| Vol.

XXX No.

5 May / June 2018 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Update From Washington

The Positive Near-Term Picture

for Federal Research Funding

To the surprise of many, 2018 has turned out to be a banner year for federal research funding thus far, and that appears likely to continue. This does not mean, of course, that more funding is not needed, or that the funding is adequate to meet all current demands; and some areas of research are in better shape than others. But despite the political polarization in Washington and around the country, the overall numbers for research increased significantly in fiscal 2018 and are likely to be sustained in fiscal 2019.

What happened, and why?

First, let’s look at the current fiscal year, which began last October 1. For the first six months of the fiscal year, funding was held to the previous year’s levels, as stalemate in Washington kept Congress from doing anything on appropriations besides allowing agencies to limp along at prior spending levels. But the stalemate broke in late February, and on March 23, President Trump signed into law a bipartisan omnibus appropriations bill providing funding for all federal agencies through September 30.

(President Trump provided a last-minute burst of uncertainty when he suddenly threatened to veto the measure over immigration and other matters – even though White House staff had been part of the negotiations on the bipartisan measure. But alarmed Congressional leaders convinced him to stand down.)

What happened to research spending?

The omnibus turned out to be a boon for science and engineering funding: Research spending will hit an all-time high in inflation-adjusted dollars. Basic and applied research are increased by more than 10 percent. The year-over-year percentage increase in research spending is the highest since fiscal 2009, a year that included one-time emergency stimulus money to counter the Great Recession. The last time research received such a large percentage increase before that was fiscal 2001, in the midst of the effort to double the budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

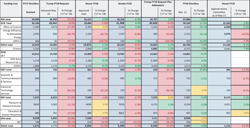

Not surprisingly, NIH – long a Congressional favorite – fares well under the omnibus, with an 8.7 percent increase, but so does the Department of Energy (DOE), the home of applied research programs that conservatives have tried to limit since the Reagan Administration and a target of the Trump Administration. The omnibus provides an increase of more than 12 percent for DOE, with its research programs doing even better (in percentage terms). (See table.)

(click on image to enlarge)

Why did things turn out so well?

The key to this happy outcome was the bipartisan agreement earlier this year to increase the spending caps on discretionary spending. What the research community often fails to appreciate is that the primary determinant of the federal spending level for research is the size of the overall federal spending pie. In a bill President Trump signed into law in February, Congress raised the amount of money available for non-defense spending in fiscal 2018 by almost 12 percent and the amount available for defense spending by about 14 percent.

Once Congress reached that deal after playing a game of “chicken” for months, research was likely to fare well. For decades, research and development has received a relatively steady share of total federal discretionary spending, and this year was no exception, with R&D spending rising in parallel with overall spending.

Put another way, no one on either side of the aisle, or on either end of Pennsylvania Avenue, was gunning for research programs. With the significant exception of proposed cuts in environmental research and applied energy research, proposals to reduce science funding were driven by the macro budget numbers, not by any antipathy toward the programs. (Democrats, in the end, were able to limit the damage to environmental programs, and Democrats were joined by some key Republicans, especially in the Senate, in protecting the energy efforts.)

The increase in the spending caps enacted in February – an amendment to a 2011 law to rein in spending to reduce the deficit – was a bipartisan agreement. Both Republicans and Democrats had thought the limits on defense spending were too low, but partisan disputes over non-defense spending had held up agreement. Democrats argued that the non-defense caps should be raised by the same amount as defense. Since Democratic votes are needed to get any spending bill through the Senate, the final agreement on the caps included a significant, though not equal, increase for both defense and non-defense spending.

Note that these agreements just concern discretionary spending, which Congress allocates annually through appropriations bills. By far, the larger portion (more than 60 percent) of the budget is mandatory spending – Social Security, Medicare, other entitlement programs – which Congress can change only by changing the laws governing those programs (as opposed to setting spending levels). Another aspect of mandatory spending is interest on the national debt (about 6 percent of the budget), which can’t be changed without the U.S. reneging on its financial obligations.

So what explains the variation in spending increases among the agencies?

The final fiscal 2018 numbers for each agency vary depending on the politics of the specific programs and the way Congress divvies up the spending pie among appropriations categories – an arcane process that reflects everything from overall spending priorities to the power of individual appropriations members.

But certain patterns have been stable over time. NIH is a bipartisan favorite – because the value of improving health is widely understood, as is the link between research and clinical advances.

NIH research is also supported by groups outside the research community, such as those focused on specific diseases, and members of Congress view funding NIH as something constituents understand. The National Science Foundation tends to get smaller but steadier increases that reflect overall support for basic research. DOE spending has become a political commitment for some Democrats, and some key Senate Republicans also watch out for the agency. The Environmental Protection Agency has become more of an ideological football. The amount of money allocated to early-stage research in the Defense Department tends to oscillate.

What’s the outlook for future spending?

Congress has now begun to write the bills that will set spending levels for fiscal 2019, which begins October 1. Importantly, Republican leaders have decided to stick to the February agreement on spending caps that covered fiscal 2019 as well as this fiscal year. (Initially, some House conservatives were interested in taking a new look at the numbers.) The fiscal 2019 caps provide a small increase over fiscal 2018 spending, so research spending is likely to hold steady, even after accounting for inflation, or see a slight increase.

President Trump’s budget proposal for fiscal 2019, released in February, was better for science overall than his fiscal 2018 proposal because of the additional money made available by raising the caps.

But Congress will end up being more generous for two reasons. First, the White House proposed to spend only part of the increase in the non-defense spending pie, but Congress will allocate all of it. Second, the Administration budget still targets programs the White House dislikes – such as some energy and environmental programs – that Congress will support. That’s already the pattern emerging in the first fiscal 2019 bills.

So it looks like continuity will be the name of the game, as many in Congress want to avoid new spending battles going into the 2018 elections, when party control of the Congress – particularly the House – is up for grabs. Initially, the betting was that Congress would not complete work on appropriations until after the elections, but it now seems possible (if not likely) that for the first time in decades, Congress could have spending in place by September 30.

| Back to top |

What about after next year?

After fiscal 2019, the outlook is murky and treacherous. Without further Congressional action, the spending caps in the 2011 law will come back into effect, causing discretionary spending to plummet. It’s impossible to predict what the political and economic situation will look like at that point. But the federal deficit will likely be on the rise significantly because of raising the spending caps and, most economists believe, because of the massive tax law enacted in December.

If the deficit once again becomes an issue and Congress remains too divided to reach any deals on mandatory spending, then discretionary spending will come under severe pressure.

Other issues could also complicate the overall political environment for research spending and higher education. Surveys continue to show strong and steady public support for science, but political polarization over issues like climate change could at some point start eroding that. And antipathy toward elite research institutions – demonstrated by the new tax on university endowments – is also something to watch (and combat). But the biggest concern remains the overall fiscal situation.

What has MIT done about all this and what will it do?

MIT has continued to work closely with the Association of American Universities and the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities to make the argument for federal research spending. President Reif and Vice President Zuber have met and are continuing to meet with White House and Congressional officials to press the case. The MIT Washington Office is working not only to raise overall funding for R&D, but has worked with faculty to hammer home the need for funding for specific areas of concern, including fusion and specific NASA projects.

Notably, White House and Congressional budget documents have mentioned growing competition with China, including in Artificial Intelligence, as one reason that U.S. research spending needs to remain strong. So at least some of our arguments are registering.

If you have any general questions about federal spending (or other federal policies) or if you need help with specific spending or policies, please contact me at dgoldsto@mit.edu or call the MIT DC office at 202-789-1828. We also put out a weekly news update. Please let us know if you would like to receive that.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |