Full and timely disclosure of significant financial interests (SFI) is critical to identifying, managing, and eliminating financial conflicts of interest. This ensures that the design, conduct, and reporting of research funded via grants or cooperative agreements are free from bias that may result from an investigator’s financial conflicts of interest.

Investigators, for example, must describe the business focus of a related entity, their work or role with that entity, and any relationship that business activity may have to their institutional responsibilities. A related entity is an organization in which the investigator, alone or in combination with family, holds a significant financial interest. This level of transparency is particularly important in relations with research sponsors and other collaborators.

Two Processes Protect Individuals

MIT uses two distinct processes to collect and review the information it needs to assess activities that may lead to real or perceived conflicts with the institutional responsibilities of a faculty or staff member, student, or MIT affiliate. The Office of the Provost monitors conflicts of commitment (measured in time) and conflicts of interest via the annual Outside Professional Activities (OPA) report. The Office of the Vice President for Research tracks individual fCOIs—measured in money—that could affect MIT research. The data collected by these two offices indicates that fCOIs often are interconnected with conflict of commitment.

These two processes for disclosure, review, and management combine to protect both the integrity of MIT’s mission and the reputations of MIT and individuals within the MIT community. Identifying and eliminating potential COI issues also remove risks to sponsored research funding (from industry and other sources), compliance with federal fCOI regulations, and MIT IP policies. These processes also preserve the ability of staff members and subordinates to carry out Institute responsibilities free of possible COI. Tracking and reporting protects students and postdoctoral associates and fellows—and their educational and training goals—from being unduly influenced by their own outside financial interests and those of their faculty advisors.

The Engine Structure Mitigates Potential Organizational Conflict of Interest

Because The Engine is organized as a separate corporate entity, its structure mitigates potential OCI for MIT. Only three people who are faculty or employees of MIT are involved in the governing body or operations of The Engine. MIT Executive Vice President Israel Ruiz and School of Engineering Dean Anantha Chandrakasan serve on The Engine’s Board of Directors, and Media Lab Director Joi Ito is a member of the Investment Advisory Committee. Neither the Board of Directors nor the Investment Advisory Committee will make decisions about which companies participate in The Engine. Those decisions, including which companies receive support from The Engine’s investment fund, will be made by The Engine’s officers and other investment professionals who are employed directly by The Engine—not by MIT.

What We Need

The Engine is not restricting its support solely to companies that originate from MIT, license IP from MIT, or are otherwise connected to MIT, and selection criteria will not include a preference for ventures with Institute connections. Nonetheless, MIT enterprises are expected to be among the companies participating in The Engine. Thus, every member of the Institute community must understand MIT’s COI guiding principles and be able to recognize potential conflicts of interest vis-à-vis The Engine.

Endorse Existing Financial Conflict of Interest Principles

By following the Institute’s existing fCOI guiding principles, faculty, students, and staff can participate in The Engine activities without real or perceived conflicts of interest or conflicts with their obligations to MIT’s research and educational missions. Senior members of the MIT administration should reinforce the need to adhere to these principles with visible endorsements of support.

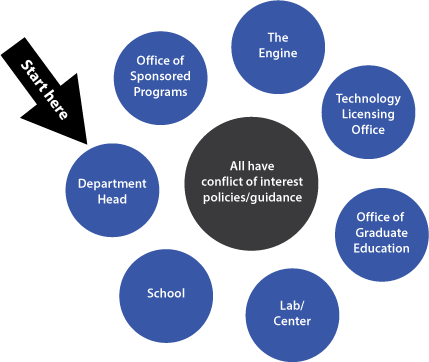

Increase Community Understanding

Every member of the community must understand the guiding principles behind MIT’s COI processes and be equipped to recognize potential conflict situations. Our working group recommends that the Institute commit the requisite resources to expand on existing efforts to develop more user-friendly tools and produce guidance documents that address the administrative burden on our faculty and community. Such resources are necessary to our ongoing efforts to demonstrate an exemplary model for how fCOI is understood and managed by a leading university in a uniquely complex and creative environment.

Expand Organizational Conflict of Interest Processes

From time to time, MIT takes equity in companies to which it licenses IP. Because MIT is an investor in The Engine’s accelerator fund, it will have an indirect economic interest in more startup companies. The potential for OCI, or perception of OCI, is likely to increase. Our working group expects that OCI concerns will arise primarily from MIT’s equity interest in startups licensing MIT IP, and we are reviewing how and when the Institute collects the information it needs to make informed decisions about mitigating OCI.

Be More Flexible in Allowing Low-Risk Activities

MIT should consider evaluating risk in a way that offers more flexibility for faculty, staff, and students to participate in startups. Customized arrangements could potentially allow startups to use MIT facilities and to seek funding for research they undertake. To implement such new arrangements, the Institute may need additional mechanisms that enforce COI management plans, minimize disruption to timely completion of academic degrees, and prevent the division of lab personnel and staff into “haves” and “have nots.”

Develop Mechanisms for Ongoing Review

Given the novel attributes of The Engine’s mission and structure, our group recommends that MIT develop new mechanisms for ongoing review of COI and OCI policies. These assessments should include risk/benefit analyses of policy changes developed in response to experiences with The Engine, other startup activities, and best practices at peer institutions.

How We Get There from Here

With respect to The Engine and potential COI, MIT should pursue twin goals: increase opportunities for its faculty, staff, and students to participate, and minimize or eliminate the risk factors. Our working group believes that increased education, standardization, and new licensing approaches are key to achieving these goals.

Expand and Refine Community Outreach

We recommend that MIT create a common web portal to educate the Institute community about new and existing COI policies and procedures, including a section focused on the broad range of issues related to startups. MIT also should develop constituent-specific materials tailored to the particular circumstances of faculty, staff, and students.

Investigate New Strategies in MIT’s Technology Licensing Office

The TLO could prioritize potential COI and OCI issues early in its licensing activities. Forethought and planning by the TLO could significantly minimize or even eliminate COI and OCI issues for MIT and its community members.

Create a Committee for Review of COI Policies

MIT should establish a new committee comprising faculty members, postdocs, students, and administrators to review inconsistencies in COI policy interpretation. This committee also could recommend changes to existing policies to make sure that they continue to support MIT’s innovation and entrepreneurial initiatives.

Open Questions

In the course of our review, our working group identified a number of issues and questions that require further study.

- What best practices from peer institutions should MIT consider adopting?

- How can the Institute best prioritize long-term impact ahead of short-term gain when considering new policies?

- What mechanisms should MIT use to review and reevaluate its role in encouraging participation by its faculty, staff, and students in The Engine while maintaining policy compliance?

- To what extent can MIT establish standardized interpretations of what can and cannot be done under existing policies and procedures? In particular, can the Institute develop standard interpretations for the following sections of MIT Policies and Procedures?

- Section 2.3 (Academic Instructional Staff Appointments)

- Sections 4.4 and 4.5 (Faculty Rights and Responsibilities on COI and OPA)

- Sections 5.2 and 5.3 (Sponsored and Academic Research Staff Appointments)

- Section 8.0 (Graduate Student Appointments)

- Section 12.5 (Use of Facilities)

- Section 13.1.5 (Information Policies/Consulting Agreements)

As we considered various scenarios, our working group identified a number of policy issues that require clarification in the areas of relationships, facilities, and startups.

Relationships

- How does MIT define “student?” For example, are students distinguished by their rank (e.g., undergraduate, graduate), or are all students treated equally under Institute policies?

- Should MIT consider postdocs to be staff rather than trainees? Should they be afforded acceptable allowances to participate in outside professional activities as part of their training?

- What is MIT’s perspective on the relationships that faculty, staff, and students may have with startups? For example, does MIT allow all or only some of these categories of individuals to provide consulting services? Are any individuals required to take leaves of absence or a reduced appointment at the Institute to work at a company?

- Do a person’s efforts in starting a company count as consulting for the purposes of our policies? In other words, is “consulting” as used in MIT Policies and Procedures intended as a proxy for “outside professional activities?”

Startups

Can a startup company with which a faculty member is involved fund research in that same faculty member’s lab?

Can faculty members and their startups co-apply for federal money (with a sub-award arrangement, for example)? If yes, what mechanisms (if any) do faculty members need in place to make such an arrangement allowable (e.g., limiting the arrangement to less than a year, requiring a co-investigator on the project who is not affiliated with the startup, etc.)?

Additional background information for the Conflict of Interest section may be requested at theenginewg@mit.edu.

Footnotes

- [1] Authors’ note: All linked terminology in this section is defined in MIT’s online “Financial Conflicts of Interest in Research: Definitions.” http://coi.mit.edu/policy/definitions#fcoi.