|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Since the 1960s, cities in developing countries have faced an unprecedented rate of urbanization and increasing poverty. Uncontrolled proliferation of slums was the result. In general, these unplanned and under served neighborhoods are occupied by squatters without legal recognition or rights. The populations of slums lack the most basic municipal services, such as water supply, sanitation, waste collection or infrastructure, and thus are exposed to disease, crime and natural disasters. Governments have tried to deal with this problem in different ways. However, their urban policies often failed because of bad governance, corruption, inappropriate regulation, dysfunctional land markets, and, above all, an absence of political will. One response to prevent augmenting urban poverty involved the relocation of residents to resettlement sites that were usually outside of the city. Yet, slums emerged in city centers because these were places where the poor can find work more easily. Consequently, moving the people or replacing their physical facilities did not work well. Governments not only had to spend resources clearing slums and resettling inhabitants, but also later had to finance public transportation to facilitate access to employment in the central city. (See: Housing Priorities) A second approach was clearance and redevelopment. It meant temporarily moving the slum residents, clearing the land and building new housing for them on the same site. High-rise buildings are often proposed in order to house more people. However, experiences have shown that the residential density of a high-rise development is not much greater than that of a central city slum community. In addition to that, high-rise developments do not provide much ground-level space for low-income families to operate small businesses which these families need to supplement their incomes. The alternative to moving people or replacing their homes is upgrading. Upgrading consists of improving the existing infrastructure, e.g. water reticulation, sanitation, storm drainage and electricity, up to a satisfactory standard. Usually upgrading does not involve home construction, since the residents can do this themselves, but instead offers optional loans for home improvements. Further actions include the removal of environmental hazards, providing incentives for community management and maintenance, as well as the construction of clinics and schools. An essential part of upgrading is transferring tenure rights to the occupants at prices they can afford. The security provided by transferring these tenure rights has been shown to motivate occupants to invest two to four times the amount of funds that the government invests in infrastructure improvements in a slum area. Upgrading has significant advantages; it is not only an affordable alternative to clearance and relocation (which cost up to 10 times more than upgrading), but it minimizes as well the disturbance to the social and economic life of the community. The results of upgrading are highly visible, immediate and make a significant difference in the quality of life of the urban poor. |

Lima, Peru. Squatter invasion.

Penang, Malaysia. Relocation.

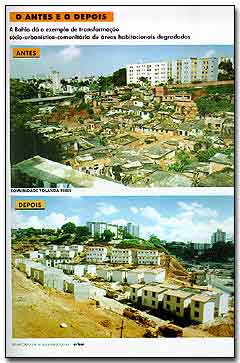

Comunidade Yolanda Pires, Brazil. |

||||||||||||

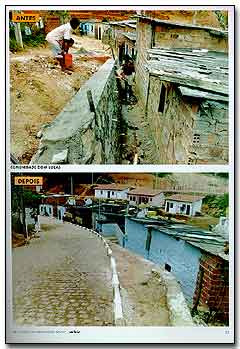

Dom Lucas, Brazil. Upgrading. |

Why the strong interest now in slum upgrading projects?Surveys have indicated a high level of demand and strong support for urban upgrading. In many countries there has been a dramatic shift in governance with local governments taking greater responsibility for the provision of municipal services. With democratization local governments are able to respond more effectively to the needs of their population. The local government has more power and is more interested in what happens in slums given the increasing voting power of poor communities. A strong NGO sector is now in place and works more effectively with government. Slum communities are often politically mature and able and willing to pay for services. It is also clear that with economic growth, in many economies, the disparities between the haves and the have-nots is increasing. The lack of basic environmental services in rapidly growing, dense urban and periurban settlements have resulted in public health and safety hazards. Programs to enfranchise the urban poor have high social priority. |

||||||||||||

What lessons have been learned about the past 25 years of upgrading?The World Bank, the regional development banks, the United Nations (Habitat, UNICEF, UNDP and ILO, in particular), most bilateral donors including CIDA, DFID, French development cooperation, GTZ, SIDA, Italian aid, and USAID; and thousands of NGOs and community groups have gained considerable experience over the last 25 years in implementing projects designed to upgrade slums worldwide. A large number of these projects have successfully demonstrated that slums and the lives of their residents can be improved. Some of these lessons are:

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||