| Vol.

XXIII No.

3 January / February 2011 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

MIT's Approach to International Engagement

This article describes MIT’s approach to international engagement. It starts by explaining why MIT engages internationally, and then shows how – appropriately for our entrepreneurial community – MIT has many approaches to international engagement, not just a single, centrally coordinated “international strategy.” It then explains our present approaches to these engagements, followed by a description of MIT’s funding model, a few examples of today’s many international activities, and a brief summary of some of the risks of engaging – or not engaging – internationally. The article ends with an evolving vision of MIT that connects many of our international activities to MIT’s enduring global themes: bringing knowledge to bear on the world’s great challenges and educating the global leaders of tomorrow. In our international activities, as in all we do, the overriding intent is to make MIT stronger and to reinforce MIT’s position as one of the leading science and technology academic institutions in the world.

Many of the criteria discussed in this article are applicable to our domestic activities as well. The focus, however, is on MIT’s present international activities and their benefits to MIT. Of course, we also want our partners, collaborators, and sponsors to benefit as well from their engagement with MIT.

It is important to recognize, at the start, two important realities:

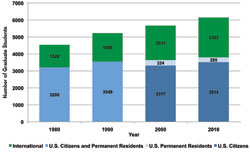

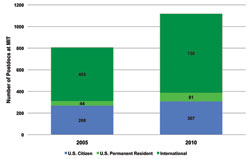

MIT’s talent composition is international. MIT, like other leading institutions of higher education in the U.S., has benefited tremendously from its ability to attract talented students, faculty, and staff who, for a variety of reasons, choose to leave their home countries to come to the U.S. MIT has been an institution open to international talent for a long time. At present, over 40% of our graduate students (see Figure 1), over 70% of our postdocs (see Figure 2), and about 40% of our faculty were born outside the U.S. This international profile has benefited, and continues to benefit, MIT and the U.S. enormously.

(click on image to enlarge)

U.S. postdocs at MIT, 2005 and 2010.

(click on image to enlarge)

MIT’s problem-solving ambitions are global and we cannot solve the most important world problems alone. MIT certainly focuses on problems important to the U.S. For example, MIT conducted the “Made in America” study in the 1980s, and has launched the recently announced initiative on Production in the Innovation Economy. But MIT has also focused on global problems, addressing concerns that go beyond the geographical boundaries of the U.S. (e.g., MIT’s Energy Initiative). In order to do the latter, MIT has been collaborating with individuals and entities inside and outside the U.S. These collaborations benefit the U.S., MIT, and our partners.

I. Why does MIT engage internationally?

MIT faculty members have been engaging internationally for a long time. Why? Because they find collaborators they want to work with, and/or laboratory facilities they want access to, and/or research and education opportunities they find attractive (e.g., an appropriate region to test new ideas for greatest impact or to access data), and/or research sponsors they do not find in the U.S. In addition, MIT academic leaders – deans, department and program heads, center and lab directors – sometimes initiate international activities when it benefits their units and when the activities can be integrated into the larger intellectual context of the units. MIT academic leaders also want to provide educational opportunities to prepare their students to become global leaders. The MIT central administration becomes involved in international activities when it is important to provide a larger, broader MIT context. Regardless of how an international activity is initiated, our faculty and students have benefited significantly from a variety of such interactions. In recent years, the opportunities and motivations for international engagement have expanded considerably, with several factors helping to explain this trend, including:

Relevance. There was a time when MIT and other U.S. academic institutions worked solely on problems of interest to the region and/or the nation. Of course, MIT faculty members still focus on such issues. But in general, our faculty want to work on the most important challenges of the day, and many of these challenges extend beyond national interest to global importance. To quote from MIT’s mission statement: “The Institute is committed to generating, disseminating, and preserving knowledge, and to working with others to bring this knowledge to bear on the world's great challenges.” The world’s great challenges do not have national boundaries. By engaging internationally, we can (i) monitor progress of worldwide efforts, (ii) learn from others at the same time that we extend our own expertise, (iii) provide global network opportunities for MIT students and faculty, and (iv) enable our faculty and students to connect with MIT alumni, global companies, and our partners worldwide. Moreover, even though the U.S. will continue to be a source of inspiration for new ideas in research and education, many creative ideas will emerge or be implemented first elsewhere. Consequently, it is essential to MIT’s continuing strength that our faculty and students remain closely engaged with the increasingly interconnected and expanding world of ideas and innovation.

Talent. At present, several nations are trying to emulate the U.S. academic system of education and research, and they are moving toward closing the gap by increasing their investments in these areas. American institutions, including MIT, have benefited significantly from being situated in the strongest economy in the world, and this has helped them attract some of the world’s most talented scholars and researchers. As the economies of other nations strengthen, and as these nations invest in their local institutions, their ability to attract the best international talent will increase dramatically.

We are already beginning to experience difficulties in retaining talent at MIT against competition from international institutions, reflecting an increase in competition for young talent globally. International activities make it possible for the Institute to stay connected and engaged with excellent talent worldwide, and increase our opportunities to attract some of this talent to MIT.

Evolving educational vision. We need to educate our students to understand the world, in order to prepare them to compete globally and to become the global leaders of tomorrow. Our students’ exposure to the international community that comprises MIT strengthens their understanding of the world as well as their education as future global leaders. It also is important to provide our students with opportunities for meaningful international experiences abroad, and close faculty involvement is necessary to ensure that international components of a course of study conform to MIT educational standards and expectations. In addition to educating our own students, it is important for MIT to contribute to the education of future global leaders who may not be able to attend MIT. The U.S. and the world benefit from the kind of education that MIT provides, and we should carefully consider opportunities to integrate our educational expertise into our international activities.

Funding. It is prudent and beneficial to diversify and expand MIT’s funding sources. Not only is this a good policy, but it is also a natural evolution reflecting a more international and globally connected institution. As with talent, these funding sources are increasingly found overseas. For example, the Institute’s sponsored research expenditures coming from international sources nearly quadrupled over the last 10 years to $96 million in FY2010 (see M.I.T. Numbers). This corresponds to an increase in the proportion of total campus-sponsored research expenditures funded by international sources from approximately 7% in 2001 to about 15% in FY2010.

| Back to top |

II. When referring to “MIT’s International Strategy,” who is MIT?

Only a handful of individuals can make a commitment or sign a formal document on behalf of MIT. Nevertheless, MIT has about 1,000 faculty members, including more than 30 heads of academic units and more than 50 directors of interdepartmental Labs/Centers/Institutes/Initiatives, five School Deans and three Deans for students and education. In addition, MIT has an office for Resource Development, including directors of Foundation and Corporate Relations. When any one of these individuals (or offices) speaks with an international entity or individual (whether public, private, government, commercial, or industrial), the international entity or individual often assumes the conversation is being conducted with “MIT.”

Consequently, even though many members of the MIT community, including our alumni, would like to see a greater degree of coherence in our international engagements, and would expect this coherence to flow from the central administration (i.e., from the President, Provost and/or Chancellor), the reality is that most of our engagements are neither initiated by, nor explored in coordination with, the central administration.

Hence, in a dynamic and entrepreneurial community such as ours, it is not possible to speak of the “MIT International Strategy,” if that refers to a coherent set of activities taken up by MIT faculty, departments, and Schools in response to a cohesive, centrally coordinated strategy. On the contrary, marching in lockstep in this way would not be desirable, as the best ideas at MIT are those that originate with, and flow from, the students, faculty, and staff. On the other hand, the central administration does have a coherent global strategy and an approach to international engagement that is consistent with the exciting and entrepreneurial nature of our community.

III. MIT’s approach to international engagement

MIT faculty and academic leaders are free to pursue engagements and seek access to collaborators, facilities, and sponsors that will benefit them and their partners, whether in the U.S. or abroad. In supporting these initiatives, MIT expects that the engagement be consistent with our policies regarding faculty commitment to MIT and with MIT’s mission, principles, and values. When dealing with international activities on any level, it is particularly important to assess the reputational risk to MIT before starting an engagement, and to monitor this risk continuously during the engagement. Moreover, it is also important to recognize that regulatory issues applicable to international engagements add additional layers of compliance, complexity, and cost.

As mentioned earlier, in addition to faculty and academic leaders, the central administration occasionally pursues international initiatives that reflect a broader or more formal commitment on an institutional level, particularly those that offer our faculty and students access to (i) talent (i.e., students, postdocs, faculty, other researchers), (ii) ideas and collaborations, (iii) facilities and research infrastructure, (iv) research and educational funding, (v) opportunities to educate future global leaders, and (vi) opportunities to work on the world's great challenges. Usually such initiatives involve some level of partnership with a foreign university (or group of universities), foundation, or government agency, and come with a strong expectation of lasting benefits to MIT as well as to our partners. By and large, the central administration takes a proactive role in launching or shaping international activities when these are in support of a larger strategic goal for MIT.

How does the MIT central administration choose where to engage? Ideally, the potential international engagement ought to offer most of the following:

- Intellectual content of high interest to our faculty

- Talent, ideas, and resources

- Expectation of long-term commitment

- Potential for long-term impact

- Potential to integrate research and education

- A partner that values science and technology (S&T)

- A partner that values knowledge creation and applications

- A partner that recognizes the impact of S&T on the economy and society

- Scale of engagement that involves multiple disciplines

- Engagement in a current and/or future regional hub for innovation

- Engagement in a region with significant MIT alumni presence and the potential for involving them

- Engagement consistent with MIT’s values and principles

Consistent with MIT’s mission to “work wisely, creatively, and effectively for the betterment of humankind,” MIT should also support initiatives that pursue, where appropriate, activities that include a service dimension in underprivileged countries or regions that could greatly benefit from MIT’s expertise, while at the same time providing MIT faculty and students with challenges to solve important problems.

The MIT central administration has practiced both a responsive and a pro-active approach to international involvement. At this time, we are proactively exploring possible opportunities in China, India, Russia, and Brazil, complementing perceived faculty interest in these countries.

We recognize, however, that there is limited capacity for such engagements of significant breadth, and that there are opportunity costs associated with these activities (e.g., participating in a large engagement in a given country may prevent us from participating in an important and desirable engagement in another country).

One way that we assess and monitor our international engagements is through MIT’s International Advisory Committee (IAC), which is co-chaired by Associate Provost Philip S. Khoury and Vice President for Research and Associate Provost Claude R. Canizares. The IAC assesses international engagements by focusing on (i) consistency of the engagement with faculty’s commitment to MIT, (ii) alignment of the engagement with MIT’s mission, principles, and values, and (iii) reputational risk of the engagement to MIT. The IAC also seeks to learn from past and ongoing activities in order to apply that experience to future activities.

The IAC sponsors faculty Working Groups engaged in designing possible strategies by countries and regions. A recent example is the “MIT-Greater China Strategy” Report (available at: web.mit.edu/provost/reports/Final-GCSWG-Report-August-2010.pdf). These IAC Working Groups advise the administration and provide regional guidance to faculty interested in working in specific regions.

In short, MIT’s approach to international engagement can be summarized as follows: (i) activities that emerge from academic leaders, faculty, students, and staff take many forms but should be consistent with MIT’s mission, principles, and values, and the MIT central administration plays an important role ensuring that this is the case, and (ii) activities initiated by the central administration are guided by a coherent strategic vision that strengthens MIT and is consistent with the entrepreneurial nature of our community.

IV. Funding model

With few exceptions, research and education sponsorships at MIT cover all (i.e., direct and indirect) project-related costs (exceptions include a few not-for-profit U.S. sponsors). Similarly, international sponsors also are expected to cover all direct and indirect research and education costs. However, larger-scale international sponsorships, particularly those initiated by the central administration, are typically asked to provide financial support beyond direct and indirect costs. Why is that?

International activities often require our faculty to travel away from MIT, creating an absence on campus that usually needs to be addressed. Moreover, due to their complexity, these activities typically require additional oversight, and in some instances governance commitments. Some large international engagements may require the active participation of members of MIT’s central administration and ongoing support from MIT administrative offices such as finance, research administration, and technology licensing. As we engage in institution building overseas, we should seek resources to renew and strengthen MIT, i.e., to fund our own institutional renewal.

As a result, international sponsorships initiated by the central administration are typically asked to contribute to MIT’s endowment in addition to covering all direct and indirect project costs. Some of this endowment could be used, for example, to create new faculty lines to offset the additional call on faculty time.

As indicated in Section III, some members of our community also work in regions of the world that significantly benefit from MIT expertise but which cannot afford to fund the engagement. MIT believes these activities are important as well, and is exploring ways to provide seed funds while the interested faculty members seek more stable support. There may also be cases where our strategy would be best served by MIT providing an initial investment of resources to help develop collaborations with particular countries, leading to possible longer-term engagements that would conform with the funding model for larger-scale projects described above.

| Back to top |

V. MIT’s international activities: a few current examples

As noted at the beginning, MIT has engaged internationally for a long time, whether participating in research collaborations or in institution building. An article by S.W. Leslie and R. Kargon (“Exporting MIT: Science, Technology and Nation-Building in India and Iran,” The History of Science Society, pp. 110-130, 2006) describes MIT’s role in the establishment of the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur (IIT/Kanpur), and the Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS) in Pilani in the 1960s, as well as the Aryamehr University of Technology in Iran, in the 1970s. Why do MIT faculty engage with people and entities elsewhere, not just elsewhere in the U.S., but abroad as well? The answer is simple: because it benefits our faculty, it benefits our students, and it benefits society.

Our international involvement today comes in different forms, and its expanse is breathtaking. It covers a broad range of activities, from interactions with a partner/collaborator/sponsor, to faculty activities in regions where the necessary research infrastructure is available, to a variety of student internships. This section highlights only a few current examples of research and educational collaborations, student internships and exchange programs (of course, the classification used here is arbitrary and not thorough). The examples below are a mix of faculty-led initiatives and initiatives driven by the central administration.

Research collaborations. There are many individual MIT faculty collaborations with researchers in other institutions in the U.S. and abroad. There are also individuals and groups of MIT faculty engaging elsewhere in collaborations that provide access to research facilities we do not have at MIT. An example of the latter is the research our high-energy physicists have been conducting at CERN in Europe. In fact, numerous examples of spectacular research done by our Physics faculty at the facilities of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California and of Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York underscore the point that our faculty go wherever necessary to access the facilities (and collaborators) they need for their research. In the case of CERN, those facilities are outside the U.S.

A new model for global engagement emerged with the establishment of the SMART (Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology) Center in 2007 in Singapore.

The SMART Center offers our faculty, students, and postdocs the opportunity to collaborate with talented researchers in Singapore and elsewhere in Asia who have complementary expertise; it also provides access to Singapore’s complementary facilities, and to research issues that benefit from study in the region (e.g., local infectious diseases).

Education collaborations. Just as MIT faculty helped establish new universities elsewhere in the 1960s, they continue to do so today. The Masdar Institute (MI) in Abu Dhabi, established through the Technology and Development Program in 2009, is a graduate-level institution dedicated to energy and environmental sustainability. The Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) will matriculate its first students in April 2012 and will offer a multi-disciplinary curriculum focused on design. MIT faculty participate in these institution-building activities partly driven by their sense of mission, but also partly to engage in activities they find intellectually stimulating, such as developing new curricula (which also benefit MIT) and integrating state-of-the-art research with the education of future global leaders unable to attend MIT. Moreover, MIT faculty benefit from opportunities and resources to carry out research in important fields (e.g., sustainability and design).

Student internships. An example of an international program with a focus on MIT students is MISTI (MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives), based in the Center for International Studies, which connects MIT students (and faculty) with research and innovation around the world. By working closely with premier international corporations, universities, and research institutes, MISTI matches hundreds of MIT students annually with internships and research opportunities abroad. In addition, MISTI provides funding for MIT faculty to jump-start international projects and encourages student involvement in faculty-led international research. Another example is D-Lab, which fosters the development of appropriate technologies and sustainable solutions within the framework of the International Development Initiative. Like MISTI, D-Lab seeks to give students deep and meaningful experiences and is committed to making a long-lasting impact in the communities where they work. To this end, D-Lab provides an opportunity for students to engage in fieldwork and maintains strong relationships with partner organizations.

Student-exchange programs. An example of this kind of program is the Cambridge-MIT Exchange, which provides MIT and University of Cambridge undergraduate students the opportunity to study for one year at the partner institution.

An example of an activity that combines research, education, student exchanges, and internships is the Global SCALE (Supply Chain and Logistics Excellence) Network, established in 2008 in the Center for Transportation and Logistics. This network currently includes logistics centers in Spain (Zaragoza), Colombia (Bogota), and at MIT.

These are just a few examples of the tremendous breadth of engagements in which our dynamic and entrepreneurial faculty, students, and staff participate, as well as initiate.

Examples that MIT does not include in its portfolio at this time are satellite campuses and conferring MIT degrees elsewhere. We will come back to this in section VII.

VI. Risks of action and of inaction

There are several risks of action, among them:

- Reputational. For example, as a result of MIT

- Not fulfilling its obligations and/or commitments, and/or

- Not meeting its collaborating partner’s expectations, and/or

- Not understanding or anticipating mismatched expectations

- Political or cultural. For example, as a result of

- U.S. foreign policy, and/or

- Host country shifts in political conditions, and/or

- Host country cultural differences

In addition to these risks, there is the important issue of faculty workload. With increasing global engagements, the load on our faculty may increase. A possible solution could be an increase in the size of our faculty.

There are, of course, several risks of inaction. Among them is the risk of jeopardizing MIT’s position as the place (or one of the top places) “where the action is” in science and technology. It is clear that outstanding S&T international talent gravitates toward major centers of activity, i.e., where the future is being invented, and where the most creative, novel, and groundbreaking research is being carried out. MIT is one of those places in the world, attracting outstanding talent. MIT should continue to work on the most important problems our nation is facing, and it should continue to work on the world's great challenges. The latter suggests that MIT must engage globally to continue to attract some of the best international talent. Inaction not only risks our ability to continue to attract the best talent to MIT, but also risks the ability of our faculty and students to stay engaged with many of the most innovative ideas being generated worldwide. The risk of inaction is that, over time, MIT may lose the S&T preeminence it enjoys today.

VII. An evolving vision

As already stated, it is MIT’s responsibility to prepare our students to understand the world and to engage and succeed in a globally competitive environment in order to become the global leaders of tomorrow. At the same time, it is important for MIT to consider expanding its educational reach and participating in the preparation of future global leaders who are unable to attend MIT.

At present, MIT is neither establishing satellite campuses, nor is conferring MIT degrees elsewhere. Instead, a possible alternative model for extending MIT’s international involvement is to establish a global network of research and educational institutions that focus on science and technology and that share MIT’s values and principles. These institutions would be located in present or future regional hubs of innovation.

Examples might include MIT’s SMART Center in Singapore, MI in Abu Dhabi, and SUTD in Singapore. These institutions, whether established as part of MIT (e.g., SMART) or in collaboration with MIT (e.g., MI, SUTD), could potentially become part of a network of institutions that will not only enable MIT students, faculty and staff to engage globally, but will also enable MIT to contribute to the education of future global leaders attending those other institutions. Moreover, in the future, the education of an MIT student may combine time at MIT with time at one or more institutions that are part of this “MIT global network.” This strategy allows MIT to (i) strengthen local institutions in geographically diverse regions, (ii) interact with, and participate in the education of, student talent in those institutions, (iii) provide unique opportunities to prepare our students to understand the world and to compete globally, and (iv) collaborate with complementary expertise and in complementary facilities to solve the world’s great challenges. All these activities, when properly funded and administered, strengthen MIT. MIT’s Sloan School of Management is already assisting partner schools to become leading institutions in their home countries, and exposing MIT faculty and students to collaborations with counterparts from those countries.

MIT could further expand its participation in the education of future global leaders by offering credentials for learning MIT-content on-line. MIT students could participate in this mode of education while attending the “MIT global network” of institutions, or when doing internships abroad. In other words, this would benefit not only students who cannot attend MIT, but also MIT students spending time elsewhere.

VIII. Summary

MIT faculty, academic leaders, and the central administration pursue mutually beneficial engagements in the U.S. and abroad. They do so because these engagements allow access to talent, collaborations, ideas, facilities, and/or funding. Furthermore, in line with MIT’s mission, they allow us to work “with others to bring this knowledge to bear on the world's great challenges.” These engagements strengthen MIT’s ability to continue to attract and retain some of the best international and domestic talent. They also allow MIT to better prepare our students to understand the world, to compete globally, and to become the global leaders of tomorrow. As part of our institutional strategy, we should consider expanding our role globally, such as participating in the education of future global leaders who are unable to attend MIT. MIT’s global engagement will become more important with time, and will reinforce MIT’s position as one of the leading science and technology academic institutions in the world.

Note: This article will be posted on the Provost’s Office Website (web.mit.edu/provost) and is intended to reflect a “live” strategy, that is, it will be updated periodically as appropriate.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |