|

Economic Plan

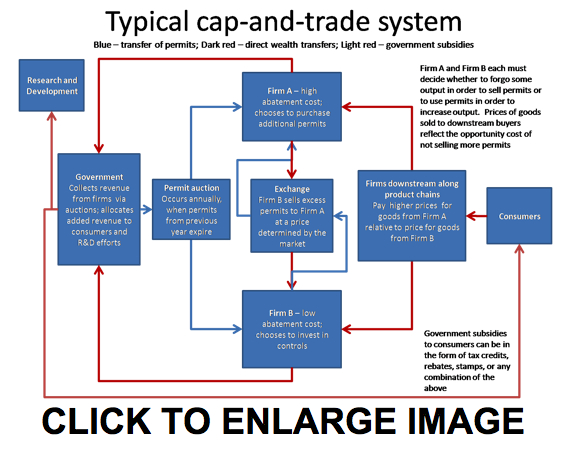

Child Pages Market-based approaches to sustainable management of water resources have the potential to reduce water use in water-stressed regions. In western North America, undervaluation of water has promoted excessive water consumption, so we propose the creation of a water market in which prices reflect the actual scarcity of water. Such a market structure will ensure that water reaches those who value it the most and that excess water use nonessential to human welfare is minimized. Economic incentives for water efficiency and conservation will enhance the effectiveness of sector-specific policies within our comprehensive plan for sustainable water management. While markets that price water based on scarcity may help with conservation efforts on a wide scale, a water market alone cannot fully address the environmental and social ramifications of excess water usage. In drafting our recommendations for sustainable water management policy, we strive for sensitivity towards the needs of low-income individuals who may be unable to afford water at higher prices. To mitigate the regressive nature of raising the price of water, our proposal will be revenue neutral; most of the revenue gained from raising water prices will be distributed to low-income individuals and other entities encountering financial difficulty due to higher water prices. The remaining funds will support means to enhance, broaden, and sustain the gains made in sustainable water management, including but not limited to efforts in scientific research and public awareness. Our economic plan for water management covers the US, Canada, and Mexico in their entirety, but since the environmental impacts of water stress tends to be local, we will tailor specific policy instruments within our wider policy framework towards managing water sustainably at local and regional levels. Upstream initiative: Cap-and-trade allowance framework for sustainable water managementOur proposal for a cap-and-trade system of water abstraction allowances is derived loosely from the water trading framework already in place in Australia as part of its National Water Initiative. A cap-and-trade system of water abstraction allowances, under which total volume of water withdrawn in a particular region may not exceed the total equivalent number of allowances issued for that region, will serve such purposes by reducing the total quantity of water withdrawn in a cost-effective manner. All water abstraction from any surface or subterranean hydrological system in Canada, and Mexico, and the United States on the continent of North America, excluding Puerto Rico and other overseas dependencies, will be under the jurisdiction of the cap-and-trade framework, which will take precedence over existing policies on water rights and markets unless such policies can be demonstrated to be compatible with the new policy. The cap-and-trade program will be administered federally under the North American Water Trading Authority [NAWTA] and implemented by NAWTA-affiliated regional committees in order to maintain responsiveness towards both region-specific concerns and inter-regional issues. Regions under the jurisdiction of these regional committees will be classified according to the body of water into which their watersheds ultimately drain, and all existing water authorities will have representation in their respective regional committees. Regional committees will be recognized as follows: Northeast Pacific, Interior Basins, Gulf and Caribbean, Atlantic and Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and Arctic. The regions are sub-divided into watershed zones each administered by a watershed commission as follows, as defined by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation of North America [CEC]: Atlantic Seaboard, Arctic Seaboard, Arkansas River, Caribbean, Colorado River, Columbia River, Gulf Seaboard, Hudson Seaboard, Interior Basins, Intermountain Basins North, Intermountain Basins South, Mackenzie River, Mississippi River, Missouri River, Nelson River, Ohio River, Pacific Seaboard, Rio Grande, Saint Lawrence River, and Yukon River. Although each commission will be a separate entity under NAWTA, they will be encouraged to collaborate on addressing water sustainability issues. Unless coinciding with natural watershed boundaries, political boundaries will not be used to determine the jurisdiction of commissions and committees administering the cap-and-trade program. Collaboration between the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States is discussed in detail within the section on resolving international issues. Prior to the launch of the cap-and-trade initiative, NAWTA along with other government agencies such as US Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA], US Department of the Interior [USDOI], and Environment Canada will monitor abstractions from watersheds and the watersheds' hydrological processes for three years starting in 2009. Data collected from the initial monitoring period, superseding ecological, hydrological, economic, and demographic data collected earlier, will be used in allocating allowances for the first five years of the cap-and-trade program. Monitoring will be conducted in collaboration with existing governmental and non-governmental agencies involved with statistical services and watershed management. Participation in the monitoring stages as well as the actual cap-and-trade system is mandatory for all firms withdrawing water from any watershed; firms include businesses, farms, municipalities, and all other entities physically withdrawing water directly from aquifers, springs, rivers, streams, lake, reservoir, or any other natural or artificial water body inland onwards from maritime mouths and estuaries of rivers. Firms not currently abstracting water but planning to do so must also participate in the cap-and-trade system. Non-participating firms will be ineligible for allowances and thus may not withdraw water. Exemptions from cap-and-trade will be granted for Native American reservations, up to an abstraction limit of 150 liters per capita per day, and public emergency services, with no abstraction limits whenever such limits impede their response ability. Fire departments, for instance, will not be subject to withdrawal caps when responding to emergencies. Allowances will be distributed via competitive auctions held by NAWTA at the beginning of each year. Auctions will consist of open bidding in which bid prices of any one firm are accessible to all participating firms; the highest-bidding firms will receive allowances up to the limit set during the monitoring period. As it will be mandated that auctions be conducted impartially with no regard to seniority, auctioning allowances will provide equal access to allowances for both existing firms and prospective entrants within each watershed zone, ensuring competitive pricing. All transfer payments from the firms to the government via the annual auctions will be appropriated for research and development work on water-use efficiency, restoration of ecosystems damaged by excessive abstraction or diversion of water, tax credits to encourage water-efficient design, and programs to reduce the impact of higher water prices upon households with income below the mean in the US. Income thresholds for compensation policies in Canada and Mexico will be determined by their governments. A limited portion of revenue from auctions may also be used to support additional efforts to limit potential negative impact on economic activity due to reform of water management praxis. As a measure of mitigating price volatility of allowances, derivatives trading in allowances involving futures, forwards, and options will be permitted, with trading limited to allowances valid for the current year of trade. These financial instruments will allow water suppliers to secure in advance of predicted water shortages allowances sold by other participants in the cap-and-trade system. A firm anticipating water scarcity due to possible drought can purchase allowances from other firms to be used during the drought period. If these allowances are acquired at lower prices than the spot price during the drought, the firm would be able to supply customers with water at rates lower than those based on spot prices for allowances. Futures and forwards are similar in principle except that futures are traded via an exchange or clearinghouse without prior specification of a buyer, as opposed to forwards which are sold over-the-counter directly between a buyer and a seller. Options confer upon the buyer a right to purchase a set quantity of allowances from a seller. Implementation of derivatives trading for the water abstraction allowance market, by allowing firms to make strategic decisions regarding the purchase and sale of allowances, will help reduce demand for unused allowances sold at spot prices during periods of water scarcity. Therefore, during such periods, water will be more affordable when participants in the cap-and-trade program can trade abstraction allowance backed derivatives. Each firm can withdraw as much water as their allowance holdings allow. A firm that withdraws less water than their allowable limit may sell its surplus allowances to other firms. Allowances can be traded between firms in the same major watershed and are valid only during their year of issue; unused allowances will retire one year after their respective dates of issue or at the date of conclusion of the subsequent year's auction, whichever date arrives earlier. If any firm wishes to exceed their initially-allocated annual abstraction limit, that particular firm will need to purchase additional allowances from firms holding surplus allowances. Each firm is entitled to the water that it abstracted, thus unless otherwise defined per local and regional mandates, water already withdrawn via allowances will be considered as property of the firm and not subject to regulation by NAWTA. Firms that exceed their abstraction limits without obtaining the necessary allowances will face fines triple the uncapped cost of allowances necessary to cover the firms' allowance deficit. Local and regional authorities also reserve the right to penalize firms whose excess withdrawals are demonstrated to be causing environmental harm; these penalties will be levied in addition to the treble fines intended to deter withdrawals beyond allowance limits. After the first year of the cap-and-trade program, the system-wide cap on water abstraction will decrease by two percent. Subsequent decreases of the cap will occur annually at a rate of two percent on the previous year's cap for five years following program launch. Annual percent decreases in total allowances available would not account for aggregate withdrawals at a per-capita rate of 100 L/day unless specified otherwise due to regional and/or ecological factors and constraints. For example, a region with per capita water abstraction of 1,000 L/day need only be concerned with reducing to a more sustainable level the 900 L/capita/day level that exceeds the 100 L/capita/day threshold. Caps on abstraction from specific watersheds may be placed and/or adjusted based on ecological and hydrological factors necessitating a more-rapid rate of reduction of water withdrawals. Chronic drought conditions in which ecosystems suffer prolonged stress due to reduced water flow in rivers, for instance, may provide sufficient justification for accelerating the annual rate of reduction in water abstraction for the affected region. Decreases in cap levels for specific watersheds will proceed until attainment of an ecologically sustainable rate of water abstraction, after which the cap will either be lowered further to enable recovery of the watershed or be set at the maximum sustainable levels. At the end of the first five-year period and every five years thereafter, NAWTA in conjunction with other governmental and non-governmental organizations will conduct a comprehensive review of the cap-and-trade system and the state of water resources, particularly any changes that occurred since the initial monitoring period. Information collected during the interim review periods will be used to determine the need for and degree of adjustments to annual abstraction targets over the following five years. If aggregate above-threshold water abstraction decreases at a rate faster than the annual decreases in caps, the annual decreases in caps may be accelerated in order to promote sustainability without incurring considerable additional costs. During periods of drought, NAWTA will reserve the right to place temporary caps on water withdrawals in affected watersheds in order to maintain the watersheds' ecological integrity. Case scenario: Application of cap-and-trade to the Ogallala AquiferTo achieve sustainability of water abstraction from the Ogallala Aquifer, a cap on total water withdrawals will be established at a level equivalent to the present overdraft rate, or rate of groundwater mining, of 79.864 mm/year or lower should overdraft rates decline prior to the first auction of allowances. Monitoring of water withdrawals for two to four years prior to initiation of the cap will allow the federal government to determine allotment of permits. Initially, the cap level will decrease by 1.0973 mm equivalent each year assuming a first-year cap at 79.864 mm/year equivalent, with a 50-year target of reducing overdraft to 25 mm/year, which equals the current estimated recharge rate, or lower. In the context of heavy agricultural intensity in the High Plains region, such reductions will be attainable via water conservation and efficiency measures including but not limited to cultivating less-water-intensive crops, increasing efficiency of irrigation systems, and scheduling irrigation in ways that minimize evaporative water loss. After the first 50 years of program implementation, the quantity of available allowances may be decreased further to allow net recharging of the aquifer; such a decision will take into account the marginal costs of further reductions in water abstraction. A comprehensive review of the cap-and-trade system's performance as well as hydrological trends in the aquifer will occur every five years, after which the rate of decrease in upper withdrawal limits will be adjusted according to best-available data on the physical state of the aquifer. As is the case with the rest of the cap-and-trade initiative, no withdrawals from any particular source may exceed the first cap level set for that intake point. Monetary penalties for drilling unauthorized wells in the Ogallala aquifer service region or any other aquifer service region will be triple the first-year cost of monitoring the well. Additional fines from withdrawing water from unauthorized wells will follow the same structure as fines for all unauthorized withdraws, at a rate triple the market price of water including uncapped allowance prices. Conforming to all other policies on noncompliance with cap-and-trade directives, local and regional authorities will reserve the right to levy additional penalties on contravening parties. More detailed information on managing groundwater and agricultural water use can be found in their respective sections on solutions. Appropriation of revenue from upstream cap-and-trade planRevenues from the first auction of the cap-and-trade initiative are estimated to range from 528 billion USD to 2.352 trillion 2007 USD. These aggregate amounts include only the revenues to be received by the federal government of the United States; the government of Canada and the government of the United Mexican States will receive cap-and-trade auction revenues in separate accounts. An annual abstraction rate of 1,680 cubic meters per capita is used as the baseline for calculating projected revenues (OECD, 2008, p. 23). Figures for the lower bound are based on a price floor for water that utilizes an allowance price of 1 USD per cubic meter in addition to the price of purified effluent water delivered via mains. Figures for the upper bound are based on a price ceiling for water such that the average residential end-user in each state will spend five percent of his or her income on supplied water assuming that he or she maintains current levels of consumption after the cap-and-trade program goes into effect. Supplied water does not include water withdrawn directly from sources, including but not limited to water directly withdrawn for irrigation, industrial cooling, or resource extraction. Future revenue streams will vary depending on demographic changes, economic trends, commercial readiness of technologies that help conserve water, and more generally the supply and demand for allowances. NAWTA, with consultation with relevant governmental agencies and non-governmental organizations, will reserve the authority to determine exact allocation of revenues. Appropriation of revenue will not be conducted in such a way that favors certain constituencies to the detriment of others. Funds from each annual auction will be classified and distributed accordingly into fixed and variable streams. Fixed streams, consisting of funds set at a defined quantity each year regardless of total revenues from the auctions, will be appropriated for supporting research and development, guaranteeing water for Native American reservations, and covering expenses from public awareness campaigns. Appropriations for the aforementioned initiatives during the first year of cap-and-trade will be set at 14 billion, 1.8 billion, and 200 million 2007 USD, respectively. Due to the negative impact of higher water prices for low-income individuals, the remaining revenue, classified under variable streams since the exact appropriations depend on total auction revenue generated, will be dispensed to low-income households and small businesses to compensate for higher water costs. The distribution ratio of relief between households and small businesses will be four to one under the first cap. All appropriations for subsequent years under the cap-and-trade allowance system will be subject to revision based on input from the affected parties and regulatory authorities. Downstream initiativesTo ensure that water is affordable for all, we plan on implementing a schedule of progressive block pricing of water for household consumption. This schedule, administered by NAWTA on the federal level respective to Canada, Mexico, and the US, sets a threshold of 100 L/capita/day for use of water charged at a rate below market rates as determined by allowance prices. This means that an individual can buy up to 100 L of water per day at a price equal to the cost of treated municipal wastewater. We chose 100 L/capita/day based on comparable European levels of water consumption and twice the 50 L/capita/day limit proposed by Gleick (1999, as cited in Hanemann, 2006, p. 79). In Spain, for example, water consumption by households and small businesses in 2004 varied between 100 and 150 L/capita/day, with rates of 119, 121, 124, and 137 L/capita/day for Barcelona, Valencia, Madrid, and Sevillia respectively (IWA, 2006, p. 8). Per-capita water withdrawal from public supplies in the United States as of 2000, the most recent year for which comparable figures are available, is 677.07 L/capita/day (USGS). This number is based on the United States Geological Survey's public supply water withdrawal numbers from 2000, for which public supplies are classified as water received from public or private distributors serving 25 or more users or operating 15 or more connections. We estimate the price of water below the 100 L/capita/day threshold to be 0.72 USD/cubic meter should the cap-and-trade system go into effect at present; average current water price for US households is 0.528 USD/cubic meter (USEPA, 2003, p. 11). We chose to price water based on the price of treated wastewater so that sewage treatment plants can recover their costs of treating wastewater, excluding delivery and distribution costs. This will encourage the use of treated effluent water. In places where treated effluent water is not used, the revenue from the difference in price of water and cost of supplying water will be re-circulated into the economy in the form of programs for alleviating the burden on low-income consumers and small businesses. The difference between the floor price and the price the water distributor receives for water not supplied by treated wastewater effectively serves as a tax to discourage excess water consumption. On the other hand, no wastewater treatment plant owner or operator will be forced to reduce water rates below the floor rate since the resulting profits create incentives for improving water supply service. The threshold of 100 L/capita/day ensures that water remains affordable for all. Excess water use will be charged at significantly higher rates than use below the threshold. All water bought by a person that is above their 100 L/day allotment is sold at market price that is allowed to fluctuate between a floor price of 1.72 USD/cubic meter, which is the sum of the 1USD/cubic meter allowance price floor and the price of treated effluent water, and a ceiling price of 5.17 USD/cubic meter, determined such that the current level of individual water consumption costs five percent of US mean per-capita income. Ceiling prices will not apply to discretionary usage unrelated to the production of essential goods and services including but not limited to food crops and electric power; discretionary water usage that would not qualify for ceiling prices include residential consumption above 200 L/capita/day, roughly three-quarters of the per capita water abstraction rate in Spain as of 2005. In addition, residential water consumption above 200 L/capita/day will be subject to a price floor of 3.72 USD/cubic meter. All ceiling and floor prices are indexed to inflation, with figures quoted in 2007 USD, and, if sold in Canada or Mexico, adjusted for discrepancies in per-capita income by multiplying the price by the ratio of nominal income to purchasing power parity income. Transport, distribution, and delivery [TD&D] costs are not included in the price figures and thus will apply as additional costs based on cost of TD&D infrastructure and distance the delivered water traveled between its source and end-use. We understand that even with the 100L/capita/day threshold water may not be affordable for all. For this reason, we also plan on implementing programs for alleviating the financial burden on low-income consumers and small businesses. These programs include a voluntary water stamp program similar to the currently implemented food stamp program. Eligibility for the water stamp program will be based on gross and net income, analogous to the food stamp system (South Dakota Department of Social Services). In addition, we plan on implementing income tax rebates independent of the recipients' water use. The money from these tax rebates will come from the permit auctions preformed at the beginning of each year. Households making less money than the mean household income will be eligible to receive incremental tax rebates based on current tax brackets. Any consumer eligible for the water stamp program may elect to receive the monetary equivalent of all or a portion of water stamps as a lump sum rebate in addition to other rebates for which he or she may be eligible. Applying the floor price of allowances to the entire cap-and-trade system, the average individual in households earning below the mean US household income line can expect to receive rebates worth 2,000 USD at 2007 currency values, which may fluctuate based on the price of allowances and auction revenue collected. Individuals will receive rebates of relatively greater monetary value in years of relatively higher auction prices for allowances. We believe that everyone has the right to access safe and reliable water. With the changes laid out above, we aim to ensure that water is available to all. The progressive block pricing of water for household consumption ensures that enough water to survive on is made affordable to all consumers, who will ideally through conservation and efficiency measures experience a decrease in total spending on water even as unit prices of water increase. Via public awareness campaigns, households and businesses will discover that they can potentially be paying less for total water use in the long term under our plan; this point is crucial towards gaining widespread public support. Water stamps and tax rebates are also part of our plan as safeguards to alleviate the financial burden on low-income consumers and small businesses. For economically disadvantaged households viewing the increase in water prices as equivalent to a tax increase, our rebate system effectively reduces income tax and therefore offsets the impact of increased water prices on individual purchasing power. With these changes, water will remain affordable under price-based conservation incentives. Decoupling of water utility revenues from quantity of water deliveredEven if consumers may benefit from lower water bills in conjunction with higher water rates, our economic plan will be more effective with active support from water utilities. Utilities will not be able to benefit from our plan if utilities continue to find increasing water deliveries to customers beneficial towards revenue and profit maximization. To accelerate water conservation efforts, water utilities need economic and financial incentives to encourage the adoption of water-efficient practices among their customers. We propose that federal, regional, and local regulatory authorities decouple water utilities' revenue streams from the quantity of water they deliver. Decoupling is already being proposed and under way in the electric utilities sector, and we are seeking to incorporate a similar decoupled rate structure to the water utilities sector. Under a decoupled rate structure, a water utility will have incentive to assist its customers trying to conserve water since doing so improves profitability, and both the utility and its customers benefit from receiving a share of savings from avoided spending on water (due to more efficient use) and avoided cost of expanded delivery infrastructure. The utility will also be able to increase water rates, spurring additional conservation efforts in turn and lessening any rebound effect in which customers use more water as efficiency increases. On the other hand, the utility may not cover the cost of expanding water delivery infrastructure via rate increases. When consumption of water increases, utilities will forfeit to the regulatory authorities a portion of revenue generated from increased water delivery such that the additional units of water sold incur losses. In such cases, the utility can increase its profitability by encouraging water conservation among its customers; for utilities operating on a basis of decoupled revenue streams, water saved through conservation can be viewed as capacity additions more cost-effective than adding capacity via expansion of water delivery infrastructure. Decoupling will therefore enable water utilities to promote conservation while reaping financial benefits, complementing existing and proposed efforts at reducing water use to environmentally sustainable levels. Re-appropriation of subsidies towards sustainable water managementAll subsidies that currently promote unsustainable water consumption will be replaced with subsidies that encourage adoption of environmentally sustainable water management. The Congressional Budget Office [CBO] (2008) projected that agricultural subsidies from 2009 to 2018 will total 160.7 billion USD in budget outlays (Table 1.4). We recommend that production subsidies for water-intensive field crops such as corn and soya be shifted towards helping farmers offset the cost of purchasing water-efficient irrigation equipment and shifting production towards less-water-intensive crops. In addition, open space development, including but not limited to extension of roads, power lines, sewerage pipes, and other infrastructure onto undeveloped land, will no longer be subsidized by tax revenues. Coupled with the rise in water rates under the cap-and-trade system, non-subsidization of low-density suburban development will reduce water intensity due to population pressures. Low-density residential development is significantly more water-intensive than slightly denser development as measured in households per residential acre. For example, increasing residential density from 3 households per residential acre, typical of low-density detached suburban housing, to 10 households per residential acre, typical of low-density neighborhoods consisting of row houses and townhouses, reduces household water consumption by three-fifths (Sierra Club). More details on population growth and agricultural practices are discussed under their respective sections of this report. Urban growth boundaries [UGBs] to control water-intensive open space development, complementing the elimination of subsidies that enable such development, are outside the scope of the economic plan and best devised and implemented at local and regional levels, but the option of federal intervention is discussed as a contingency measure. We acknowledge that our market-based initiatives to promote sustainable water management may cause economic disruption immediately after implementation. Olmstead and Stavins (2007) cited that price elasticity of demand for water, expressed here as absolute values, is less than one in the short run, which means that initially, consumers can expect to pay more for water (pp. 21-25). However, after the initial stages of our plan, we expect individuals and businesses to have adjusted their practices to reflect the new economics of water supply, conservation, and efficiency, so therefore water costs for consumers may potentially decrease in the long term. Lack of economic incentives for water sustainability will diminish the effectiveness of our sector-specific policy proposals. For example, deploying water-conserving technology while water remains undervalued may cause consumers to use more water since water costs less per unit. If our policies on groundwater, water reuse, and sustainable agriculture fail due to lack of proper incentives, further deepening of the water crisis may warrant drastic contingency measures that may prove more disruptive socially and economically than what we propose currently. Above all, we stress that the revenue-neutrality of our market-based initiatives will mitigate potential negative ramifications for economic welfare in North America. Downloadable spreadsheets: Cash flow and levelized costs for generic sewage treatment plants Water price estimation with revenue projections under the cap-and-trade system |

|