| Vol.

XXII No.

3 January / February 2010 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

The Demand for MIT Graduates

MIT’s Class of 2009 graduated during one of the worst job markets in recent history. Recent college graduates across the nation struggled in this economic climate, as evidenced by the fact that only 20% of 2009 college graduates had full-time employment (compared to 51% for the same period in 2007), rising to 60% within six months of graduation (National Association of Colleges and Employers). Companies recruiting on-campus fell by 40% or more, even at MIT.

Despite this bleak backdrop, the MIT Class of 2009 bucked the trends by faring better than the national average in nearly all employment measures. Informal discussions among our peer institutions indicate that our graduates also fared far better than their peers at other Ivy+ schools.

Although MIT’s recent graduates may have done better in the job market than most of their peers, they definitely experienced the impact of the recession with a decline in the number who found jobs and lower salaries for some degree levels. The most significant declines were among Master’s and Doctoral degree recipients, but the lack of comprehensive national data for Master’s and Doctoral graduates makes it difficult to determine how their outcomes compare with their national peers.

How do we account for this performance and how has it changed over time? Employers of our new graduates report that they highly value the unique combination of strengths that MIT graduates possess, in particular, an unusual level of creativity combined with analytical and problem-solving skills. We also know that the technology sectors did not experience as much of a hiring downturn as other areas, which certainly plays to our strengths. We will explore this further by reviewing responses from the 2009 MIT Graduating Student Survey as well as the new Doctoral Student Exit Survey and looking at trend data for the last three to five years.

In looking ahead, national data indicate that hiring will continue to slide, with 39.7% of employers reporting that they expect to decrease their college hiring in 2010. However, the national data does provide some bright spots for MIT, with demand for engineering and information sciences/systems majors topping the lists for all degree levels. Additionally, the Global Education and Career Development Center (GECDC) has seen an increase in on-campus recruiting over last year, with 6.5% more interviews conducted over fall 2008. Finally, numerous employers have indicated that they have continued to view MIT as a top-recruiting target, even as they’ve pared down the number of the schools at which they recruit.

Student experiences while at MIT play a significant role in their success. Nationally, employers report that in deciding between two equally qualified candidates, they will select the one who has held a leadership position. The same report indicates that internship, extracurricular, and volunteer activities can be a factor and, for the first time, GECDC had companies specifically targeting and hiring students because of participation in a study abroad experience.

(click on image to enlarge)

Figure 2 – Average Starting Salary of Graduating MIT Students

(click on image to enlarge)

| Back to top |

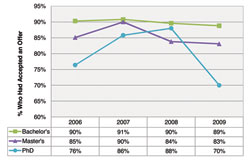

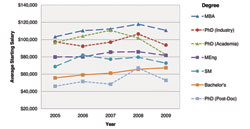

SB Graduates Fared Well in the Shrinking Job Market

Despite the challenging job market in 2009, 89% of MIT SB graduates who were pursuing work had accepted a job offer by the time of graduation. This was enormously higher than the national placement rate of 20% for all 2009 graduates and was only 1% lower than the previous year [see Figure 1]. At the same time, while MIT Master’s and PhD graduates saw a decrease in starting salaries, our SB graduates saw a 2.5% increase to $67,270 which continues a five-year upward trend [see Figure 2]. This was significantly higher than the national average for all disciplines, $48,633, as well as for engineering graduates, $59,670.

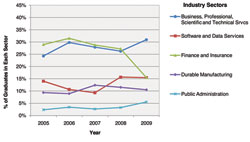

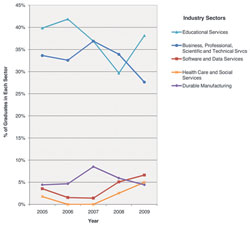

Finance was replaced by management consulting and technology as the top hiring industry sectors of SB graduates [see Figure 3]. In 2007, Morgan Stanley, Lehman Brothers, JP Morgan, and Goldman Sachs were among the top 10 employers of MIT graduates. Only Morgan Stanley remained in the top 10 by 2009, and was part of a diverse mix of top employers of MIT graduates, including MIT, McKinsey & Co., Microsoft, Exxon Mobil, Booz Allen Hamilton, Merck, Oracle, and Intel. Lincoln Labs and various other campus laboratories accounted for most of the hires within MIT.

The decrease in on-campus recruiting by employers resulted in fewer job applications and fewer interviews for SB graduates than in previous years. However, on-campus recruiting continued as the primary source of employment. At the same time, it is clear that MIT students were resourceful in this challenging job market. They continued to use networking as a key source of employment and relied more heavily on developing opportunities through internships, career fairs, and contacts acquired through the GECDC. The ultimate outcome was an increase in the average number of offers.

Learning Outside the Classroom Key to Career Preparation

In the 2008 Senior Survey, 83% of students indicated that MIT prepared them generally well or very well for the job market. While academic experiences provide the cornerstone in developing the quantitative and analytical skills of MIT graduates that are highly sought by employers, learning outside the classroom helps students experience diverse environments and perspectives, broaden their communications skills, and develop a better sense of themselves and possible career trajectories. Communication skills are perennially ranked as the most important candidate skill for new graduate hires.

An internship can be a very impactful learning experience for students, as they are working to solve real-world challenges in industry and academia. Undergraduate participation in internships has steadily grown in recent years. In 2009, 78% of SB graduates had participated in an internship, up from 72% in 2006, 75% in 2007, and 77% in 2008. The primary sources of internships include UPOP, externships, career fairs, departmental internships, and MISTI. These hands-on experiences expose students to different ways of thinking and solving problems. Students broaden their technical skills and develop business skills while developing a network of valuable contacts.

Students who choose to participate in an internship abroad not only learn through work experience, but also gain critical global competencies that are valued by employers. Through internships, research, public service, and study abroad, more and more students are participating in an educational experience abroad. In 2009, 30% of SB graduates indicated they had a global educational experience, which is up sharply from 24% in 2008.

MIT is working to make a global experience an essential part of an MIT education. One key aspect of this sustained effort has been to provide more global educational opportunities for students through the creation of the Global Education Office and the expansion of key programs such as International Research Opportunities Program (IROP), D-Lab, MISTI, and public service abroad. While increasing the number of opportunities, MIT is also working to eliminate the barriers that have limited student participation. For example, the financial aid budget is now adjusted upwards for students studying abroad in locations where the cost of living is higher than at MIT. Also, students who lived on campus prior to an Institute-approved program abroad are now guaranteed on-campus housing upon their return. Finally, some initial discussions with departments are underway relative to transfer credit from foreign universities and course pathways that could guide students in preparation for study abroad.

Through learning opportunities outside the classroom, students develop relational and collaborative abilities that are key to leadership development. Employers are interested in students who have demonstrated the ability to lead and collaborate. In 2009, 71% of SB graduates indicated that they participated in leadership activities, up significantly from 64% the previous year. MIT continues to broaden the portfolio of opportunities for formal leadership training. For example, the recently initiated Gordon-MIT Engineering Leadership Program focuses on developing next-generation technical leaders who are able to understand and address significant engineering problems in real-world situations.

These trends suggest that the rigorous, technically grounded education at MIT is serving our students well. The demand clearly indicates that the complementary experiences outside the classroom are critical to this global market acceptance. MIT can be proud of this and we will continue to offer and improve this excellent education.

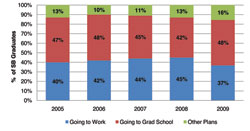

More SB Graduates Go to Graduate School

While job placement remained strong in 2009, there was an increase in the number of SB graduates pursuing graduate school, specifically Master’s programs. This may be a temporary reflection of the state of the economy in which students are putting off entering the job market [see Figure 4]. Of the SB graduates who went on to graduate school, 36% are pursuing a PhD, 22% MEng, 20% MS, and 14% MD. Top graduate schools attended by SB graduates included MIT, Stanford, Harvard, UC Berkeley, Cal Tech, and UC San Diego. MIT continues to dominate as the top choice for graduate school. 66% of SB graduates pursing graduate school applied to MIT and 43% are now attending MIT. Stanford is the second choice, where 7% are attending.

Of the students pursuing graduate school, 69 SB graduates applied to medical school, representing an increase of 15% over 2008. This cohort had the highest acceptance rate in recent history, with 94% accepted into medical school, a jump of 8% over 2008. The national acceptance rate was 46% for all medical school applicants, regardless of degree of level.

In their roles as UROP supervisors and academic advisors, faculty can have a major impact on a student’s decision to attend graduate school as well as the graduate school selection process. 68% of SB graduates going to graduate school indicated that faculty had provided assistance in their search for a graduate program; 53% had received assistance specifically from their faculty advisor. At the same time, there is also a direct correlation between UROP participation and graduate school. Historically, 51% of students with UROP experience pursue graduate school while only 40% without UROP experience do so. An impressive 86% of 2009 SB graduates completed a UROP.

(click on image to enlarge)

Master’s Graduates Accepted Lower Salary Offers

For 2009 Master’s graduates who were pursuing work, the 83% job placement rate was down by only 1% from the previous year [see Figure 1]. While they were successful in finding jobs, MBA, MEng, and SM graduates experienced the first decrease in starting salaries in at least five years. The average for MBAs was $110,713, down 6.5% from the previous year, the average for MEng graduates was $81,900, down 4.8%, and the average for SM graduates was $73,966, down 7.6% [see Figure 2].

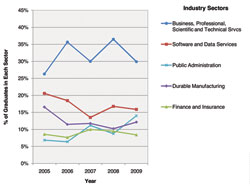

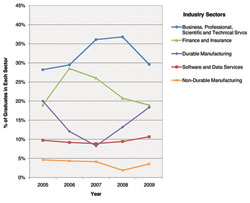

While management consulting, scientific services, and technology remained as the top hiring industry sectors of SM and MEng graduates, fewer graduates were hired than in past years [see Figure 5]. Similarly for MBAs, management consulting, scientific services, and finance continued to hire the most graduates, but at a decreased level [see Figure 6]. Alternately, more Master’s graduates went into public administration, manufacturing, transportation, and a multitude of diverse sectors that did not traditionally hire at MIT. The shift into these industries, which do not typically have high entry-level salaries, could explain the decrease in starting salaries. Top employers included Apple, Bain, Cisco, McKinsey & Co., Microsoft, U.S. Air Force, Intel, Google, and Fidelity Investments.

As sources of prospective employment became scarcer, Master’s graduates faced a more competitive job search than in previous years, resulting in students applying to more jobs than ever before. The average number of applications went from nine in 2008 to 13 in 2009. Career fairs, applying directly to employers, and departmental contacts were less fruitful as job sources. Instead, more applied to and found jobs through on-campus recruiting. There may have been fewer employers on campus, but 42% of SM graduates were able to find jobs in this way, up from 38% the previous year.

Internships also became a more significant source of jobs; 20% accepted offers from their internship employers which was a dramatic jump from 15% in 2008. Part of this could be attributed to the significant increase in the number of Master’s graduates who participated in an internship, 63% in 2009, up from 51% in 2008. Similar to undergraduates, Master’s students are recognizing that internships provide a valuable vehicle for personal, intellectual, and career development. Most relied on their department, GECDC’s on-campus recruiting, and the Leaders for Global Operations programs as their internship source.

As future global leaders, more Master’s graduates included a global educational experience during their tenure at MIT. Participation has steadily increased from 30% in 2006 to 41% in 2009. Sloan’s Global Entrepreneurship Lab (G-Lab) provided the greatest number of opportunities by giving over 100 students a consulting and internship experience abroad. Beyond G-Lab, Master’s graduates primarily sought out international internships and international development projects.

| Back to top |

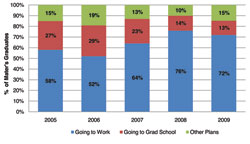

Fewer Master’s Graduates Immediately Pursue Graduate School

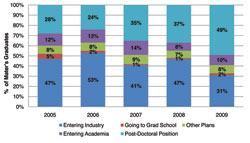

Unlike undergraduates, the number of Master’s graduates pursuing additional graduate studies has steadily declined over the past five years, from 27% in 2005 to 13% in 2009 [see Figure 7]. Top graduate school destinations for Master’s graduates included MIT, Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford, with MIT by far the top choice. 82% of Master’s graduates pursing graduate school applied to MIT and 64% are now attending.

The trends outlined here show that a Master’s degree is still valuable even if the market value, measured by starting salaries, has dropped in the last year. The data also show the growing value of internships as part of the Master’s experience. We will continue to evolve our programs in light of these needs.

(click on image to enlarge)

PhD Graduates Felt the Pain of the Economic Downturn

A soft academic job market and the overall decline of the job market had a major impact on the ability of PhD graduates to find employment. On average, PhD graduates had fewer interviews than last year, four versus six, and the average number of offers declined from three to two. Only 70% had accepted a job by graduation, a dramatic decrease from 88% in 2008 [see Figure 1]. The effect on salaries was no less dramatic. Average starting salaries for PhDs entering a post-doctoral position were down 21% from the previous year to $52,737; for PhDs entering academia, salaries were down 19% to $82,422; and for PhDs entering industry, salaries were down 12% to $93,595 [see Figure 2].

While overall hiring was down, academia regained the position of top hiring industry sector for PhDs after a sharp drop in 2008. Beyond academia, more than a quarter of PhDs took positions in management consulting and scientific services [see Figure 8].

These sectors dominate hiring of PhDs. When combined, they hired 66% of all graduating PhDs. The top employers included MIT, Stanford, Harvard, McKinsey & Co., Cornell, and MGH.

More PhDs Pursue Post-Doc Positions

While 47% of PhD graduates intended to pursue a career in academia, only 10% planned to do so upon graduation. Alternately, 49% of PhDs planned to pursue a post-doctoral position as their first job. This represented a 24% increase over 2008 [see Figure 9]. This considerable rise was another reflection of the problematic PhD job market. More PhDs saw a post-doc as an intermediate position until the job market improves. The shortage of job opportunities also affected how PhDs perceived their career choices. 71% said they expect to take a job directly related to their graduate training, down dramatically from the prior three years: 93% in 2006, 90% in 2007, and 89% in 2008.

(click on image to enlarge)

Faculty Play a Strong Role in Shaping PhD Career Choices

Faculty occupy a central role in shaping and influencing a PhD student’s professional development, career path, and job search. 57% of PhD graduates strongly agreed that their dissertation/thesis advisors promoted their professional development. However, PhDs indicated that they are not consistently supported in making career choices outside of academia. 27% of PhD graduates reported being given little or no guidance about multiple career paths. Anecdotally, the GECDC reports students expressing concern about sharing plans to seek jobs in industry or in other non-academic areas with faculty and advisors. Despite what seems to be a bias towards academic careers, 55% felt their advisors would strongly support them in any career path. At the same time, 65% had received some direct assistance from their advisors in their employment search. In fact, in 2009, 26% of PhDs found jobs through a faculty contact. This was higher than in previous years and represents one of the top three vehicles through which PhD graduates found a job.

Consistent with SB and Master’s graduates, the learning experiences of PhDs in the classroom, lab, and outside the classroom are key elements in their career preparation. 80% of PhD graduates had been a teaching assistant (TA) at MIT and 85% felt the experience was helpful to their professional development. 91% of PhD graduates had been a research assistant (RA) at MIT and 91% felt the experience was helpful to their professional development. At the same time, internships have become important to a larger number of PhD students as they recogninze the value of balancing their research with applied experience in industry and at other research facilities. In 2009, participation in internships rose to 27% from 24% the previous year and represents a steady increase. More PhDs are also participating in leadership activities during their graduate program. Participation increased to 48% from 40% the previous year.

Overall, the analysis and data in this article shows that MIT degrees are highly valued and that we can be proud of what we produce in our students. MIT must continue to examine all its degrees and modify them in response to fundamental pedagogical advances, new knowledge, and market demand.

Sources

Each year the Office of Institutional Research, in conjunction with the Global Education and Career Development Center (GECDC), surveys graduates to determine employment or continuing education status, salary information, satisfaction with career and global education services, and perspectives on various aspects of their MIT experience. This year, questions regarding PhD post-graduation employment and salary were incorporated into the Doctoral Student Exit Survey. The results of each survey can be found at web.mit.edu/career/www/infostats/graduation.html and web.mit.edu/ir/surveys/grad.html.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |