| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |

| Vol.

XVII No.

1 September/October 2004 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Teach Talk

Developing Musical Structures:

A Reflective Practicuum

[These comments are excerpted from a paper entitled, "The Development of Intuitive Musical Understanding: A Natural Experiment." Psychology of Music: January, 2003. http://www.sempre.org.uk/journal.html]

Over the years I have taught the music fundamentals course subscribing to the usual rule-based music theory practice. But recently, out of a sense of dissatisfaction, I redesigned the course, most simply to make it work better – more appropriate to students' largely untutored but none-the-less well-developed musical intuitions, and more responsive to students' active and self-motivating ways of learning.

As I saw it, there was a major problem with previous approaches to the fundamentals course: we have been asking students to begin with what we believed were the simplest kinds of elements, but we were actually confusing smallest elements with simplest elements.

We focused on these small, isolated, decontextualized pitch and duration elements partly because they are the easiest to define , and thus also the easiest to assess with respect to whether students have learned them or not. More important, the symbols that represent these elements are the tools of the trade for seasoned musicians – they are what we depend on for communicating with one another, for saying what we heard and for telling others what they should hear and play. But in doing so, we are not distinguishing between, on one hand, our own most familiar units of description , the notes shown in a score and our analytic categories, and on the other, our intuitive, contextual units of perception – those which we all, in fact, attend to in listening and making sense of the music all around us.

From everything I have learned so far, these "units of perception" are highly aggregated, contextually and functionally meaningful entities such as motives and phrases, their boundaries marking the landmarks, the goals of motion, as we follow the continuously unfolding performance of a composition. We don't listen to "notes" anymore than we listen to letters or even phonemes in following the unfolding of ideas in a lecture or a play.

It is not surprising, then, that students, often those who are best at improvising and playing by ear (as well as those who are best at improvising when making and fixing mechanical gadgets), are sometimes baffled and discouraged when we ask them to start out by listening for, looking at, and identifying the smallest, isolated objects. For in stressing isolated, de-contextualized objects to which our units of description refer – to measure and name objects in spite of where they happen and their changing structural function – we are asking students to put aside their most intimate ways of knowing.

The new course, called "Developing Musical Structures" (21M.113) perhaps surprisingly shows certain similarities with the innovations implemented by TEAL in physics (Belcher, MIT Faculty Newsletter , Vol. XVI No. 2, October/November 2003) and the comments of Warren Seering in mechanical engineering (Seering, MIT Faculty Newsletter , Vol. XVI No. 1, September 2003). For example, instead of starting with exercises drawn from canonical music theory, students begin by actually making music through composition projects aided by the computer music environment, Impromptu .

| Back to top |

Design Principles

Two very basic principles have guided the design of the course and the facilitating computer music environment, Impromptu . First, computers should be used only to do things we can't do better in some other way. Second (borrowed from Hal Abelson), an educational computer environment is valuable to the degree it causes its developers to re-think the structure of the relevant domain. Thus instead of saying, "Here is this computer with all these neat possibilities, what can I do with it?" I said, "Here are some things that beginning music students can do already, how can I use this intuitive know-how to help them learn to do what they can't yet do in a more musically relevant, intuitive, and accessible way?

Impromptu evolved in answer to these questions coupled with related issues of representation. Music notations represent music at the "note" level and I wanted to give beginning students more aggregated and perceptually meaningful elements. But "notes" are necessary to make them. So, I was drawn to the potential of the computer as an interactive medium because I could create programmable, clickable icons that would immediately play just such already aggregated melodic motives. These playable icons would function for beginning students in their initial composing projects as both units of perception and units of work. We called them tuneblocks.

The Working Environment

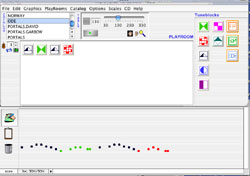

In the screen shot, the icons on the right, when clicked, play meaningful structural entities (motives); in this example, they include the motives with which to reconstruct the melody, "Ode to Joy." To build the melody, students drag tuneblocks into the Playroom and arrange them in order so that they play the whole melody.

Blocks 3-1-3-2, the opening two phrases, are shown in the Playroom. Notice that as students build up a melody, they are actually involved in "constructive analysis" – i.e., they are reconstructing the larger structure of the melody as embodied by the sequence of icons/motives. The graphics window at the bottom of the screen shows a more fine-grained representation of the sounding blocks – "pitch contour" graphics.

The most interesting work develops when students are given what they called "strange" blocks borrowed from unfamiliar pre-tonal or post-tonal styles. Students are asked to make a melody "that you like and that makes sense" by listening, arranging, and rearranging blocks in the Playroom window and also modifying the "contents" (pitch and rhythm) by "opening up" the blocks using the edit window. It turns out that almost everybody can do that. However, in any one class of 10 or so, given the same materials, no two students come in with the same tune.

Most important, students are asked to reflect on their process of composition as an integral part of the process, itself. As they work, students keep a log commenting on their decisions, and how this informs their emergent "model of a sensible tune." Students' papers, together with the performance of their compositions, become the center of our class discussions. Of course, students are often surprised, even confused, that the focus in class discussions is on their puzzlements and insights rather than on collecting notes drawn from the instructor's knowledge and information. Instead, as instructor, I am interrogating, probing, questioning – in order, collaboratively with the students, to make sense of and build on their sense-making.

The text, Developing Musical Intuitions (Bamberger, 2000) and recorded examples on an accompanying CD, illustrate how composers have used and extended some of the structural principles that are emergent in the students' own work. In addition to the conventions of notation and other vocabulary, the basics of music fundamentals are couched in terms of generalizable principles, thus informing encounters students have had in composing, listening critically to one another's work and to the recorded examples.

One of the gratifying results of the class is that instead of my devising questions to test what the students have learned, it is their continuing investigations into their own and one another's musical understanding that becomes the generative base for developing new knowledge. Searching for answers to questions that they have put to themselves, students begin to build a developing theory of musical coherence. At the same time, they are developing hearings and appreciations of music that go beyond what they know how to do already, to knowing about and knowing why . And in that process, they are also learning to hear and to notice aspects of music that previously passed them by, thus helping to broaden their musical taste and their listening preferences. Rather than giving up their intuitions, they learn in the service of better understanding them.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |