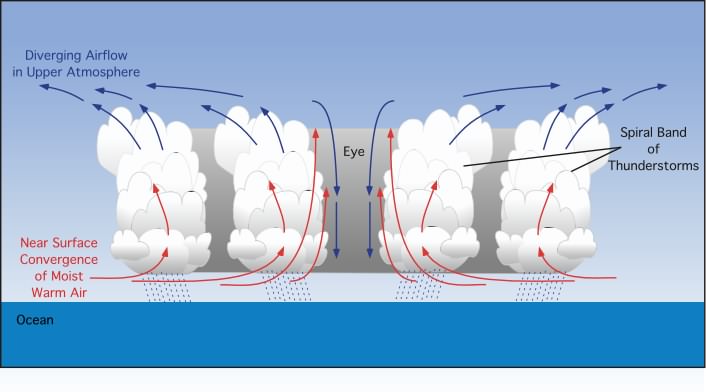

Cross-Sections of a Tropical Cyclone

It's interesting to look at cross-sections as well as maps of tropical cyclones, because they show a lot of the important structure of the storm. The diagram below shows how the air in the storm converges near the surface, and then diverges high up in the atmosphere. Lots of rain is formed by the water that condenses out of the rapidly rising air in a tropical cyclone.

Image from physicalgeography.net.

Below is an east-west cross-sectional diagram of Tropical Cyclone Lupit near peak strength. The strong circulation, especially at low levels, and the warmth near the center of the storm, can both be seen. Meteorologists often look at a quantity called "potential temperature", because they want to compare the energy content of the air, instead of just its temperature. Air a few miles up has a lot more gravitational potential energy than air at the surface. If you could convert all of the gravitational potential energy of air near the top of the diagram to thermal energy, the air would warm up to over 200 degrees F, even though its actual temperature is less than minus 100 degrees F! So the "potential temperature" is the temperature the air would have if you brought it down to sea level, using all of its gravitational potential energy to raise its temperature.

The vertical axis on the figure above is pressure, and sea-level pressure is about 1000 in the units shown. Pressure decreases by about a factor of 2 for every 3.5 miles you go up in the atmosphere shown here, so the top of the figure is about 14 miles high. Wind speeds are shown in miles per hour.

Another east-west cross section of the storm is shown above. This time we are looking at how fast the storm is spinning in different parts, as compared to the background spin rate of the earth. This quantity is an important number in meteorology because it tells you what sort of approximations you can make about a weather system. Near the center of the storm, the rotation of the storm is several times as large as the rotation of the earth.

This is a north-south cross section of the storm (north to the left), showing wind speed (mph) and potential temperature (degrees F). There's a lot of other stuff going on here besides the tropical cyclone! The area near the cyclone doesn't have very strongly sloped lines of potential temperature, but further north the air starts to get a lot colder at a given pressure level. And the winds are roaring high up in the atmosphere, over 130 mph! The background motion and temperature structure of the air to the north is a lot different, and storms that develop in that environment have a much different structure and pattern of evolution.