Fall

2000

![]()

Luminaries

Seven

notables contemplate the state of humanities, arts, and social sciences

at MIT and beyond.

![]()

![]()

Soundings is a publication of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT

Comments and questions to shass-www@mit.edu

Well, I did it and I'm glad

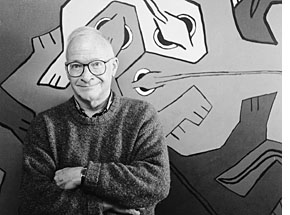

Photo:

Graham G. Ramsay

Travis Rhodes Merritt is Professor of Literature Emeritus. He joined the MIT Faculty in 1964, was Director of Course XXI from 1974 to 1986 and Dean for Undergraduate Academic Affairs from 1986 to 1996. He is presently Director of the Experimental Study Group.

For starters, a bit of quasi-apocryphal humor. When one of my sometime literature colleagues joined the School in the early 60's, he called his parents to give them the news. Asked what he'd be teaching here, he said "the Humanities." The phone connection was full of static. What his mother heard was "Amenities," which pleasured her genteel soul greatly. His dad, on the other hand, was sure he'd heard "Inanities."

My own case turned out to be less amusing, though no less telling. When my friends, family and ex-colleagues heard that I had accepted a job at MIT, most of them figured my work at a place commonly identified as "Tech" would have to be centered in teaching composition—as in business letters, research résumés and lab reports.

The truth of the matter, in part, was simply that I wanted to live and work in an urban setting. Greater Boston seemed to fill the bill perfectly. I'd had enough of "the sticks" (upstate New York; Williamstown, MA; Middletown, CT). The sole exception had been my three years of graduate work at the University of Chicago. So I turned down an offer from Dartmouth (too much like Williams). Harder to pass up was Boston College, until I learned that the Jesuit ambiance of the place might restrict my selection and treatment of texts, such as works by James Joyce.

So I joined MIT's School of Humanities and Social Science in 1964, inheriting in part the legacy of John Burchard, who had been Dean of the School since its founding in 1950.

During his years as Dean, Burchard had struggled mightily to consolidate instruction in the Humanities "Core," originally a four-semester sequence (reduced to two semesters in the early 60's) in which all entering MIT students focused their attention on a sequence of major Western texts. The objective was two-fold: to give all freshmen a set of readings that they might discuss together in whichever of MIT's 50+ living groups they might affiliate with; and to bring into the teaching of these texts an array of faculty, including not only those from the departments and sections of the School but also ambitious individuals from the Schools of Engineering, Architecture, Science and Management. The regular meetings of this core staff produced discussion of key ideas the likes of which I have not encountered since.

Class sizes were kept small enough (18–20 max) to make for classroom discussion, as opposed to "firehose" lecturing. All in all, the "community of discourse" ideal was well served by this arrangement. The experience was perhaps the most satisfying of any in my teaching career.

In recent years, the range of subject matter available to satisfy the HASS-D (originally HUM-D) requirement has proliferated impressively, and it is beyond question that this change has been, on balance, a change for the better.

Just one more thing: the eight-subject HASS requirement. Imagine, if you can, what life would be like for the legions of literature/language/history/philosophy majors at Ivy League and other "liberal-artsy" schools if they were required to complete eight (not three) courses in quantitative/technical/scientific fields as a part of their degree requirements. And we're supposed to be living in an "age of science"?!

Of course this distinction would be more palpable if, as a teacher and advisor to MIT freshmen, I did not so repeatedly hear from students something like this: "Well, that takes care of my Science Core requirements—the math, physics, chemistry, and biology. Now I suppose I've gotta pick a ‘Humanity' (sic). Which one? Well, which ones don't require too much work?"

Ah, irony!!!

![]()

Copyright © 2000 Massachusetts

Institute of Technology