| Vol.

XX No.

2 November / December 2007 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

A White Paper on How MIT Should Think

About Institutional International Exchanges

MIT, like many internationally oriented universities, is discussing how to lead in an era where there are global economies and global collaborations. Like all modern research universities, MIT is dedicated to education and research. The research enterprise has long had strong international components. Increasingly, education is taking on more of a global flavor.

Given this more international flavor in education, MIT finds itself both wrestling with how to provide global experiences in its education and being approached by universities worldwide who want to partner in some educational fashion. The purpose of this paper is to elucidate the need for a globally oriented education, outline a value statement for our engagements, and lay out some of the principles by which MIT will engage.

The Need for a Globally Oriented Education

At MIT we are committed to continuing to provide an education which is grounded in science and technology that:

- Ignites a passion for learning,

- Provides the intellectual and personal foundations for future development, and

- Illuminates the breadth, depth, and diversity of human knowledge and experience,

in order to enable each student to develop a personal, coherent intellectual identity [Robert Silbey, Task Force on the Undergraduate Educational Commons, MIT (2006)]. The need for this kind of education is greater than ever.

At the same time that we are confronted with ongoing Big Problems in society, we find ourselves in a world where major parts are undergoing economic and cultural globalization. This is sometimes referred to as the “world is flat.” [Thomas Friedman, The World is Flat, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York (2005).] The global economic order is shifting before our eyes. The implications of this are profound.

Our graduates must be able to move seamlessly and add value in many different cultures while competing with people who may be willing to work for substantially less. As always, the answer in these situations is that our graduates must be able to innovate to add value for the good of society.

What is also clear is that science and engineering continue to evolve on a global scale. New technologies and scientific discoveries make for new products that engineers create all over the world. Witness the iPod, for example. In the area of biological engineering, there is much intellectual ferment that is bringing together biology and engineering in ways that create new systems for human beings. Further, the impact of millions of innovative users on the information superhighway is creating new opportunities for software engineering. In addition to new products, new lean processes have sprung up and engineers need to be able to understand and control these processes in predictable ways. Thus many products are now made through global supply chains which are themselves engineered. Finally, large-scale complex systems continue to be created. In some ways, science and engineering have never been as exciting as in this globally competitive world.

Our science- and technology-centric education of today and tomorrow needs to prepare our students to cope with all these emergent complexities. These challenges cannot be addressed by working only within national boundaries or by working only with people whose ideas about defining problems, organizing teams, recovering from failures, or measuring success are like their own. Instead, students need to develop an understanding and appreciation of the challenges inherent in participating in a global economy.

| Back to top |

Value Statement for a Globally Oriented Education

In light of this changing world, MIT wants to produce global leaders with global awareness. This will be accomplished on the basis of the mission and core values of MIT combined with clear definitions of the educational goals for our students.

Mission, Values, and Aspirations of MIT

The mission of MIT is to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the twenty-first century.

This mission is best served by having an international focus consistent with the core values and aspirations of MIT. These core values include:

- A commitment to a meritocracy

- High Quality (not doing everything but doing everything we do with quality)

- Mens et Manus (Mind and Hands)

- Service to mankind.

We are also affected by our culture and aspirations. We describe the culture as one of energetic entrepreneurialism with a deeply ingrained belief that there is great value that comes from “bumping” into each other. Thus, MIT is sometimes described as a modern day “Silk Road.” In this sense, MIT the place “02139” is very important. The co-mingling of the best faculty with the best students and staff in a physical location is one of the engagements that have made MIT well known. We also aspire to:

- Have others copy us (this is, after all, the essence of leadership)

- Collaborate with the world’s top universities to share and understand best practices.

Existing Opportunities for Global Education Abroad

In keeping with the spirit of MIT, many smaller-scale pilot programs have been set up. These provide proof of principles for a global educational experience and are the basis on which we can build. These opportunities fall into three classes. Opportunities which are based on work (internships or research), opportunities which are based on overseas education (either exchanges or unilateral study abroad), and opportunities which are based on public service abroad.

Existing opportunities include:

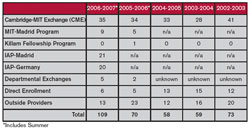

Internships: MISTI industry and research internships, G-Lab, departmental internships, DUSP-PSC internships, PHRJ internships (see M.I.T. Numbers for MISTI participation)

Research: International UROPs (IROP), DUSP, Architecture, RWTH-Materials exchange, Progetto Roberto Rocca (Italy), Consorzio Italia-MIT, MIT-France and MIT-Spain Seed Fund for collaborative research (see M.I.T. Numbers for IROP participation)

Public Service Learning: Public Service Center, D-Lab and other service learning courses, IDEAs competition, IDI, I-House

Study-Abroad Exchanges: The Cambridge-MIT Exchange, Oxford-MSE exchange, Architecture Delft and Hong Kong exchanges, Aero/Astro exchanges (click here for an overview of the Cambridge-MIT Exchange)

Unilateral Study-Abroad: MIT-Madrid, IAP language courses in Madrid and Germany, competitive foreign fellowships

MIT Goals for Global Education Opportunities

We want the students who take advantage of the Global Education Opportunities that we offer to:

- Return better than if they had stayed at MIT (with new skills and competencies specific to their global experience)

- Be stretched outside of their comfort zones and gain self-confidence and leadership skills

- Develop an international network of links that will serve them for years

- Not suffer any academic or financial penalty.

For MIT, the institution, we want to learn best practices and pedagogy from our educational international engagements and continue to be a leadership institution for others.

A recent EECS committee that was asked to address issues of global education concluded (March 2007): “The world facing our graduates is changing dramatically. We need to change the culture at MIT to make international engagement for students and faculty as pervasive as UROPs are for undergraduates.” This is a high goal, since currently we believe that approximately 20% of each class engages in some international experience while 85% engage in a UROP. We must also raise the resources so that all our students can participate in these engagements without financial barriers. This will mean additional resources so we are able to maintain our proud tradition of need-based aid.

| Back to top |

Principles for International Engagements

The MIT Faculty Policy Committee in 2005 laid down some principles for all MIT international engagements (education and research). These principles are designed to preserve the MIT name, protect the precious resource of faculty time, and ensure that we deliver with the highest quality. These principles are:

- The effort has to be “mission centric” to MIT’s focus in education and research. It should not be a service.

- The MIT name must be protected.

- Political and social sensitivities must be addressed.

- MIT should always stand by its policies relative to open access and information.

- MIT faculty must be clearly behind the effort in significant numbers for major projects.

- Each major effort must have an MIT officer/dean behind it, guaranteeing performance and delivery of expectations at the institutional level.

- The effort must be sustainable economically and intellectually.

- MIT does not outsource the granting of degrees (this ensures that only MIT guarantees quality).

- Significant international efforts should not detract from our ability to serve our students at MIT.

- Care is needed to make sure that activities do not create uneven loads on faculty not involved in the programs.

- Guidelines on pricing and costs are necessary.

Types of Global Engagements

A taxonomy for understanding the types of engagements we have is as follows:

- Research (i.e., the primary purpose of the engagement is addressing research questions)

- Work (i.e., the primary purpose is providing work experiences for our students)

- Education (i.e., the primary purpose of the engagement is providing an educational experience for students registered at MIT. This can include a service learning experience. This can also be subdivided into undergraduate and graduate engagements)

- Public Service Projects (i.e., the primary purpose is to improve the human condition in underdeveloped countries)

- Thematic (i.e., oriented around a theme such as energy or material science)

- General (i.e., not specific to any theme)

- Small (i.e., involving one or two faculty and a small number of students)

- Large (i.e., involving multiple faculty or multiple departments or tens of students)

- Minor (i.e., not involving MIT at the level of Academic Council. Usually this would be an engagement which is at the level of a department or lab or center or below, and usually is not at a senior level on the other side.)

- Major (i.e., involving a member of Academic Council. Usually this is a multi-department effort or is at a senior level on the other side [government or head of a university].)

The nature of an entrepreneurial institution like MIT is that there are many small thematic research-oriented international engagements. These are organized and supervised by the MIT faculty and are essential to a modern set of research engagements. MIT should have as many of these as the faculty desire and can maintain with quality. There is also a smaller set of large research collaborations. These are also very desirable. MIT must pay attention to all these engagements. However, since our undergraduates are the least mature of the groups participating in engagements, MIT must pay particular care to educational engagements, especially large, major undergraduate educational engagements. These have the potential to affect many students (with whom we have a duty of care) and, if things do not go well, to increase risk for MIT. Thus we turn to the principles that should govern large, major undergraduate educational engagements.

Principles for Study Abroad Exchanges

As we expand our international educational offerings, we are faced with a large number of possible choices of partners with whom to have an exchange. In general, we will only engage with the best universities in any country. The partners with whom we engage must have enough similarities for us to make a fruitful connection and enough differences for the exchange to be worthwhile for our students and us. The right partners can help MIT engage in certain issues (e.g., a thematic exchange around energy) and we can help our partners learn (e.g. help Cambridge University learn how to run undergraduate research programs).

The principles that should guide us are:

- The educational goals of an exchange must be clearly defined initially.

- MIT will only engage in a small number of large exchanges (typically fewer than three and diversity of exchanges is desirable).

- Exchanges must have a minimum size (probably 25 students per year) for institutional learning to take place.

- Exchanges must be with a high-quality institution so that students get comparable quality to MIT instruction (the best institutions in a country).

- Faculty connections associated with the exchange are highly desirable.

- MIT will preferably exchange with institutions that are different from MIT in ways such as courses, education system, learning style, contexts; so the exchange offers our students a different educational experience to reflect on their MIT experiences.

- MIT will only exchange with institutions where there are good and effective advising systems in place.

- Exchanges must be for a minimum of a semester, preferably for a year.

- Exchanges do not have to be symmetrical but should not be substantially advantageous to only one side.

- Exchanges will not be approved to places where there is substantial risk to our students.

- Students sent on exchanges should learn in the language of instruction of the other institution and take appropriate language courses before they leave.

- Exchanges must be consistent with Faculty Policy Committee guidelines.

- All exchanges will have a periodic review (3-5 years) and a graceful exit strategy.

Conclusion

The Task Force on the Undergraduate Education Commons called on MIT to shift its core education so as to be the premier undergraduate education for this century. It is now clear in this globalizing world that providing significant global educational opportunities for our students is one of the things we must do. Not to do so will shortchange our students and MIT for the future. The recently released report of the Global Educational Opportunities at MIT committee (GEOMIT) calls on us to increase by more than a factor of two the programs that we know work in the MIT context. These include programs such as MISTI, D-Lab, public service opportunities and international UROPs, as well as exchanges. Since a key part of this growth might come from exchanges, this paper has outlined a set of principles that MIT can use as a guide in considering which exchanges make sense for us.

The Office of the Dean for Undergraduate Education is committed to working with the programs, departments, and faculty to facilitate the desired growth in our current suite of global educational opportunities. We will help to provide the infrastructure as well as work to raise the resources necessary to make this sustainable in the MIT context.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |