|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The City of New Orleans was originally

founded due to its

prime location at the mouth of the Mississippi River. In essence, it

provided an entryway to the far-reaching joint Mississippi-Missouri

River

system. For this reason, during the 18th and 19th

centuries, it was

eagerly sought after by major European nations who understood the

enormous

economic potential of establishing a port at such a prime location.

Historical records show that the first

European surveyor to

explore the territory of present-day Louisiana was Spanish conquistador

Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, who led an

excursion through the area in 1528. The first Frenchmen to land in the

area

arrived in 1682, led by René-Robert

Cavelier Sieur de La Salle, who claimed all of the area that is drained

by the

Mississippi River for France in the name of King Louis XIV. He

appropriately

named his claim “Louisiana” (Louisiana, 2001-05).

New Orleans itself,

however, was not established until 1717, when John Law’s Company of the

West,

which had gained full commercial privileges to Louisiana that same year

from

Antoine Crozat, made the decision to establish a “port of deposit,” or

“transshipment center,” at the mouth of the Mississippi River, calling

it “Nouvelle-Orléans” in honor of Philippe

II,

duc d’Orléans, a region that lies to the south of Paris.

Jean-Baptiste le Moyne

de Bienville, who initially proposed the erection of the city, foresaw

New

Orleans as a vital checkpoint along the Mississippi River trade route

and

envisioned the city as a hotspot for financial profit from the

substantial

quantities of goods traveling up and down the river

(New Orleans, 2006).

Nonetheless,

problems with the actual construction of the city began almost

immediately. Two brutal hurricanes struck the region in

1721 and

1722, destroying much of the city’s new architecture. Other delays in

the

building process centered around a lack of adequate tools, the

utilization of

unmotivated prisoners as the principal work force, and the humid, wet,

mosquito-dominated natural environment in which they were forced to

toil. In

the end, the Vieux Carré, or French Quarter, was established on

the banks of

the Mississippi, and the capital of the colony was relocated there in

1722 (“New

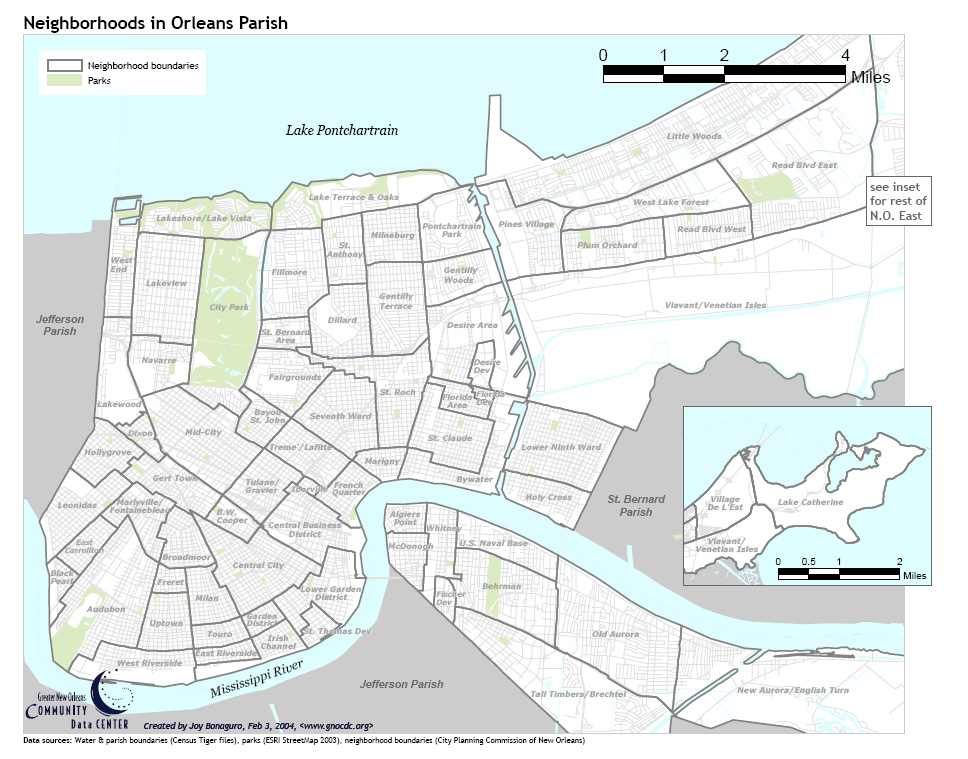

Orleans,” 2001-05). To compare the size of New Orleans in 1722 to its

current

size, please refer to the map below, where the Vieux Carré is

labeled as the

“French Quarter:”

From the time of the

city’s establishment in the 18th century, its demographics

have

always been heterogeneous. In 1721, New Orleans’ population stood at

just under

500 people, of whom 59% were white, 37% were Black slaves, and 4% were

Native American

slaves (New Orleans, 2006). By 2005, the city swelled to 454,863

people, of whom approximately 28% were White, 68% were Black, and only

.2% were Native American (New Orleans city, Louisiana, 2005). Whatever

the exact numbers

may be

now and were back then, it is important to realize that the history of

New

Orleans sprung up from a mixture of different cultures

that

have had to coexist in a physically unstable environment.

The main reason for

New Orleans’ perpetual racial diversity stems from the fact that, upon

its

founding, it immediately became the largest slave port in North

America. Aside

from the revenues brought in by commercial shipping, the city thrived

on the

earnings of sugar plantations that succeeded solely due to the manual

labor of

enslaved Blacks. Furthermore, in 1805, the City Council coerced

prisoners and

slaves into work chain gangs that basically built up the entire

municipality, toiling on projects such as the erection of levees and

public

buildings, as

well as the beautification of streets. Essentially, the entire City of

New

Orleans was built up and expanded due to an extensive exploitation of

Black

enslaved peoples, resulting in what historian Walter Johnson calls

millions of

“social deaths” as innocent Blacks were maliciously torn from

their

families and forced to work endlessly and live vacantly without any

sense of

community or history. While at the same time, they were being

forced into providing rich whites with hundreds of

billions of

dollars in hard labor (Lavelle, K., & Feagin, J., 2006).

The

French, the Spanish, and

the Americans

From the

establishment of the city by the French in 1717, to its sale to the

Americans

during the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, New Orleans and Louisiana traded

hands

between the French and the Spanish on several occasions, each time in

secret.

In the year prior to the Treaty of Paris of 1763, France furtively

relinquished

its colony to Spain in an enthusiastic attempt to rid itself of the

successive

economic failures of Louisiana. Less than half of a century later,

Spain

clandestinely returned the land to Napoleon, who almost immediately

sold it to

Jefferson. In fact, the ceremonies that occurred when Louisiana

was

handed over to France and then to America occurred in the heart of New

Orleans

at the Place d’Armes, or Plaza d’Armas, now called Jackson Square after

General

Jackson, who (although unnecessarily, since the War of 1812 had already

ended)

defeated the British in 1815 and successfully protected the city (New

Orleans,

2006). To take a virtual panoramic tour of Jackson square, please click

on the

following link: http://www.atneworleans.com/body/qt-jackson-square.htm.

Prosperity

and Hardship

From the 1820’s to

the 1850’s, New Orleans grew in area, population, and wealth, as money

poured

in from both agriculture (growing cotton, tobacco, indigo, rice, and

various

vegetables) and commerce. The city

became a major cotton port for the

Aside from battling

a debt of $24 million (in the 1880’s), New Orleans also faced the

recurring outbreaks of yellow fever, the worst of which occurred in

1853 (however, they continued until 1906, when the disease was finally

wiped out). Unfortunately, even with a more healthy population,

New Orleans was

never

able to fully recover from the economic blows of the Civil War (New

Orleans,

2006). With the enactment of the Jim Crow laws in 1890, virtually all

of the

power in the city went to white supremacists who degraded

Decline

during the Twentieth

Century

The

percentage of African Americans in the city continued to rise through

the first

half of

the twentieth century while the primarily Caucasian upper class

relocated to the outlying suburbs. This “white flight” began

after the

end of World War II and continued well into the 1960’s, when city

officials

tried to integrate New Orleans’ public schools for the first

time. This drove

even more whites out of the city in a migration that mirrored similar

ones in

almost every major American city and left New Orleans more

impoverished than

ever before. The urban renewal projects of the 1950’s and 60’s did

nothing for

the economy and only drove many educated, artistic black families from

the

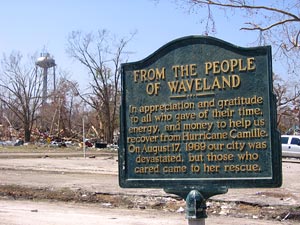

central neighborhoods into New Orleans East. To top it off, at the end

of the

troublesome decade in 1969, Hurricane Camille tore through the city,

destroying

buildings and claiming almost 150 lives in Louisiana and

Mississippi. Below, a

plaque in

New Orleans did

witness a slight rise in its economy during the oil boom of the 1970’s,

as

businesses invested in the city’s infrastructure. However, by the time

of the

World’s Fair of 1983, speculators had lost interest in the city and the

economy

had begun to crumple once more. Even the legalization of gambling in

1992 could

not jump start the economy and the city’s population began to slowly

decline by

the end of the twentieth century (New Orleans: History, 2000-2005).