Extra-Tropical Cyclone Formation and Energy Source

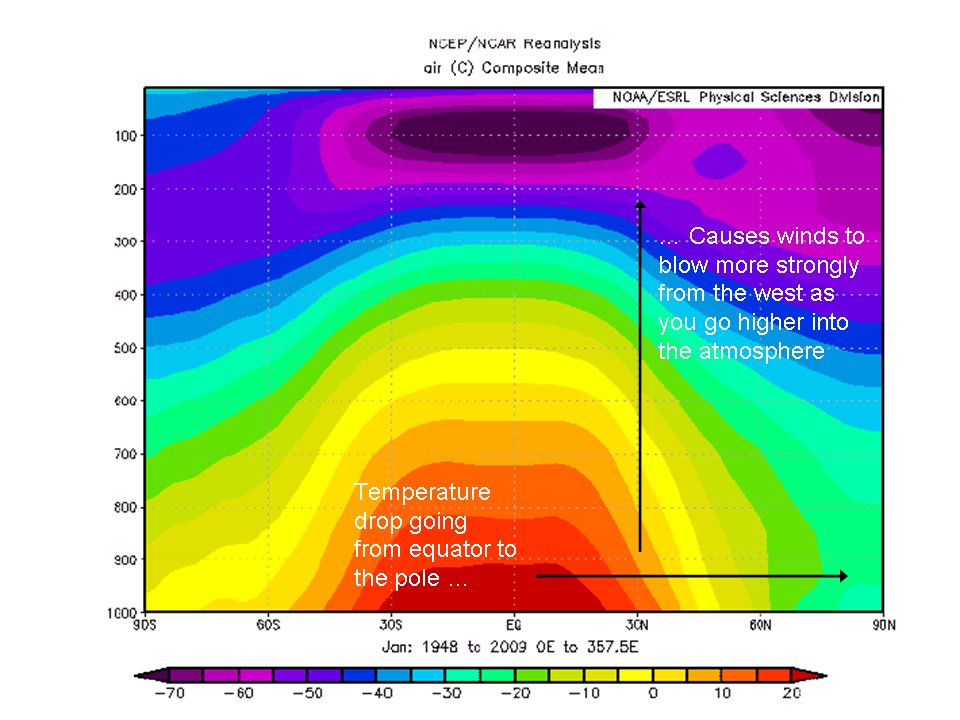

Where does the energy to produce these strong upper-level winds come from in an extra-tropical cyclone? Basically, strong upper-level winds are always present in the winter in mid-latitudes, because of temperature contrast between the equator and pole. January average temperatures are shown below in degrees C -- at the surface, temperatures in the tropics are over 70 degrees F, while temperatures near the pole average a frigid minus 20 F. These temperature contrasts lead to an average wind that blows from west to east, and increases with height. Extratropical cyclones get their energy from these sharp horizontal temperature (and moisture) differences between polar and tropical air. In the summer hemisphere, these temperature differences are greatly reduced, so extra-tropical storms tend to be much milder. This is a much different way of getting energy than the relatively uniform warm-water source that Tropical Cyclones feed off.

Image from MIT Course 12.307 webpage.

The rapid flow of air at upper levels in the mid-latitude atmosphere doesn't always move smoothly from west to east -- it often has strong waviness to it. We could see that in the upper-atmosphere map on the last page, and also in the map of wind and temperature below (at about 18000 feet, with temperatures in F -- it looks cold everywhere because it's so high up). There is a large wave in the movement of the atmosphere, with southward flow in the midwest, and northward flow along the east coast. Cold, polar air lies to the north of the wave, and warm, tropical air to the south. Along the east side of the wave, there is an exchange of warm and cold air -- flow across temperature contours. Again, this is quite different from the way tropical cyclones mix air -- in the tropical atmosphere, strong temperature gradients are only preset in the vertical, not the horizontal.

To understand how this storm system formed, we first need to go back in time a little bit, before the system was mature. Shown below is a map of the winds and the temperature of the atmopshere even higher up 12 hours earlier, showing 4 steps in how an upper-level wave in the wind pattern can cause a lower-level storm to form.

Below are two plots of how fast the atmosphere is spinning relative to the spin of the earth. The one with the black "L" is over 6 miles up in the atmosphere; the one with the red "L" is around 4000 feet. The upper-level spin in the atmosphere causes the lower-level spin to become stronger, so long as the lower-level spin is to the east of the upper-level spin. Since the upper-level atmosphere moves faster than the lower-level atmosphere, the upper-level low catches up to the lower-level low, and that's when the storm is strongest. After the two become aligned -- in the last panel of the animation -- the storm system begins to weaken.

If animations get out of synch, click refresh on your browser.