Written by Polina

Bakhteiarov

New Orleans’

unique culture and

traditions constitute one of the most important reasons for why the

city should

be rebuilt and preserved. The multi-layered history of New Orleans was

derived

from the city’s initial function as the major slave trade port of the

United

States, which brought in countless Africans, many of whom remained in

the city

as both slaves, and eventually, free men and women. Today’s traditions

of

NOLA’s neighborhoods grew out of the customs of this wide variety of

people in

the late 1800’s. The city established its own style of food,

storytelling, and

religious ceremonies because its population was so diverse and unique,

unmatched by that of any other American city. Below, we consider just

some of

the cultural aspects that are vital to the spirit of New Orleans.

Parades

and festivals

New Orleans is

known

domestically and internationally as the “city of festivals,” with the

most

famous parade of all being Mardi Gras, or “Fat Tuesday.”

picture

from:

http://www.asergeev.com/pictures/archives/2006/504/jpeg/13.jpg

picture

from:

http://www.asergeev.com/pictures/archives/2006/504/jpeg/13.jpg

No

one can exactly

pinpoint the birthdate of this gigantic carnival because it formulated

as a

hybrid of multiple festivities that had been taking place throughout

the city

since its Westernization began in the 18th century. The

French had

been hosting masked balls and carnivals in New Orleans since as early

as 1718,

and they continued to do so until these festivities were banned by the

Spanish,

but later reinstated by the Americans in 1827 (Mardi Gras History,

2006).

Mardi

Gras is essentially comprised of a collection of “krewes,” or

bands of people, who construct their own floats and/or organize

themselves to

parade during the festival (this also applies to the other carnivals of

NOLA).

The first krewe, formed in 1857, was called the Mystick Krewe of Comus,

and, in

essence, single-handedly initiated the tradition of Mardi Gras, since

the

second krewe – the Krewe of Rex – was not established until 1872.

Today, the

massive parade entails everything from beads to masks to culinary

specialties

like King Cake (Mardi Gras History, 2006).

And

yet, there are numerous other festivals that might be less well

known to outsiders but are just as important to the people of New Orleans.

They include events such as the

Jazz Fest and Heritage Festival, pictured below.

Picture from: www.purplemoon.com

Picture from: www.purplemoon.com

This festival showcases

a

mixture of local and national music talents and is essential to the

preservation of New Orleans’

indigenous musical culture. Featuring famous acts like Bob Dylan, Paul

Simon,

Dave Matthews, Fats Domino, the Meters, Dr. John, Yolanda Adams, Elvis

Costello, the Rebirth Brass Band and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band,

Jazz Fest

is also a folk festival that is the perfect platform upon which local

talent

can showcase their compositions. In addition, there are numerous other

parades

and carnivals that occur during carnival season, such as Festival

National

(celebrating Francophile culture), Ponchatoula Strawberry Festival,

French

Quarter Festival, and the New Orleans Wine and Food Experience, just to

name a

few (New Orleans Spring Festivals 2006, 2006).

Food

New Orleans is the only

metropolis in the world that can claim to have conceived its own style

of food.

Both Creole and Cajun meals originated in the city, and are actually,

to many

people’s surprise, not interchangeable. The

Creole style of cooking, founded in the heart of New

Orleans at the turn of the 18th

century, was first

adopted by freed and enslaved Blacks, and, over time, became the

preferred

style of food preparation for people of a multiracial background,

including

African, Caribbean, European, and

Native

American. Creole cuisine has been passed down through generations as a

concoction of “iron-pot delicacies” that require ingredients that are

inexpensive and easily accessible, such as rice, greens, and chicken

giblets,

but that result in a delicious meal.

http://www.frenchquarter.com/s_images/city_food.jpg

Cajun gastronomy, on

the other hand, developed from the decedents of

Acadian (later called “Cajun”) exiles, who began arriving in New Orleans

around the 1760’s. Forced into

permanent isolation from their native land, the Acadians tried to

retain their

culture as much as they could and food was one of the means by which

they could

accomplish this. While Creole cooking mixed many different styles,

Cajun

cuisine was tailored to include ingredients that could easily be grown

in the

Nova Scotian climate (that of the Cajuns’ native land) and since most

of these

deportees were farmers, their cooking center around root vegetables,

corn, and

meat from livestock. Over time, these two cooking cultures blended

together to

form what today is known as “South Louisiana cuisine,” which is most

famous for

crawfish and gumbo dishes (Food, 2006).

Music

Not

only did New Orleans

birth a new

style of food, but it is also the founding place of the only indigenous

American music – jazz. Renowned musicians such as cornet player, Buddy

Bolden,

soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet, and the world famous trumpeter Louis

Armstrong all called New

Orleans

home. Jazz is truly a byproduct of the cultural history of New Orleans, since it came about from the influx

of European, African,

and Caribbean music that settlers and

slaves

brought with them to NOLA during the 18th century; these

different

styles became permanently mixed as more Blacks were freed and the

population of

multiracial people grew throughout the city. Fueled by the relaxed,

liberal

attitude of the city, this fusion of music came to be known as jazz.

http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/41616000/jpg/_41616520_jazzplayers_ap.jpg

The music style of

jazz originated from many different traditions that

the Blacks, Germans, Irish, and Italians settling in uptown New Orleans

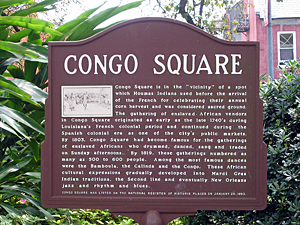

introduced into the city. The

“Creoles of color,” who were extremely skilled musicians of both

African and

European heritage, brought their professionalism. African slaves

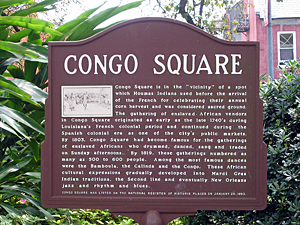

introduced New

Orleans to African drumming and dancing, a tradition that, even as

slaves, they

upheld every Sunday, gathering in what came to be known as Congo

Square, which

is located across Rampart Street, just behind the French Quarter.

http://freelargephotos.com/000316_s.jpg

After the dancing in

Congo Square was shut down during the Civil War,

Blacks began to organize in “gangs of Mardi Gras Indians;” they would

paint

their faces in the style of the Native Americans and parade through the

streets, challenging rival gangs to battles of strength. Sure enough,

these

shows consisted of call-and-response chanting, as well as drumming,

both of

which evolved from West African and Caribbean

cultures. Finally, at the close of the 19th century,

syncopated

music, such as the cakewalk and the minstrel tune, the roots for which

originated in Black communities, became the craze of the nation, and

the seeds

of jazz were planted (Jazz History, 2006).

Burial

Traditions

A unique aspect of New

Orleans culture surrounds the city’s

method of burying the dead. NOLA is quite famous for the “jazz

funeral,” which

is a lavish extravagance that, unfortunately and ironically, the poor

of the

city never get to experience until it is being held for themselves.

Furthermore,

Blacks in New Orleans

were never allowed to hold jazz funerals until the 1970’s, which was

just one

way in which this significant subpopulation’s culture was stifled.

However, in

the past 35 years, jazz funerals have gained great popularity and have

evolved

to include a larger parade of people and more modern music.

The funeral is

broken up into two parts: the “somber journey” to the

cemetery and the jubilant return from it. According to tradition, the

brass

band arrives at the place where family and friends are paying their

respects to

the deceased (usually in a funeral parlor or church) and the musical

ensemble

leads a solemn procession of mourners through the streets, playing

traditionally Black Protestant hymns, such as “Just a Closer Walk With

Thee.”

At the head of the march is the grand marshal, who is either part of

the band

or of the social club of the departed; this figure sets the grave mood

of the

procession by dressing all in black, holding his black hat in his

hands, and,

with his head up high, marching slowly to the graveyard. If the family

can

afford it, the open casket is pulled by a horse-drawn carriage.

http://images.scripting.com/archiveScriptingCom/2005/08/31/fullJazzFuneral.jpg

After the deceased

has been laid to rest, the band

guides the march

away from the grave, and once everyone is a respectable distance from

the site,

the lead trumpeter gives a two-note signal to the percussionists begin

to play

the “second line” beat, an indication that the celebration is about to

start.

The grievers open gorgeously-decorated umbrellas and fall in line with

the band

as everyone begins to perform the strut-like dance called the “booty

bounce” to

the music of songs such as “Didn’t He Ramble,” As the now festive

parade returns

from the graveyard, the joyous music alerts the neighbors of the

impending

celebration and the dancing grand marshal among the second-liners

serves as

assurance “that another soul has gone on home” (Marsalis, 1998).

picture

from:

http://www.asergeev.com/pictures/archives/2006/504/jpeg/13.jpg

picture

from:

http://www.asergeev.com/pictures/archives/2006/504/jpeg/13.jpg Picture from: www.purplemoon.com

Picture from: www.purplemoon.com