| Vol.

XX No.

2 November / December 2007 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

The MIT Office of Admissions: Choosing the Best Candidates and Handling Them With Care

As the outstanding students in the class of 2011 settle into their lives as the newest members of MIT, I thought it would be a good time to provide you with a window into the process through which the Admissions Office brings our talented undergraduates to campus.

There are three phases to the undergraduate admissions cycle. First, we spend a significant amount of energy building the highest caliber pool of applicants. Second, we engage in a thorough, committee-based process to select those candidates who are best matched to an MIT education. Third, we look to convince the group of admitted students that MIT is the best choice for them. The goal of the entire process is to yield the very best incoming students – those who will take full advantage of, and contribute fully to, our very special community.

As I write this (October 2007), the Admissions staff is scattered across the country talking with as many students and parents as possible about the Institute. While it is true that most students are familiar with the MIT name, many of them are far less familiar with the “real” MIT – in other words, the reality of our culture, community, and people. In fact, we find that the conception that many students have about MIT is about a generation old. This makes sense – according to a study we did last year surveying high school students, the primary influence on a student’s college choice is his or her parents.

Last year I was visiting the Missouri Academy of Science, Math, and Computing, and a student actually asked me if there were any women at MIT. So we need to be out on the road pro-actively informing students about the current realities of MIT and correcting the false stereotypes that perpetuate.

We are clear about what MIT is and what it is not – we do not want to encourage students for whom MIT would not be a good fit. But there are many talented students who have both a central interest in math and science and the capacity and desire to make a real difference in the world who do not apply to MIT, simply because they don’t fully understand what we are about. And, while we have a strong Web presence – indeed, our Website (web.mit.edu/admissions) is often cited as the gold standard of Admissions Websites – we need to reach those students who might not make the effort to visit us online due to the mistaken thought that we’re worlds apart from what they’re looking for in a college.

Although the core culture at MIT has remained the same for many decades, things have certainly changed on campus in the last generation. Things have changed in the world as well. Nineteen percent of students entering MIT in 1977 reported being involved with some type of community service project or civic group. In the current freshman class, that number rises to 93%. A cynic might note that much of the community service in which students participate is required or forced upon them, and he or she would be right. But my view is not cynical. I think that just as a person’s behavior follows from his or her attitude, a young person’s attitude will follow from his or her behavior. The increase in community service projects among our applicants will lead to a generation of students more interested in making a difference in the world. (Witness, for example, the explosion in the number of students participating with the Public Service Center.)

We see this change all the time on the road. At one school I visited in Seattle this month, the head of the school talked to me about the school’s main focus of instilling in their students a mindset of service. While visiting a school in Portland, Oregon, I happened to be there on the day they had a service learning fair. In each of these cases I had the chance to talk with students, teachers, and school administrators about how central these things are at MIT, and seeing their heads nod with interest, as if this was news to them.

When we talk with students on the road, one of their foremost concerns is faculty-student interaction. They question this in many different ways, asking about average class size, research opportunities, and whether graduate students teach classes.

But what they really want to know is how likely it is that they will have close and meaningful contact with faculty.

This is highly valued and fortunately, with the enthusiasm that our faculty show in teaching and mentoring students in the classrooms and in the labs – notably through programs such as UROP and as freshman advisors – we have many good stories to tell.

| Back to top |

After the Admissions staff comes back to campus at the end of October, we will begin reading application files. Through the winter we will focus on reading the applications we receive and selecting the class. All faculty are invited to participate. Indeed, each year many faculty, including the faculty members of the Committee on Undergraduate Admissions and Financial Aid (CUAFA), read application folders and provide their inputs to the selection process. If you are interested in being part of this activity, please contact either Steve Graves (sgraves@mit.edu), the current chair of CUAFA, or me.

The process is rigorous and thorough. Admitted students pass through no fewer then five stages of evaluation, with the final selections all being done by multiple committees to ensure as fair a process as possible. All applications are read at least once, and many are read multiple times. The staff puts a great deal of energy into the process, reading the cases with great care, researching programs, and spending time on the phone and e-mail clarifying information with school counselors, teachers, and our alumni interviewers. We discuss, argue, and finally, make decisions.

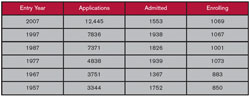

The process is quite difficult because we receive applications from so many more highly qualified candidates than we could possibly admit, more so now then ever before (see the table). And, while we look for students who show qualities that would make them a good match for MIT – academically talented students interested in an analytical-based, hands-on education, who have shown true engagement, initiative, curiosity, and community mindedness – there is no one specific profile of student that we are looking for. The students we admit will have a wide range of interests, activities, backgrounds, and experiences. And we value that.

Once we admit them, our job is far from done. We spend a great deal of energy connecting with the admitted students and fully informing them of the opportunities at MIT so they will make the best decision as to whether to choose to enroll. Because we chose them, we think that they are great matches for MIT and hope very much that they will, in turn, choose us. And many of them do.

Last year 69% of the students we admitted chose to enroll (our highest yield ever), and one of the highest yields in the country.

Of particular note is that students who visit campus once they have been admitted yield at an even higher rate: 81% last year. While some of this is selection bias (students who are more inclined to enroll are more inclined to visit), our surveys indicate that the campus visit – notably during Campus Preview Weekend – is a big reason students choose to enroll at MIT. Seeing first-hand how vibrant the atmosphere is on campus is enough to convince many of them that this is the place to be.

Personal interaction is supremely important in helping students feel connected to the campus community, and therefore make them more likely to choose to enroll. Here is another place where faculty can be helpful, and we would very much appreciate your participation. As I mentioned earlier in this article, students are very interested to know what kind of faculty interaction and research opportunities they will have. There is no better way for us to communicate this than directly through our faculty.

As the competition for these top students heats up – as other schools out there are now emphasizing science and engineering programs and recruiting the top students interested in those fields – we have to continue to communicate well the exciting opportunities that await these students at MIT, and how much we want them to join us.

There is a fair bit of work that goes into recruiting and selecting our remarkable student body. I cannot praise enough our talented and hardworking staff, who are completely committed to MIT, to its students, and to the ideals of a meritocratic, rigorous, and transparent process. But we also rely on literally thousands of others, from alumni who volunteer to do outreach and interview our applicants, to the current students, staff, and faculty who make countless connections with our prospective students, all in the service of bringing the best students who are well matched for us to campus. Something this important deserves nothing less.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |