User’s Guide, Chapter 2: Notes¶

Notated music, by its very name, consists of a bunch of notes that are put one after another or simultaneously on a staff. There are other things, clefs, key signatures, slurs, etc. but the heart of music is the notes; so to get anywhere in music21 you’ll need to know what the toolkit thinks about notes and how to work with them.

Go ahead and start IDLE or type “python” at the command line (Terminal on the Mac or “run: cmd” on Windows) and let’s get started.

Creating and working with Notes¶

The music21 concept of a standard note is contained in the

Note object, which is found in the note

module.

Read this if you’re new to Python (others can skip ahead): Notice

the difference between object names and module names. Modules, which can

contain one, many, or even zero objects, always begin with a lowercase

letter. Music21’s objects always begin with a captial letter. So the

Note object is found in the note module. The distinction between

uppercase and lowercase is crucial to Python: if you type the name of an

object with the wrong case it won’t know what to do and won’t give you

any help in distinguishing between them.

In the note module, there are other classes besides note.Note.

The most important one is note.Rest, which as you imagine represents

a rest. If we load music21 with the command:

from music21 import *

then you’ll now be able to access the note module just by typing

note at any command line.

>>> note

<module 'music21.note' from 'D:\music21files\music21\note.pyc'>

note module any time you type "note". The filename after “from

‘D:\music21files…’” will differ for you. It will show you where you

have music21 installed (if you ever forget where you have music21

installed, this is an easy way to figure it out).note.pyc or note.py or something like

that you’re fine.If you want to know what else the note module contains besides the

Note and Rest objects you can type “dir(note)” to find out:

dir(note)

['GeneralNote',

'Lyric',

'LyricException',

'NotRest',

'NotRestException',

'Note',

'NoteException',

'Rest',

'SYLLABIC_CHOICES',

'Unpitched',

'noteheadTypeNames',

'stemDirectionNames']

Some of the things in this list are classes of notes – they are

capitalized. Other classes are things that we’ll get to later, like

Lyric objects.

(By the way: I’m highlighting the names of most objects so they become links to the full documentation for the object. You can read it later when you’re curious, frustrated, or Netflix is down; you certainly don’t need to click them now).

(Advanced digression):¶

If you’re more of a Python guru and you’re afraid of “polluting your

namespace,” instead of typing “from music21 import *” you can type:

import music21

in which case instead of using the word note, you’ll need to call it

music21.note

>>> music21.note

<module 'music21.note' from 'D:\music21files\music21\note.pyc'>

If you are a Python guru, you already knew that. Probably if you didn’t

already know that, but you’ve heard about “polluting your namespace,”

you have a Python guru friend who has screamed, “Never use

import *!” Trust me for now that this tutorial will be easier if you

ignore your friend for a bit; by the end of it you’ll know enough to be

able to follow whatever advice seems most natural to you.

(Back from the Python digression and especially the digression of the digression):

Okay, so now you now enough about modules and objects. Let’s create a

note.Note object. How about the F at the top of the treble clef

staff:

f = note.Note("F5")

We use the convention where middle-C is C4, the octave above it is C5, etc.

Now you have a Note. Where is it? It’s stored in the variable f. You

can verify this just by typing f:

f

<music21.note.Note F>

And you can see that it’s actually an F and actually in octave 5 by

requesting the .name and .octave attributes on the Note

object, f:

f.name

'F'

f.octave

5

And there’s an attribute called .pitch which returns another object:

f.pitch

<music21.pitch.Pitch F5>

Well, that didn’t tell you anything you didn’t know already! Let’s look

at some other attributes that might tell you something you didn’t know.

Some of them are sub-attributes, meaning they take two dots. Here’s a

sub-attribute on pitch, which we just said was itself an object,

called .frequency:

f.pitch.frequency

698.456462866008

And another sub-attribute called pitch.pitchClassString

f.pitch.pitchClassString

'5'

That’s a bit better! So an f is about 698hz (if A4 = 440hz), and it is pitch class 5 (where C = 0, C# and Db = 1, etc.).

A couple of things that you’ll notice:

Your

frequencyprobably has a bunch more numbers instead of ending with “…”. Mine gives me “698.456462866008”. In the docs, we’ll sometimes write “…” instead of putting in all those numbers (or long strings); it’s partly a way of saving space, and also because the length of a long number and even the last few digits will differ from computer to computer depending on whether it’s 32-bit or 64-bit, Mac or PC, number of sunspots last Autumn, etc. Since I don’t know what computer you’re using, don’t worry if you get slightly different results.There are single quotes around some of the output (like the

'F'inf.name) and none around others (like the5inf.octave). The quotes mean that that attribute is returning a String (a bunch of letters or numbers or simple symbols). The lack of quotes means that it’s returning a number (either an integer or if there’s a decimal point, a sneakingly decimal-like thingy called afloat(or “floating-point number”) which looks and acts just like a decimal, except when it doesn’t, which is never when you’d expect.

(The history and theory behind floats will be explained to you at

length by any computer scientist, usually when he or she is the only

thing standing between you and the bar at a party. Really, we shouldn’t

be using them anymore, except for the fact that for our computers

they’re so much faster to work with than decimals.)

The difference between the string '5' and the number 5 is

essential to keep in mind. In Python (like most modern programming

languages) we use two equal signs (==) to ask if two things are

equal. So:

f.octave == 5

True

That’s what we’d expect. But try:

f.pitch.pitchClassString == 5

False

That’s because 5 == '5' is False. (There are some lovely

languages such as JavaScript and Perl where it’s True; Python’s not

one of them. This has many disadvantages at first, but as you go on, you

might see this as an advantage). So to see if f.pitchClassString is

'5' we need to make '5' a string by putting it in quotes:

f.pitch.pitchClassString == "5"

True

In Python it doesn’t matter if you put the 5 in single or double

quotes:

f.pitch.pitchClassString == '5'

True

pitchClassString tells you that you should expect a string, because

we’ve put it in the name. There’s also a .pitch.pitchClass which

returns a number:

f.pitch.pitchClass

5

These two ways of getting a pitch class are basically the same for the

note “F” (except that one’s a string and the other is an integer) but

for a B-flat, which is .pitchClass 10 and .pitchClassString “A”,

it makes a difference.

Let’s go ahead and make that B-flat note. In music21, sharps are “#”

as you might expect, but flats are “-”. That’s because it’s otherwise

hard to tell the difference between the Note “b” (in this instance,

you can write it in upper or lower case) and the symbol “flat”. So let’s

make that B-flat note:

bflat = note.Note("B-2")

I’ve called the variable “bflat” here. You could call it “Bb” if

you want or “b_flat”, but not “b-flat” because dashes aren’t

allowed in variable names:

b-flat = note.Note("B-2")

File "<ipython-input-17-dff15d6dca04>", line 1

b-flat = note.Note("B-2")

^

SyntaxError: cannot assign to operator

Since this note has an accidental you can get it by using the

.pitch.accidental subproperty:

bflat.pitch.accidental

<music21.pitch.Accidental flat>

Here we have something that isn’t a number and doesn’t have quotes

around it. That usually means that what .accidental returns is

another object – in this case an Accidental

object. As we saw above, objects have attributes (and other goodies

we’ll get to in a second) and the Accidental object is no exception.

So let’s make a new variable that will store bflat’s accidental:

acc = bflat.pitch.accidental

We’ll get to all the attributes of Accidental objects in a bit, but

here are two of them: .alter and .displayLocation. You’ll use

the first one quite a bit: it shows how many semitones this

Accidental changes the Note:

acc.alter

-1.0

Since this Accidental is a flat, its .alter is a negative

number. Notice that it’s also not an integer, but a float. That might

indicate that music21 supports things like quarter-tones, and in this

case you’d be right.

Look back at the two lines “acc = bflat.pitch.accidental” and

“acc.alter”. We set acc to be the value of bflat.pitch’s

.accidental attribute and then we get the value of that variable’s

.alter attribute. We could have skipped the first step altogether

and “chained” the two attributes together in one step:

bflat.pitch.accidental.alter

-1.0

acc.displayLocation

'normal'

Good to know that we’ve set a sensible default. If you want to have the accidental display above the note, you’ll have to set that yourself:

acc.displayLocation = 'above'

acc.displayLocation

'above'

Our variable "acc" is the exact accidental that is attached to

the B-flat Note stored as bflat. It’s not a flat that’s similar to

B-flat’s flat, but the same one. (in computer-speak, acc is a

reference to .accidental). So now if we look at the

.displayLocation of bflat.pitch.accidental we see that it too is

set to the silly “above” position:

bflat.pitch.accidental.displayLocation

'above'

Python is one of those cool computer languages where if an object

doesn’t have a particular attribute but you think it should, you can add

it to the object (some people find that this makes objects messy, but I

don’t mind it). For what I hope are obvious reasons, the Note object

does not have an attribute called “wasWrittenByStockhausen”. So if

you try to access it, you’ll get an error:

bflat.wasWrittenByStockhausen

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-25-fbb7070911f6> in <module>

----> 1 bflat.wasWrittenByStockhausen

AttributeError: 'Note' object has no attribute 'wasWrittenByStockhausen'

But if you set the value of that weird attribute, you can use it later:

bflat.wasWrittenByStockhausen = True

f.wasWrittenByStockhausen = False

Then you can write an “if” statement to see if this is True or not:

if bflat.wasWrittenByStockhausen == True:

print("Hope you're enjoying Sirius!")

Hope you're enjoying Sirius!

Note that in the last line above you will need to put the spaces before the “print” command; Python uses spaces to keep track of what is inside of an if statement (or lots of other things) and what isn’t.

(If you don’t get the Stockhausen joke, see: wikipedia . )

Nothing will print for the note f since we set .wasWrittenByStockhausen to False:

if f.wasWrittenByStockhausen == True:

print("I love Helicopters!")

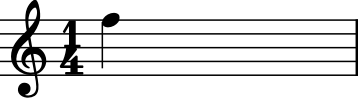

At this point you might be tired of all this programming and just want to see or play your damn note! If you’ve installed a MusicXML reader such as MuseScore, Finale, Sibelius, or Dorico, you can type:

f.show()

and see it. We make the default note length a quarter-note. We’ll get to

other note lengths in a minute. Notice that we put in a sensible clef

also, since otherwise you won’t know that this note really is F5.

If you want to hear it instead (and you’re on Windows or Unix or an older-Mac (10.5 or older)) type:

f.show('midi')

You may need to wait a few seconds when hitting play if you’re reading these docs online since the “grand piano” sound has to load and that’s about a megabyte long.

Maddeningly, Apple removed MIDI support in the version of QuickTime (QuickTime X) included in OS X 10.6 (Snow Leopard) and above (including Mountain Lion), so you’ll need to get the older QuickTime 7 from appleQuicktime to make that work. But as of OS X Catalina, even this no longer works.

When we typed f.octave we didn’t put any parentheses after it, but

when we call f.show() we always need to put parentheses after it,

even if there’s nothing in them (in which case, we’ll use the default

.show format, which is usually musicxml).

.show() is what’s called a method on the Note object, while

.octave is an attribute. Think of methods as like verbs (“O Note:

show thyself!”) while attributes are like adjectives that describe the

object. All methods need to have parentheses after them and inside the

parentheses you can usually put other things (“parameters”) that control

how to perform the action. For instance, let’s create a new note, D

by transposing our B-flat up a major-third (“M3”):

d = bflat.transpose("M3")

d

<music21.note.Note D>

bflat

<music21.note.Note B->

Instead of changing the original note, the transpose() method

“returns” (that is, spits out) a new note.Note object that

represents the operation of transposing it up (or down if you want to

try “-M3”) a certain interval.

If you want to change bflat itself, you can add “inPlace = True” to

the parameters of .transpose() separating it from the interval by a

comma. Let’s take it up a perfect fourth:

bflat.transpose("P4", inPlace=True)

bflat

<music21.note.Note E->

Of course now bflat is a terrible name for our variable! You could

type “eflat = bflat” and now you can call the note eflat. But

you’ll probably not need to do this too often. By the way, music21

handles some pretty wacky intervals, so if we go back to our variable

d (which is still a d – transposing bflat in place didn’t change

it; they’re not connected anymore, barely on speaking terms even), let’s

transpose it up a doubly-diminished sixth:

whatNoteIsThis = d.transpose('dd6')

whatNoteIsThis

<music21.note.Note B--->

B-triple-flat! Haven’t seen one of those in a while! Let’s check that

note’s .pitch.accidental.alter and its .pitch.accidental.name.

These are sub-sub-properties, meaning that they have three dots in them:

whatNoteIsThis.pitch.accidental.alter

-3.0

whatNoteIsThis.pitch.accidental.name

'triple-flat'

One last thing: not every note has an accidental. The d for instance

doesn’t have one, so it returns None, which is a special value that

puts nothing on the output.

d.pitch.accidental

If you want to be sure that it is None, you can print the value:

print(d.pitch.accidental)

None

Since d.accidental is None does this mean that

d.accidental.name is None too?

d.pitch.accidental.name

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-39-3f58fa9c100b> in <module>

----> 1 d.pitch.accidental.name

AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'name'

Nope! In fact it creates an error (which we’ll also call “raising an

Exception” for reasons that will become clear soon). That’s because

instead of getting an Accidental object from .accidental like we

did before, we got a NoneType object (i.e., None).

Accidental objects have an attribute called name, but the object

None doesn’t (it’s like trying .wasWrittenByStockhausen before

you’ve defined it as an attribute).

When you’re just typing in IDLE or the command line, raising an

Exception is no big deal, but when you’re running a program, Exceptions

will usually cause the program to crash (i.e., stop working). So we try

to make sure that our Notes actually have Accidentals before we

print the .accidental’s name, and we do that by using another

if statement:

if d.pitch.accidental is not None:

print(d.pitch.accidental.name)

This way is safer because we will only try to print

d.pitch.accidental.name if d.pitch.accidental is not None.

Since it is None in this case, Python will never try the second

line (which would otherwise cause it to crash).

If for some reason d did not have .pitch, we would need to test

to see if that was None before checking the subproperty to see if it

had an .pitch.accidental.

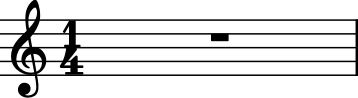

This might be a good place to take a rest for a second. So make a

Rest:

r = note.Rest()

Be sure to put the “()” (double parentheses) signs after note.Rest

otherwise strange things will happen (technically you get a reference to

the class note.Rest, which will come in handy in about 10 chapters,

but not right now).

You can .show() it as a ‘musicxml’ file of course…

r.show()

…but if you try to hear it as a ‘midi’ file, don’t expect to be

overwhelmed.

A Rest is an object type that does not have .pitch on it, so

naturally it doesn’t have .pitch.accidental either:

r.pitch

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-43-38156eec5526> in <module>

----> 1 r.pitch

AttributeError: 'Rest' object has no attribute 'pitch'

One last thing: notice that we never used a variable name called

“note” to store a note.Note object. Don’t do this. If you

type something like this (don’t type this if you want to continue typing

along with the user guide):

note = note.Note("C#3")

Well now you’re in a bind. You’ve got your Note object stored as

note, but we need the note module in order to create new

Note objects and now you have no way of getting it. (this is the

problem that “polluting the namespace” causes that your Python guru

friend might have warned you about). So unless you’re Amadeus’s

Emperor Joseph who complained that there were “too many notes,” you’re

probably going to want to make more note.Note objects in the future,

so don’t use note as a variable name. (The same goes with pitch,

scale, key, clef, and so on. You’ll see me use variable

names like myNote and myClef to avoid the problem).

Okay, now you have the basics of Note objects down, let’s go on to

Chapter 3: Pitches and Durations.