Fall

2000

![]()

Luminaries

Seven

notables contemplate the state of humanities, arts, and social sciences

at MIT and beyond.

![]()

![]()

Soundings is a publication of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT

Comments and questions to shass-www@mit.edu

Economics in MIT's fourth school

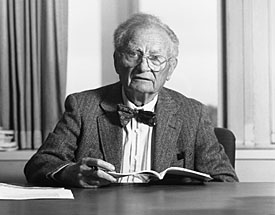

Photo:

Graham G. Ramsay

Paul A. Samuelson is Institute Professor of Economics Emeritus. He joined the MIT Faculty in 1940 and received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1970.

Before 1940, economics at MIT was an undergraduate service department. In the 1890s President Francis Walker, then America's most famous economist, taught the basic course that all engineers were required to take. Long-time department head Davis R. Dewey, brother to philosopher John Dewey, was our only well-known scholar. After he granted the business department (Course 15) its autonomous freedom, a small, tenured staff manned the two-semester junior year big economics course, aided by temporary assistants from Harvard and elsewhere.

By 1950, mirabile dictu, the MIT economics department had gained parity with Harvard, Chicago, Columbia and Berkeley—to say nothing of Cambridge, London and Oxford. How did this happen? Like the British Empire, our MIT graduate leviathan was created in a fit of absent-mindedness. That could not have happened at a Harvard where the doctrine prevailed: Every tub on its own (self-financed) bottom.

When I joined the ship in 1940, we were officially the Department of Economics and Social Sciences. Evidently, economics was not itself a social science! Some of my colleagues were psychologists, political scientists, anthropologists and personnel experts. Also statisticians. A sister department—a one-man department of "Humanics," which gave annually a lecture on human sex famous from Vassar to Wellesley to Yale—was temporarily merged into economics for administrative tidiness. Our benevolent dean was a retired diplomat who had been a Princeton classmate of President Karl Compton. Compton it was who turned MIT from the best engineering school in the world to the best place for science and engineering.

Operating as loose cannon on the deck was W. Rupert Maclaurin, son of the MIT president who had raised funds for our move from Boston to the big Cambridge buildings. Rupert inherited his father's green begging hand and President Karl Compton gave him a loose rein. Ralph Freeman, Rhodes Scholar and Canadian World War I artillery officer in the British Army, had absolute powers then as Head. By courtesy he deferred to our professional votes on new appointments and one by one we added stars to our team: Robert Bishop, E. Cary Brown, Charles Kindleberger, Morris Adelman, Max Millikan, Walt Rostow, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, Robert Solow, Evsey Domar, Franco Modigliani and other early tenured acquisitions, as if led by an Invisible Hand. Statistician Harold Freeman in the background guided our recruitment judgments.

The pivotal take-off came from our 1941 launching of a PhD program: Maclaurin money, plus extraordinary PR, drew from the opening year on scores of best qualified applicants—some of them, as it turned out, of future Nobel Prize caliber. By the middle 1960s, the Anti-Trust Division in the Justice Department was beginning to worry about MIT's garnering of a majority of all awarded National Science Foundation fellowships in economics.

Two factors explain our success. One, MIT's renaissance after World War II as a federally-supported research resource. Two, the mathematical revolution in macro- and micro-economic theory and statistics: this was overdue and inevitable—MIT was the logical place for it to flourish.

What was not inevitable was that the MIT Economics Department maintained throughout its explosive development a deserved reputation for collegial amiability.

![]()

Copyright © 2000 Massachusetts

Institute of Technology