| Vol.

XXIII No.

4 March / April 2011 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

From The Faculty Chair

Reinventing and Sustaining the Faculty of the Future

The recently released report on MIT Women in Science and Engineering celebrated the progress made since the original 1999 and 2002 reports, while cautioning that much work remains to be done. The progress is a tribute to the voice of faculty; in this case the MIT women faculty, who used data and personal experiences to call out inequities. It’s also a tribute to the good sense of MIT’s leaders who accepted responsibility for the problems and took actions to address them.

I open this column on this note not just to congratulate the community for its good work, but also to suggest that perhaps we should use this example to take a hard look at the future of our profession itself. I worry that some features of the faculty role are perhaps no longer well suited to recruiting and retaining the best and brightest talent needed to keep MIT and our peer institutions the beacons of innovation that the nation and the world need and will be willing to support.

The standard image of the faculty career is a lockstep sequence of movement from assistant to associate professor to tenure in eight or so years, followed by promotion to full professor several years later, and then a long sequence of teaching and research to retirement. That model no longer captures what most faculty do.

Research careers are incubated or aborted earlier and end later in life than in the past. Interests change, knowledge grows, and disciplines evolve faster than many faculty can keep up with over the full course of their careers. Most faculty spouses or partners are highly educated and employed professionals, so career choices and patterns are dual not singular decisions. Teaching technologies are changing in ways that are altering who, when, and how we teach. Retirement at the “normal” age is becoming an oxymoron.

Moreover, I believe societal forces will pose increasing challenges to the business model that supports traditional lockstep careers. Witness the current attacks on pensions, benefits, and tenure of elementary and secondary schoolteachers. Do we really believe universities will be left unscathed? Universities that fail to adapt to both the changing labor market and to increased scrutiny from families and taxpayers that buy their services may find the best and the brightest choosing other careers and parents and students turning to less costly educational alternatives.

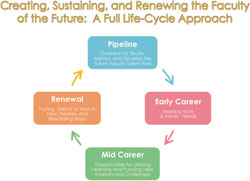

the Faculty of the Future: A Full

Life-Cycle Approach

(click on image to enlarge)

An alternative conception would be to take a life cycle model to our careers, one that better integrates professional work, personal, family, and community activities and that is punctuated periodically with time taken to renew our knowledge, develop new skills, and reallocate use of our time. Consider the following stages in the life cycle model depicted in the figure.

Pipeline

Last year’s report on Faculty Race and Diversity highlighted the need to reach out and expand the pipeline of young talented people motivated to pursue an academic career. This is essential to our efforts to attract more underrepresented minorities to MIT and to our peer institutions. MIT has a number of outreach programs on campus such as the Laureates and Leaders Program and many individual faculty members mentor undergraduates through UROPs and other research projects. Many of us have made appearances in local elementary and high schools to share our work and to motivate students to explore exciting issues in our fields. Some faculty have brought students who have surpassed what their high schools can offer into their labs, and served as mentors and showed these high potentials the excitement that comes from working on the frontiers of scientific discovery and problem solving. The wonders of online tools now make it more and more possible to bring university lectures and modular teaching into high school classes, thereby making for a smoother transition from high school to college.

All of these efforts need to become more integral parts of our professional responsibilities and careers. I will come back to this point when I discuss the renewal stage of the life cycle model below since it represents an opportunity to bring the university level expertise, mentoring, and teaching into our high schools, something that can only benefit our national education reform agenda as well as incubate the next generation faculty talent pool.

| Back to top |

Early Career

We now lose too many talented young people, and especially talented young women, to alternative careers, because academia has not adequately changed and invested to address the work and family challenges of young faculty. The updated Women in Science and Engineering reports both note the progress MIT has made on this front in the last decade with expanded day care facilities, tenure clock extensions, and time off for child care. But as the reports note, these are just first steps. More childcare support, either on campus or through specialized high quality child care providers, remains a top priority for young faculty women and men and for those involved in recruiting them. I would venture a guess that in the next decade universities competing for the best talent will be in a race to the top to see which institutions can offer the best opportunities for starting a career and nurturing a family. MIT will need to continue to invest resources to address this labor market imperative.

Reducing the loss of talent in the early career stages will require taking a hard look at that limbo role we call post-docs.

Post-doc time is lengthening in science and post-docs are beginning to become more common in engineering disciplines and departments. A naïve question might be: Are these really necessary developmental and screening opportunities or a source of relatively cheap apprentice labor? We ignore these trends at our own peril. Watch for increased unrest and/or pressures from post-docs to improve their lives and shorten their time in this role.

Mid Career

The need for lifelong learning is becoming more important for all occupations, including faculty. Faculty members need time and resources to retool their skills as knowledge advances in their chosen fields of study and/or as their interests expand or their careers carry them into new or allied areas of research, teaching, and professional service. Sabbaticals are the traditional means for meeting this need but they too come in lockstep seven-year, semester-long increments. Many of our faculty already go well beyond standard sabbaticals by taking time off to start businesses or work in industry or government. Some faculty spend time at other research or teaching institutions to be with spouses and families spread across the globe. The growing number of international partnerships are taking faculty to sister institutions. As we expand our role in mid career or executive education, more varied forms of teaching will be expected of faculty. The growing power of online learning technologies will mean that the best of our faculty will be teaching not just traditional MIT students on campus but their “classrooms” will have a global reach. Another prediction: If we don’t adapt our careers to reach out in these ways, our competitors (peers and other online teaching mills) will. Each of these departures from the standard career model illustrates the need for investment in mid-career retooling, and will continue to grow.

Renewal

Retirement is indeed becoming an oxymoron. Most of us are healthy enough and want to find ways to continue engaging in interesting and constructive professional activities and maintain a link to MIT well beyond the previously presumed retirement age. But we also want to make room to renew MIT with new recruits.

The standard model of buying out faculty with small financial incentives wastes money and doesn’t address the real interests of most faculty.

We need to better fund and support a new model of faculty renewal in which faculty transition from full-time teaching and research to a phased process of doing professionally rewarding work, perhaps in part at MIT and in part by putting their talents, wisdom, and experience to work in our communities, schools, private enterprises, and non-profit institutions. Imagine, for example, the contributions our senior colleagues would make if we encouraged and supported them in teaching and mentoring the young people we want to bring into the academic pipeline! That is just one example of how we can put our human capital to work as we gradually wind down our roles at the Institute.

These days I spend a good portion of my waking hours encouraging teachers and school district leaders to not just defend themselves against their critics and attackers but to be proactive in renewing the way they educate students, govern their schools, and reinvent the teaching profession. We should do no less. Now is our moment to get ahead of the curve by investing the resources and implementing the innovations needed to keep our profession sufficiently strong, respected, and rewarding to attract and retain the best and brightest talent and to retain the support of those who pay for our services.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |