MIT's Innovation Ecosystem

Overview

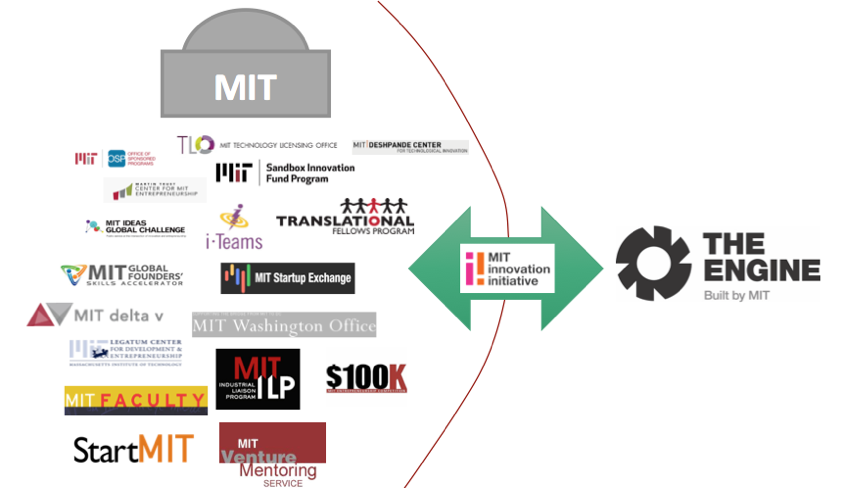

MIT is home to more than 85 centers, programs, competitions, prizes, hackathons, and student groups focused on innovation and entrepreneurship. This vibrant landscape has grown and evolved over time. It often coalesces into novel collaborations that create supportive pathways for students to advance ideas and technologies that benefit the world.

The Engine Working Group on MIT’s Innovation Ecosystem convened leaders from many of these entities to develop recommendations on how to prepare the Institute’s diverse population of students, postdoctoral researchers, faculty, and staff for entrepreneurial ventures beyond their time on campus—whether through The Engine or other external programs. As a group, we discussed ways to strengthen available resources, enhance community, and ensure an inclusive approach to innovation and entrepreneurship. Our goals included proposing strategies to coordinate and connect existing programs, and generating ideas for new opportunities.

Where We Are Today

Over the past several years, staff from many MIT innovation and entrepreneurship centers have interviewed students and alumni to learn how those groups were locating and leveraging campus resources. Our Innovation Ecosystem Working Group built on that research by conducting additional in-depth interviews with special emphasis on policies and procedures. We have begun to integrate evidence from multiple sources and to clarify what is presently available on campus, how resources are being used, where gaps exist, and how MIT policies create challenges for startups.

Highlighting Ecosystem Strengths and Weaknesses

With the help of recommendations from groups on campus, we have identified more than 80 MIT ventures that fit the general description of the “tough-tech” startups that The Engine is targeting. During our initial round of interviews, we asked some of these startups about their journeys—from pre-founding technology development through growth phase—within and beyond the MIT ecosystem.

Those interviews highlighted the strengths of the current portfolio of MIT resources and revealed critical gaps—both in support and in understanding the complexities and nuances of the startup process. We interviewed current students and postdocs launching companies today, entrepreneurs involved with companies that launched more than a decade ago, and those connected to enterprises that have successfully exited.

Interviewees shared positive comments about the vast array of available resources and the effectiveness of certain mentors. They also noted a variety of obstacles and challenges related to conflicts of interest, gaining access to facilities, and maintaining MIT affiliations or work eligibility in the United States.

Seeking Transparency and Guidance

Regardless of whether interviewees described positive or negative experiences with MIT resources, all our conversations touched on a common need—better communication about the organizational decision-tree that potential startups must follow when founding a company while on campus.

This universal need is independent of mentoring on strategy and entrepreneurial skills. Instead, it reflects the need to gain an early understanding of the legal ground rules and boundaries for starting a company at MIT. Interviewees felt underprepared for challenging decision points and underestimated the potential for conflict and complexity.

Understanding Future Consequences of Early Decisions

Interviewees often cited concerns about their own lack of experience when making critical decisions during the startup process. They said they felt ill equipped to assess the broader implications of their early decisions. They also emphasized the need for greater support during some of their more difficult conversations with the MIT faculty or administration. Even former students and researchers who had positive experiences navigating the system, including those who attributed their success to a single advocate on campus, expressed a desire for more guidance.

What We Need

No one we interviewed in connection with this report expected that founding a venture, especially one licensing MIT technology, would be a simple process. Everyone agreed, however, that MIT presently does not have an optimized or equitable startup support process. Participants identified a number of common concerns about and gaps in the Institute’s existing innovation ecosystem.

Address Confusion About Who Can License What

Who is allowed to start a company utilizing MIT technology? What happens if more than one party wishes to license the same technology? Multiple interviewees discussed situations in which both a student and a faculty member were interested in starting a company based on their common lab research. Although collaborative relationships were negotiated and launched in many cases, outcomes were not always satisfactory or equitable.

For purposes of strengthening the MIT ecosystem, and without casting judgment on either side of this dispute, we note as an example one case in which a student in that situation identified a lack of institutional support. The student found the process of determining licensing rights to be unclear and expected to receive more assistance from MIT in navigating the conflict, despite having participated in a variety of committee meetings and hearings related to the matter. The student did report receiving strong support from a team of mentors assembled by the MIT Venture Mentoring Service, which helped navigate the often-difficult conversations.

Understand the Implications of Incorporation

Many founders of MIT startups did not come to campus intending to study business or launch a venture (this is especially true of those in technical programs). When later-stage students or postdocs recognized the potential impact of translating a project to the world through an entrepreneurial vehicle, they often lacked basic startup skills. As a result, they began hacking their way through venture construction without understanding the implications of officially incorporating a company. This was also true of many first-time faculty founders.

While serial entrepreneurs took parts of the process for granted, the first-time founders we interviewed described a complicated and uncertain journey. They struggled to assess what was best for themselves and their prospective ventures. Questions of timing were often complicated by the fact that they intended to license MIT technology and were using campus facilities for their work.

As noted earlier, many individuals succeeded with the help of mentoring provided by the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, MIT Venture Mentoring Service, and Deshpande Center. A significant number, however, still encountered challenges or had to navigate the process alone. These individuals suggested that MIT find better ways to inform entrepreneurially minded students about the startup process, decision trees, and the implications of early decisions. All believed that greater transparency about available programs would help innovators find trusted advocates across all domains.

How We Get There from Here

Our working group recommends that MIT strengthen community-wide understanding of the various Institute guidelines governing entrepreneurial processes on campus. Specifically, MIT needs to clearly articulate policies for all aspects of the startup process. MIT should communicate its policies in a connected and comprehensive fashion using stories and similarly accessible genres that reflect the lived experience of entrepreneurs.

Coordinate Across Working Groups

Our working group recommends continued coordination among the five working groups that contributed to this report. Our initial findings reveal how extensively these five topic areas interconnect and highlight the need to address issues holistically. Ongoing coordination will magnify the benefits of these efforts for MIT’s entrepreneurial community.

Develop and Disseminate New Policy Guides

Although MIT maintains various rules and guidelines related to startup activities, it needs to communicate them more vigorously. Our group recommends that the Institute collaborate with its innovation and entrepreneurship centers to develop user-friendly policy guides that address the key issues raised in this report.

These guides should incorporate real, anonymous case studies from within the MIT ecosystem. Relating the application of abstract policies to real-life situations will help demonstrate how the guidelines apply to concrete situations. Guides can be promoted and disseminated jointly by the many innovation and entrepreneurship (I&E) groups on campus through various channels—online, print, and live presentations.

Recruit and Train Innovation Advocates

MIT could magnify the impact of existing I&E centers on campus by recruiting and training a team of innovation advocates from among our faculty and staff. These advocates would be certified as experts on the ins and outs of MIT policies governing technology licensing, facilities access, relevant visa issues, and conflicts of interest.

Refine and Document Rules of Engagement

Informed by years of experience, entities such as the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship and Venture Mentorship Service have developed a set of principles for student support. These honest-broker principles are meant to ensure that programs remain focused on educational value. The principles enable students to trust that the advice they receive from MIT staff and external mentors is unbiased and rooted in students’ best interests. More recently founded centers, such as MIT Sandbox, adopted these principles during formation to promote a standard operating system for the internal MIT ecosystem.

Our working group recommends the development of an aligned set of principles of engagement for the interface between the Institute community and The Engine. Mutual understanding among students, MIT staff, and The Engine staff about similarities and differences in the structure and objectives of campus programs and The Engine is essential. These principles of engagement should be codified, clearly stated, and well publicized.

Establish Shared “Proto-Engine” Community Space for Startup Teams

In between the hatching of an initial idea and an official launch, MIT entrepreneurial team members often struggle with the interim phase—exploring viability, markets, and technical feasibility—while still students or affiliates of MIT. Many described the potential value of a new shared space for teams, space that teams could use before they incorporate or graduate from their programs.

Although the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship recently expanded, its new space is already overtaxed and unable to provide even semi-permanent homes to the most dedicated MIT teams. An on-campus “proto-Engine” space that convenes such teams from across a wide variety of campus centers would provide much needed support and lead to greater cross-pollination among centers and departments.

Develop an Innovation Master’s Program

In addition to space constraints, many students cited the challenge of fully exploring an idea and developing innovation skills while simultaneously meeting the rigorous requirements of a degree in engineering, science, architecture, humanities, or management. At graduation, they lose their MIT affiliations just as they are ready to leap fully into entrepreneurship. Our group proposes the creation of an innovation master’s program that builds upon domain-specific skills, offers hands-on internship experience in a startup, and furthers students’ innovation skills as they pursue their ideas. This recommendation builds on the similar idea proposed in the Visas for Entrepreneurs section.

Continue Data Collection and Analysis

Our working group recommends ongoing high-level, programmatic data collection across the various competitions, programs, and centers at MIT to track who participates in such programs and how they benefit from participation. Such data collection could include a collaboration with Institutional Research (IR) that explores the incoming and outgoing entrepreneurial aspirations and actions of MIT students at different stages in their education. This could be achieved by adding a simple set of questions to an existing IR questionnaire.

This macro-level information, combined with program- and center-level data, would help MIT understand which students are best served by the existing network of resources throughout campus. The Institute could use this data to target areas where additional outreach and new offerings would deliver the greatest impact.

Open Questions

Although we gained many useful insights from our initial set of interviewees, our working group is aware of dozens more MIT companies that are eager to discuss their journeys through the Institute’s entrepreneurial landscape. Our goal is to engage with these organizations and update the Institute on how it can better support its aspiring entrepreneurs. We hope to explore three questions that overlap with key issues raised by the other working groups associated with this report.

- What conflicts might arise with my lab advisor or other colleagues if I attempt to launch a company?

- What constitutes significant use of MIT facilities, and why does that use matter?

- What are the rules governing what international students may and may not do in founding startups?

“As we continue to expand the Institute’s innovation ecosystem, more MIT students and faculty will become entrepreneurs. That will be good for our country—and for society.”

—Ray Stata, Co-Founder of Analog Devices